Computing may be fundamental to life, intelligence, and everything, but its history is tortuous, full of false starts and misunderstandings. To better understand our conceptions and misconceptions about computing, we’ll need to begin well before Turing and von Neumann, connecting their work to its roots in mathematics, industrial engineering, and neuroscience. We’ll also need to take stock of the social context surrounding its development.

This will be a short and curated, rather than definitive or comprehensive, account. Its goal is to reassess our received wisdom about what computing is (or isn’t), and its relationship to brains and minds, labor, intelligence, and “rationality.”

Our prehistory of computing begins 1 during the European Enlightenment, with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), the co-inventor of calculus, among many other achievements. His “stepped reckoning machine” was the first mechanical calculator that could perform all four basic arithmetic operations, but this was only a baby step in his far more ambitious agenda. 2

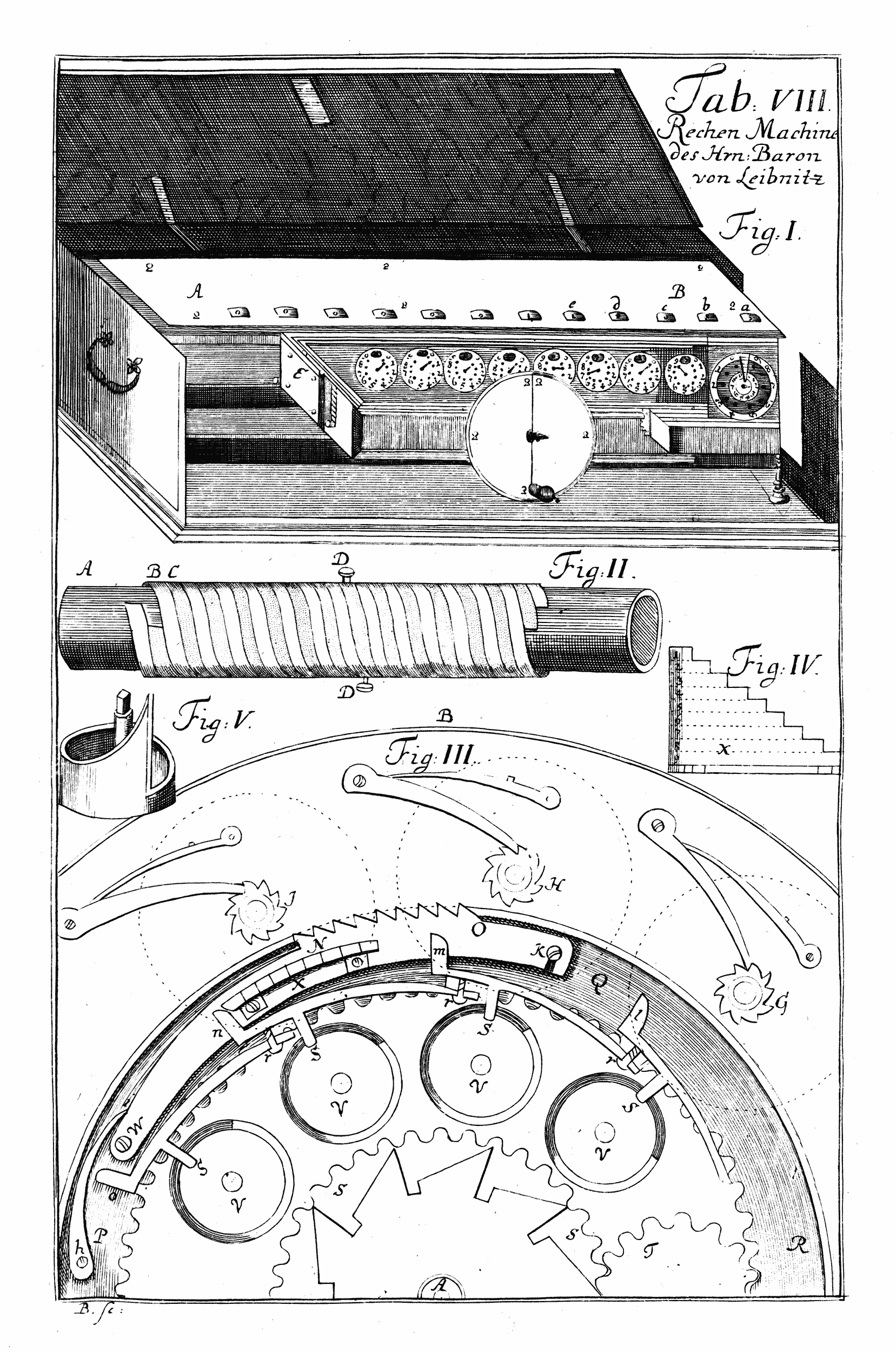

Posthumous diagram of Leibniz’s stepped reckoner, from Leupold 1727

At age twenty, Leibniz asserted that one day, we’d be able to formulate and answer any question—not just in math, but in politics, economics, philosophy, even in ethics or religion—using pure logic: “If controversies were to arise, there would be no more need of disputation between two philosophers than between two accountants. For it would suffice to take their pencils in their hands, to sit down with their slates and say to each other […]: Let us calculate [calculemus].” 3

In imagining that accountants—human computers, really—could work out the right answer to any question once properly formulated, Leibniz presumed the existence of universal truth, both factual and normative: a Platonic world of pure, timeless, and axiomatically correct ideas. He only needed to devise—or discover—a formal language for expressing any proposition symbolically (he called this a characteristica universalis, or “universal notation”), and an algebra for manipulating such propositions (a calculus ratiocinator or “calculus for reasoning”). 4 The existence of God, the right of the Habsburgs to rule Austria, and the legitimacy of same-sex marriage could all boil down to logical proofs, just like the value of pi. And, if so, a descendant of the reckoning machine could eventually compute such proofs mechanically.

This grand idea died a slow death over centuries, though, in a sense, the entire field of computer science grew out of its moldering remains, like a sapling out of a nurse log. Remember that the theoretical foundations of computing were laid by Turing in his attempt to solve the Entscheidungsproblem in the 1930s—the problem of finding a general algorithm for deciding on the truth value of a mathematical statement. 5 This was Leibniz’s problem, albeit restricted to math. The bad news: even in that purely abstract, formal domain, Turing proved that no such algorithm existed. The good news: in the process, he invented (or discovered) universal computation.

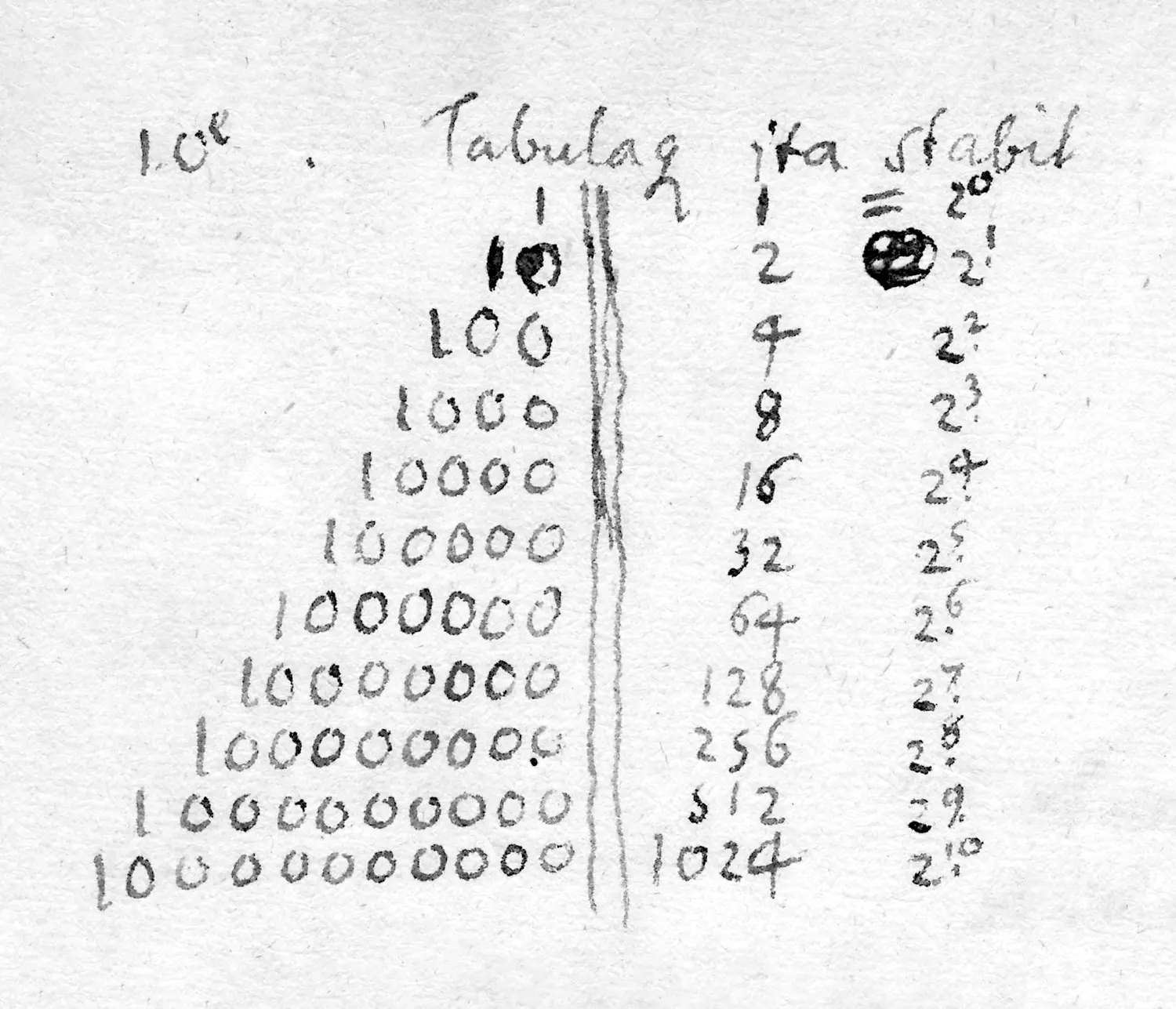

From a Leibniz manuscript, around 1703

Although Leibniz worked on many other problems throughout his long career, he never gave up on the quest for a universal symbolic language. It was his Holy Grail. In a New Year’s letter to the Duke of Brunswick in 1697, Leibniz excitedly explained some progress toward this goal: numbers could be represented in binary, using only the digits 0 and 1. 6 The letter sketched a design for a medallion to commemorate this insight featuring an image of divine creation, noting that it would be “difficult to find a better illustration of this secret in nature or philosophy […] that God made everything from nothing.”

Design for a medallion by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1697 to commemorate binary notation, depicting an imago creationis (“image of creation”), a table of binary numbers from zero to sixteen, and the mottoes unum autem necessarium (“the one is necessary”) and unus ex nihilo omnia (“the one from nothing makes all things”).

Because it was both a minimal representation for numbers and a natural notation for yes/no logic, binary seemed the obvious basis for Leibniz’s characteristica universalis. George Boole (1815–1864), the self-taught nineteenth-century mathematician who formalized the Boolean logic at the heart of virtually all digital computing, independently arrived at the same conclusion more than a century later. 7

Silly ancien régime hairstyles

Gaspard de Prony

In practice, though, the earliest “human computers” didn’t use any special notation or work out the answers to weighty questions on slates; in short, they didn’t resemble Leibniz’s philosopher-accountants. They were out-of-work hairdressers employed by a civil engineer, Gaspard de Prony (1755–1839), to crank out books of logarithmic and trigonometric function tables for land surveyors to use after the French Revolution. 8 (The hairdressers were out of work because many of their former customers, Ancien Régime aristocrats, were losing their towering hairdos, along with their heads, to the guillotine. Survivors, rich and poor alike, were wisely opting to keep their hair short and plain. 9 ) These hairdressers may not have known higher math, but they were used to working carefully and methodically. They had no trouble performing the elementary operations into which each calculation had been decomposed: addition and subtraction. 10

Prony framed his project in industrial terms, boasting that division of labor allowed him to “manufacture logarithms as easily as one manufactures pins.” The reference to pin manufacture came straight out of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, the founding document of industrial capitalism. 11 Leibniz had complained that “it is beneath the dignity of excellent men to waste their time in calculation when any peasant could do the work just as accurately with the aid of a machine.” 12 Although Prony’s hairdressers were not (yet) using machines, they were organized to work like one. 13 And, of course, machines had already been invented for adding and subtracting.

.webp)

Engraving of a pin factory from Diderot and d’Alembert 1762, a classic illustration of the division of labor

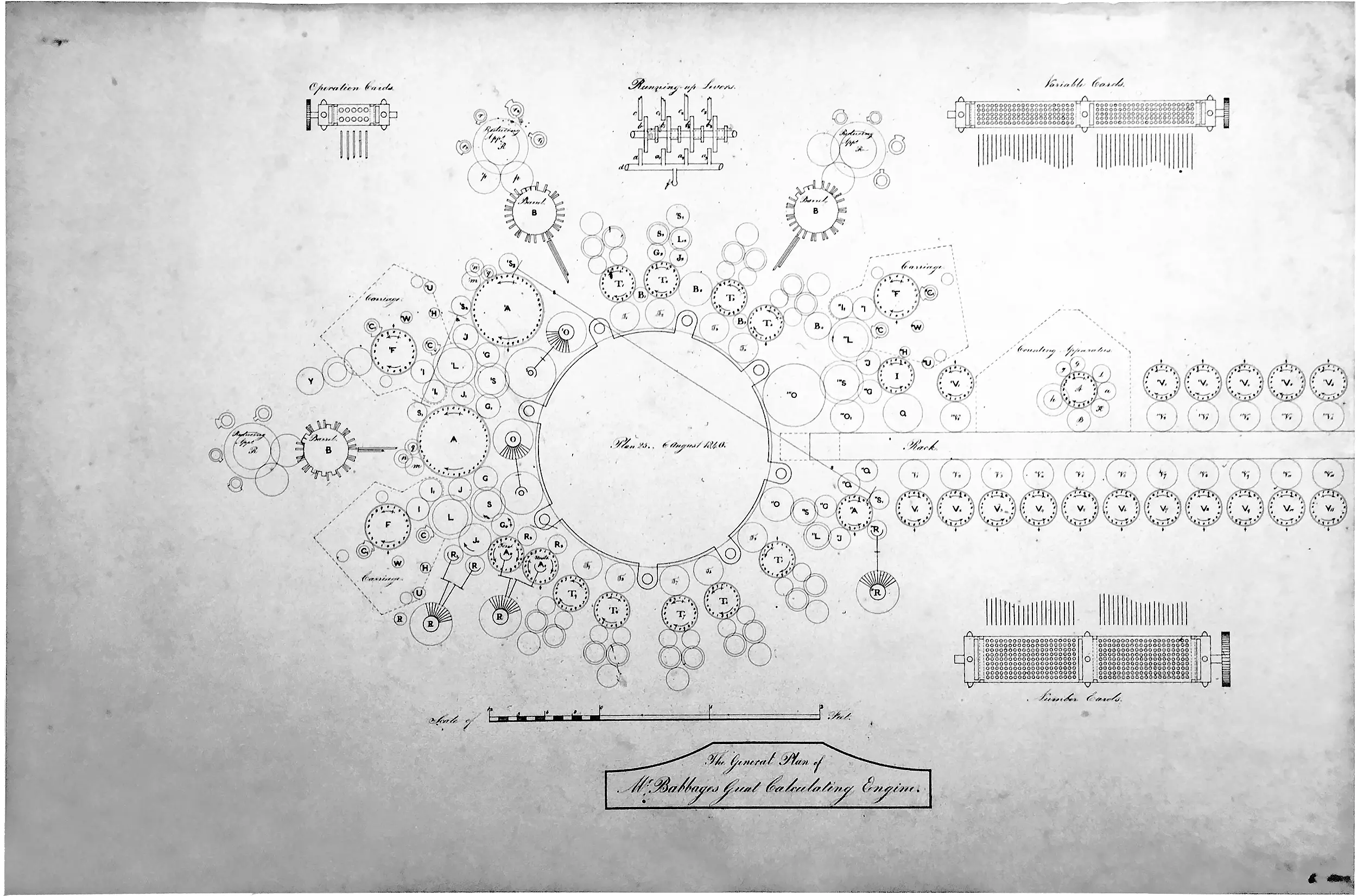

Prony’s project greatly impressed Charles Babbage (1791–1871), designer of the first general-purpose computer, the “Analytical Engine,” in the 1830s. Entirely mechanical, the Analytical Engine would have been steam-powered and would likely have taken about three seconds to perform an addition—far slower than any electronic computer, but still faster than doing it by hand. 14

Although known today as a hapless inventor too far ahead of his time (neither the Analytical Engine nor its more modest predecessor, the “Difference Engine,” were built in his lifetime), Babbage was no idle dreamer. He was in fact one of the Industrial Revolution’s great architects and theorists; his most important book, On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, was all about factory automation. It was full of down-to-Earth engineering and entrepreneurial advice, gleaned through close observation and obsessively backed up with productivity data.

Reconstruction of Babbage’s Difference Engine #2 at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California

Steampunk computing engines are just one (uncharacteristically speculative) idea among many in Babbage’s book. He introduced automatic computing in a chapter about the division of labor, noting: “The proceeding of M. Prony, in [his] celebrated system of calculation, much resembles that of a skilful person about to construct a cotton or silk mill, or any similar establishment.” 15 In short, like Prony, Babbage sought to “manufacture logarithms.” Mechanical calculation was simply a means to automate the jobs of Prony’s hairdressers.

The parallel Babbage drew to textile mills is telling, for his other great inspiration was the Jacquard loom, patented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1804. Jacquard’s machine made the mass reproduction of complex patterned fabrics possible by encoding their designs as holes punched into a sequence of cards. Similar punched cards were to be the data input and storage mechanism for the Analytical Engine. 16

Jacquard loom at the Paisley Museum in Scotland

Ada Lovelace, aged seventeen, 1832

In 1833, Baroness Anne Byron, an educational reformer and philanthropist, took her seventeen-year-old daughter Ada, the future Countess of Lovelace (1815–1852), to a soirée at Babbage’s house. 17 As Lady Byron wrote soon afterward, “We both went to see the thinking machine (for such it seems) last Monday. It raised several No.’s to the 2nd and 3rd powers, and extracted the root of a quadratic equation. […] There was a sublimity of the views thus opened of the ultimate results of intellectual power.” They had witnessed a demonstration of a working prototype of the Difference Engine—as sophisticated a computer as anyone then alive would ever see in operation. 18

Despite her youth, Ada Lovelace (as she is usually called today) understood the far-reaching implications of the machine. Over the following years, she became Babbage’s intellectual collaborator as the incomplete Difference Engine gave way to grander (and even less complete) plans for its fully programmable successor, the Analytical Engine.

Babbage’s master plan of the Analytical Engine

Analytical Engine model by Sydney Padua

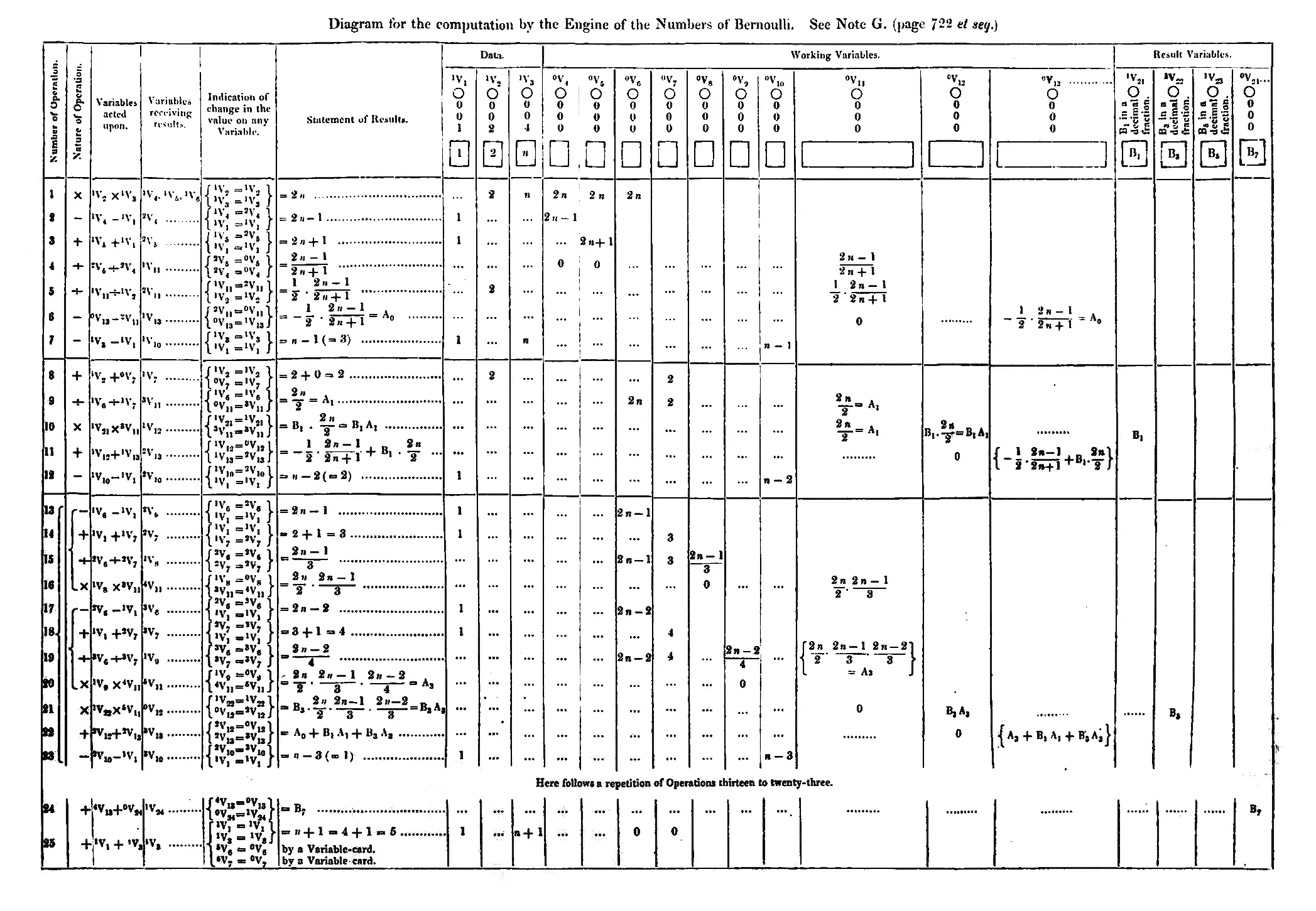

In 1842, Lovelace translated a lecture on the Analytical Engine given by Italian military engineer Luigi Menabrea, appending to it a series of notes far lengthier and more insightful than the lecture itself. Note G includes the first published computer program for the Analytical Engine—hence the first published program, period. It calculated Bernoulli number sequences, which turn up often in mathematical analysis. As Lovelace famously wrote, “The Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns, just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves.” 19 This observation was even sharper than it first appears, for she likely understood that the algebraic patterns in real flowers and leaves are themselves woven computationally, producing the mathematical regularities of petals, veins, leaves, and branches discussed in chapter 1. 20

Lovelace’s program for the computation of Bernoulli numbers, from Note G of Sketch of the Analytical Engine, 1842

To what degree, though, should one think of a computer as a mere “loom” for the mass production of mathematical tables? Babbage’s computing engines included a beautiful design for a printer capable of creating stereotype plates of whole finished pages. But there is a notable difference between the labor involved in printing tables (or manufacturing pins, or weaving cloth) and actually calculating those tables: the former kind of labor is physical, while the latter is mental.

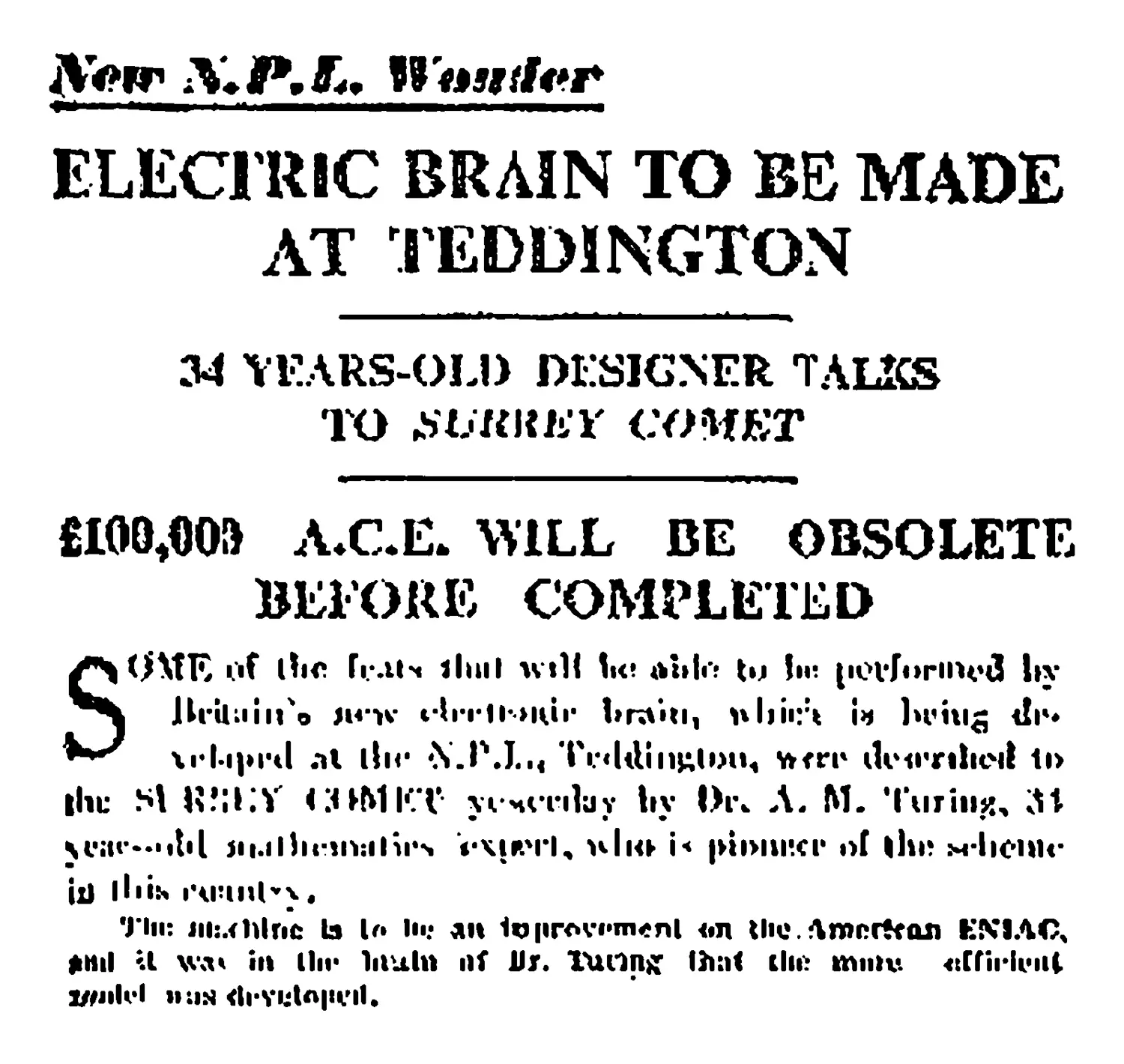

The Surrey Comet, 1946

This suggests a functional (not just metaphorical) analogy between computers and brains. The analogy has been used liberally by journalists over the years; for instance, in 1946, the Surrey Comet described Turing’s Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) as an “Electric Brain to be Made at Teddington.” 21 When the long-delayed ACE was finally completed in 1950, the newspapers once again referred to it as an “electric brain,” “electronic brain,” or “‘brain’ machine.” 22 We tend to dismiss such headlines as old-timey clickbait, but this glosses over the genuine insight behind Lady Byron’s characterization of the Difference Engine as a “thinking machine.”

Newspaper clippings about Turing’s Automatic Computing Engine from 1950

Nowadays, we prefer terms like “information processing” to avoid the baggage of consciousness and subjective experience implied by words like “thinking” and “mental,” but we should keep in mind that, to a committed industrialist like Babbage, subjectivity simply wasn’t relevant. As far as we know, he didn’t give the question of “what it was like to be” a mechanical computer a moment’s thought; then again, neither did he trouble himself with “what it was like to be” a human computer. Factory work was purely functional, operating at a level of abstraction above the individual—hence the substitutability of workers on a production line. As Babbage put it, “[D]ivision of labor can be applied with equal success to mental as to mechanical operations.” 23

Lady Byron was excited by the “sublimity of the views thus opened of the ultimate results of intellectual power,” but, for others, the idea of machines doing mental labor sparked an early glimmer of the unease some feel about AI today. In 1832, a year before Lovelace and Babbage met, the London Literary Gazette had referred to Babbage, perhaps only half in jest, as a “logarithmetical Frankenstein.” 24 Information work may not have been a significant sector of the labor market yet, but the prospect of machines thinking still induced a certain agitation.

Der Golem, 1920

Just how far could a mechanical monster’s mental functions advance? According to Menabrea, the Italian engineer, “The [Analytical Engine] is not a thinking being but simply an automaton which acts according to the laws imposed on it.” Lovelace agreed, writing in her Note G, “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can [only] do whatever we know how to order it to perform.” 25 This zombie-like picture recalls the golem of medieval Jewish folklore: a clay figure animated by a powerful rabbi using magical incantations—that is, code. The golem may follow commands, but without understanding or discernment.

George Boole may have thought otherwise. Recall that, like Leibniz, Boole believed in binary logic as a universal calculus for reasoning. Boole went further, asserting that it is the way the mind reasons; hence the title of his great treatise, An Investigation of the Laws of Thought, published to wide acclaim in 1854. 26 Presumably, he meant that understanding and discernment were themselves products of logic, for while Boole was religious, he (again, like Leibniz) thought of logic and rationality as inherently divine. 27 The human soul was a “rational soul,” and our subjectivity followed from, rather than existing in spite of, our rationality.

In the beginning, this neuroscientific aspect of Boole’s thesis remained largely unacknowledged. A notable exception was Boole’s friend and colleague Augustus De Morgan (author of the “Great fleas have little fleas” rhyme in chapter 1), who had himself been working on the foundations of logic. 28 The Victorian intelligentsia was a small world: De Morgan was also Ada Lovelace’s mathematics tutor, and had taught her calculus and the Bernoulli numbers.

Unlike her contemporaries, though, Lovelace was not content to choose between logic-based brains, on one hand, and mystical non-explanations of mental processes, on the other. In an 1844 letter to a friend—a decade prior to Boole’s Laws of Thought—Lovelace wrote, “I have my hopes […] of one day getting cerebral phenomena such that I can put them into mathematical equations; in short a law or laws, for the mutual actions of the molecules of brain […]. The grand difficulty is in the practical experiments.”

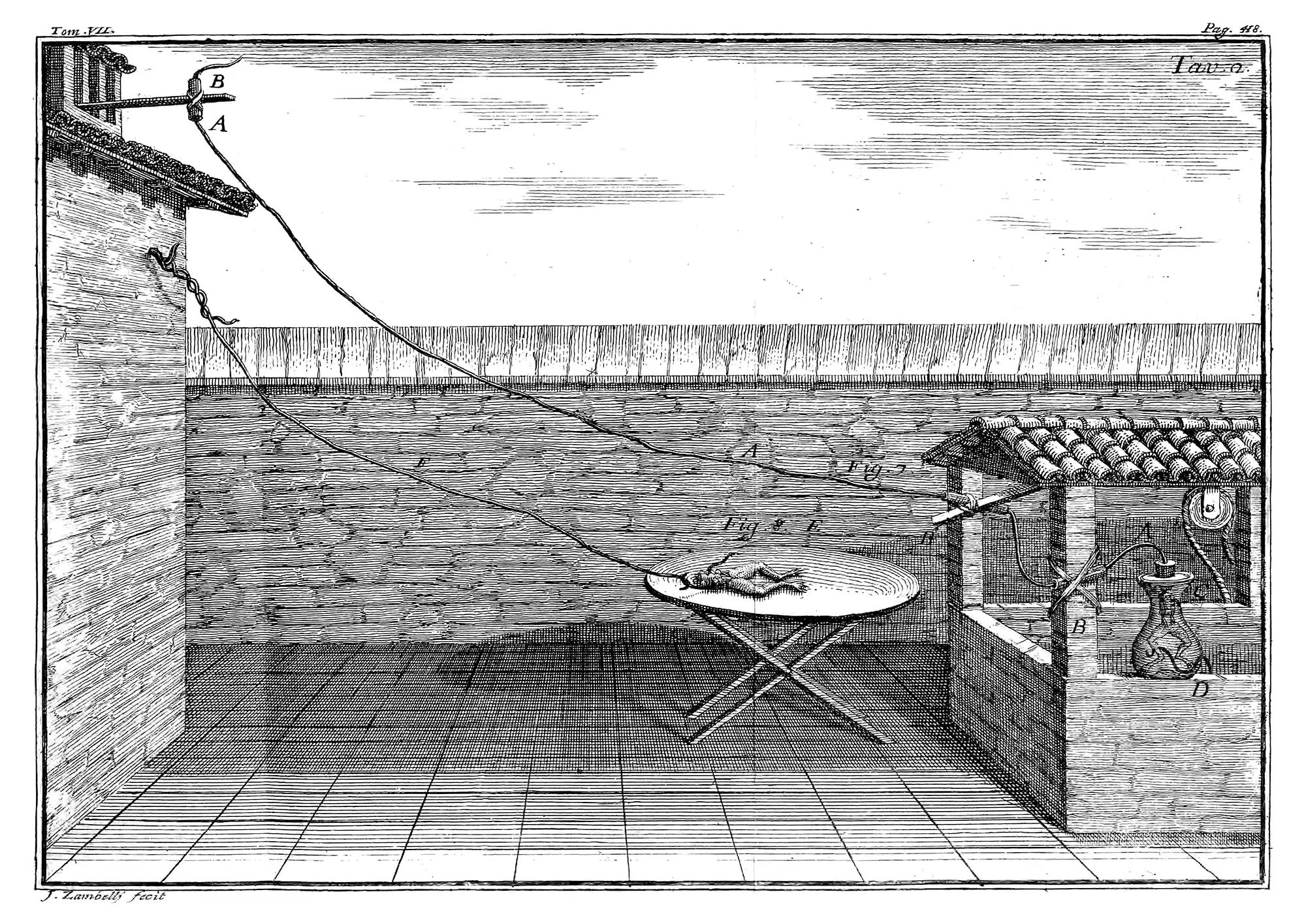

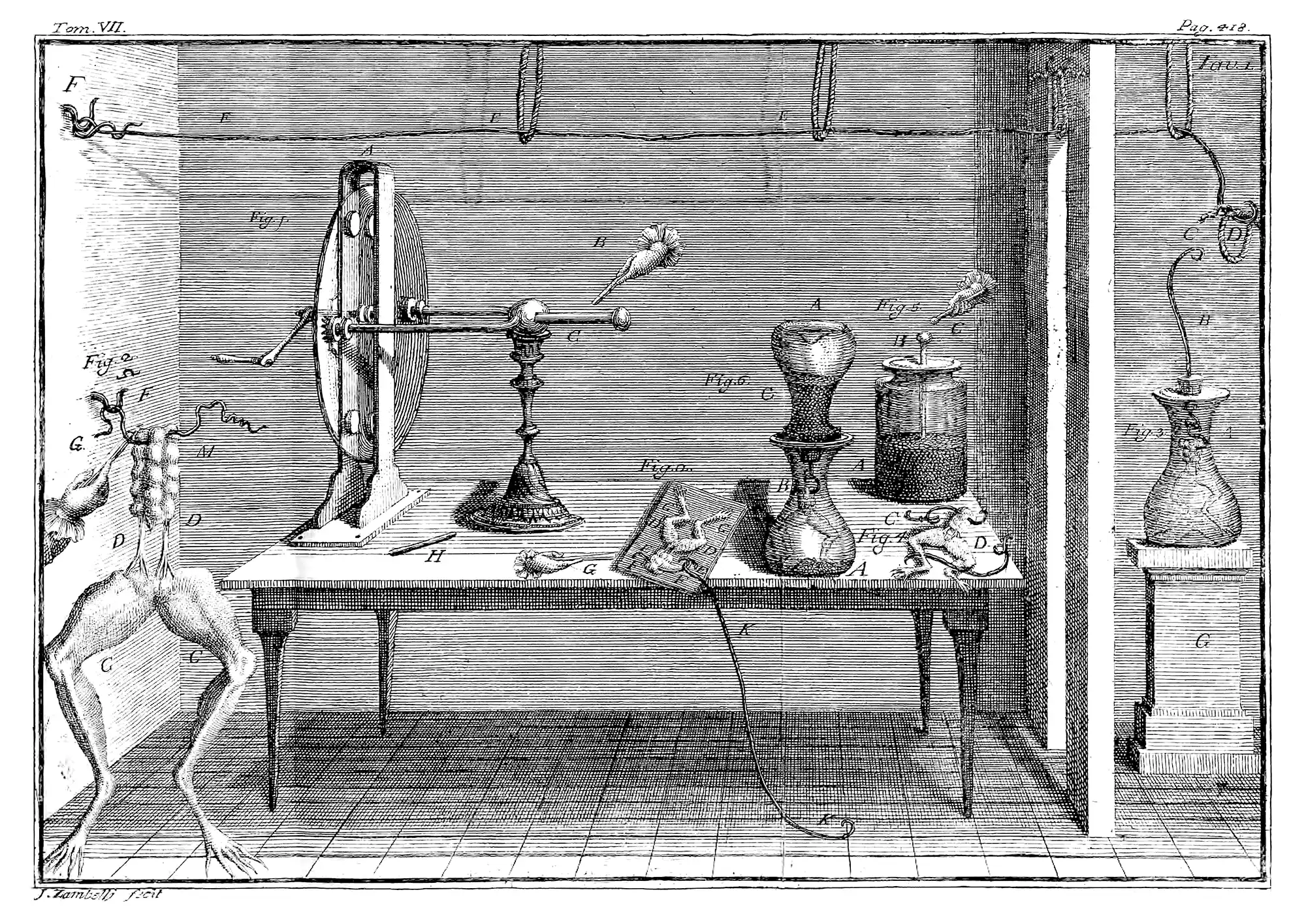

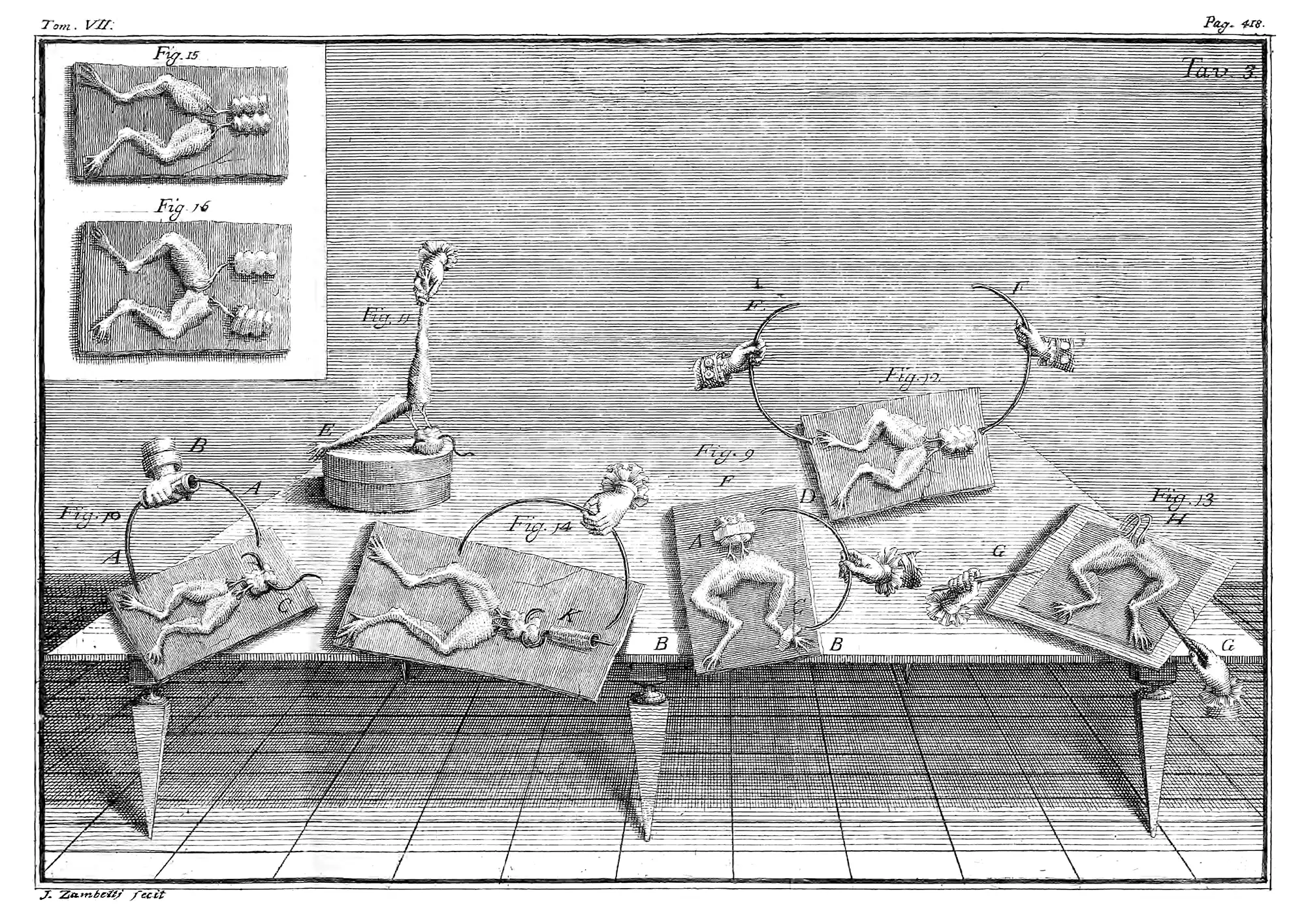

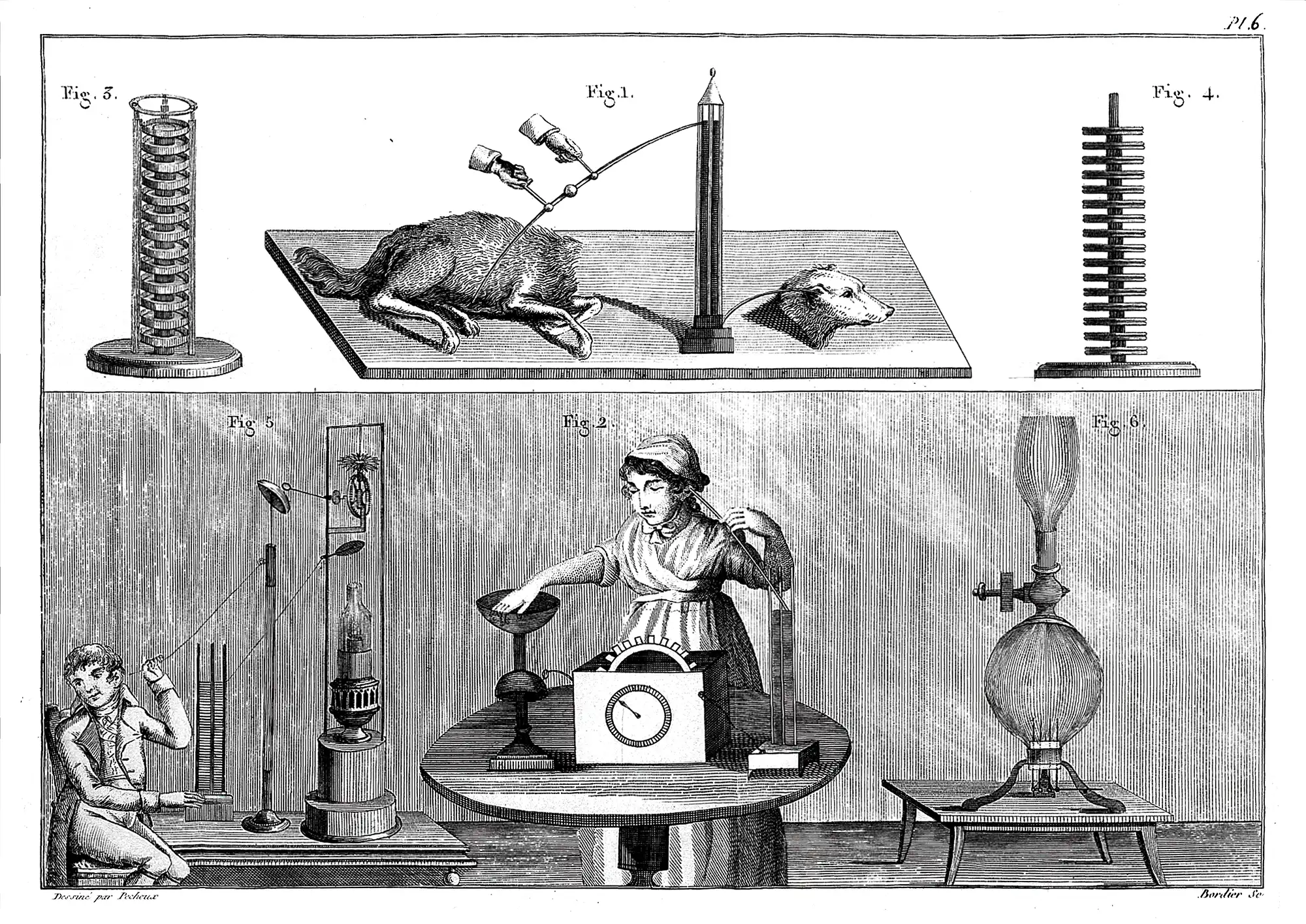

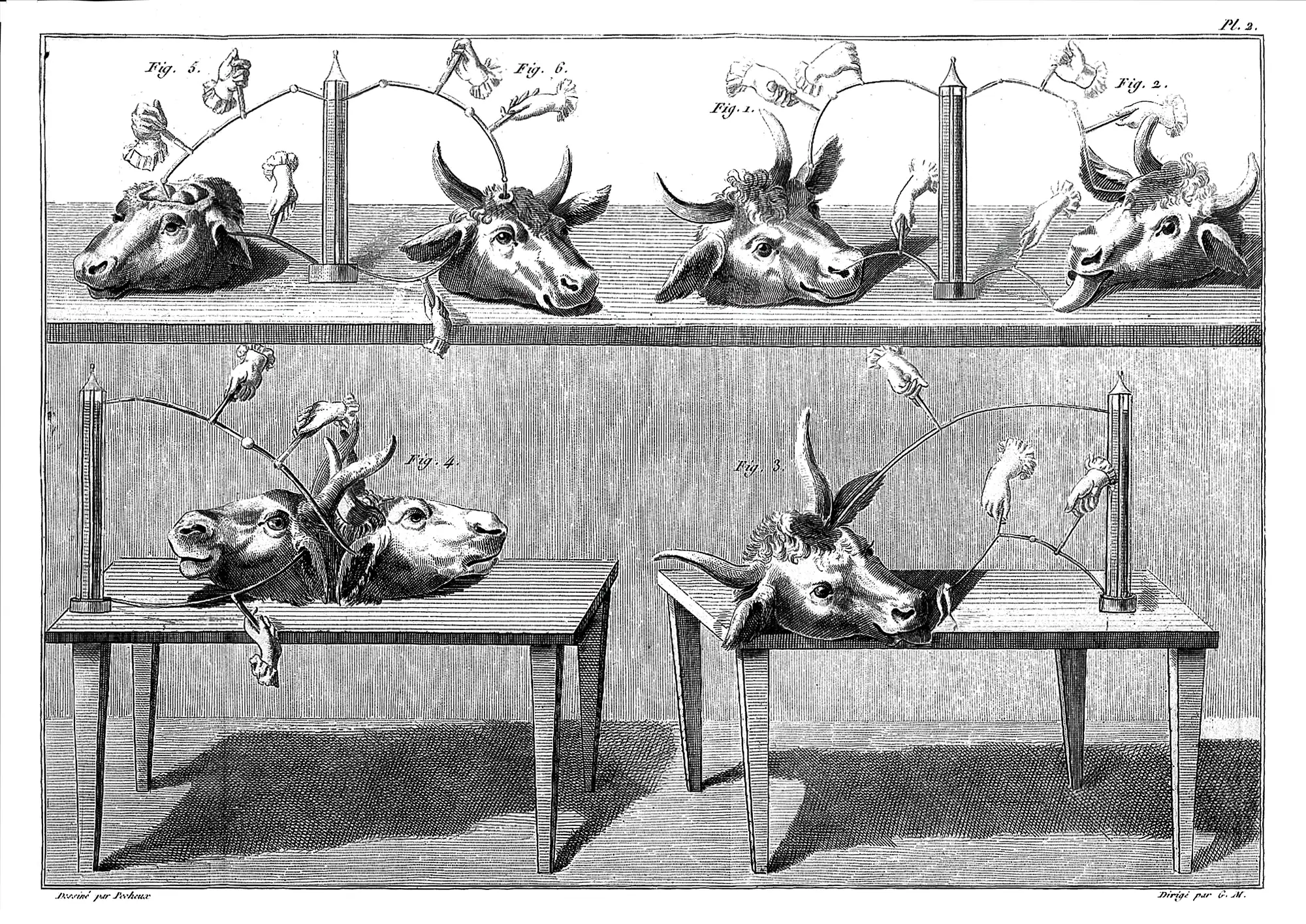

Electrophysiological experiments by Luigi Galvani

Electrophysiological experiments by Luigi Galvani

Electrophysiological experiments by Luigi Galvani

Electrophysiological experiments by Luigi Galvani

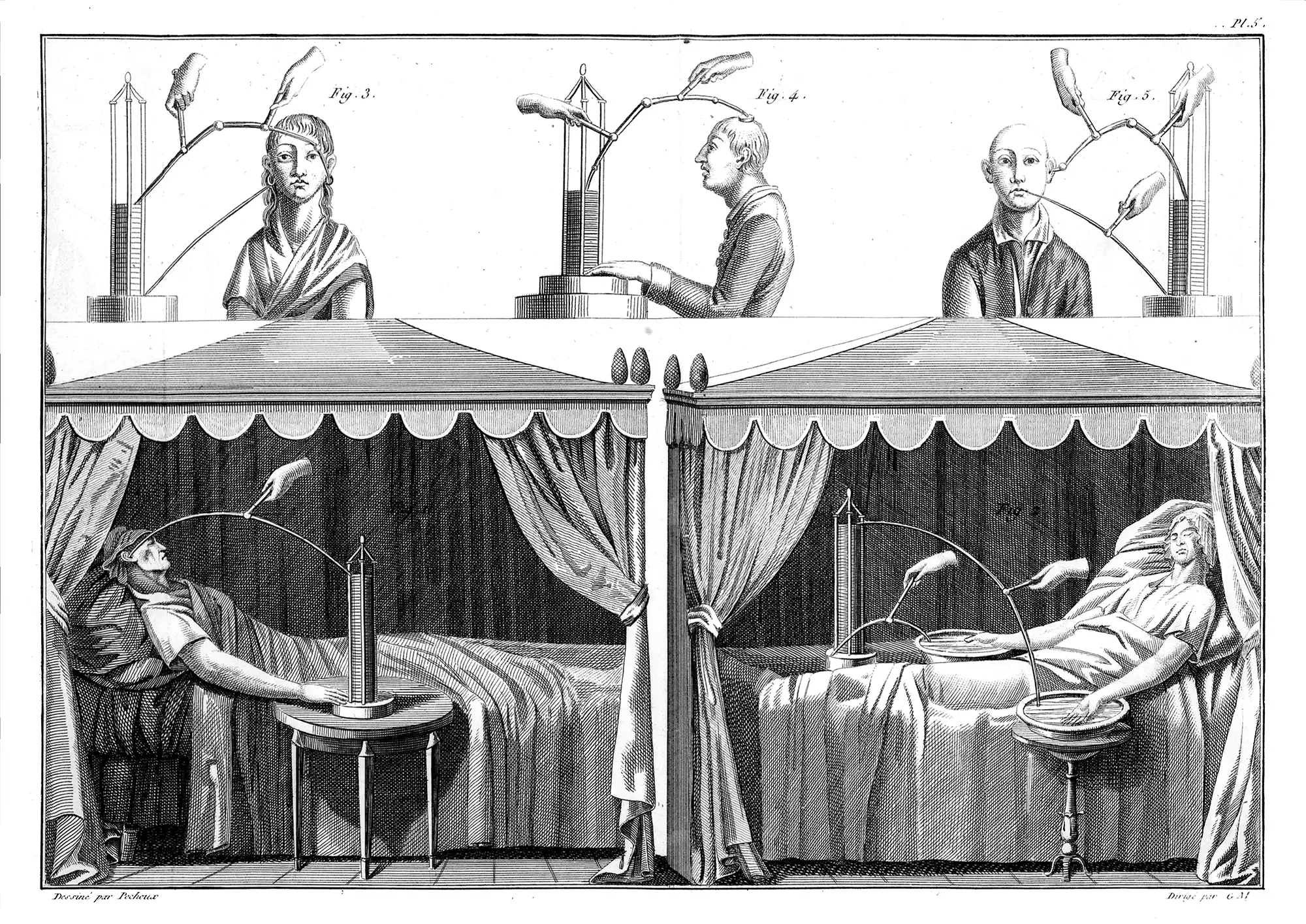

Lovelace undoubtedly knew about the sensational experiments of Luigi Galvani (1737–1798). Galvani had discovered that the application of electrical current to the nerves of freshly killed frogs caused their legs to twitch. Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini (1762–1834), carried on the work, legitimizing his studies with claims—not wholly implausible—that “galvanic” shocks could sometimes revive the drowned and treat the mentally ill. Twentieth-century defibrillation paddles and electroconvulsive shock therapy are heirs to these early experiments.

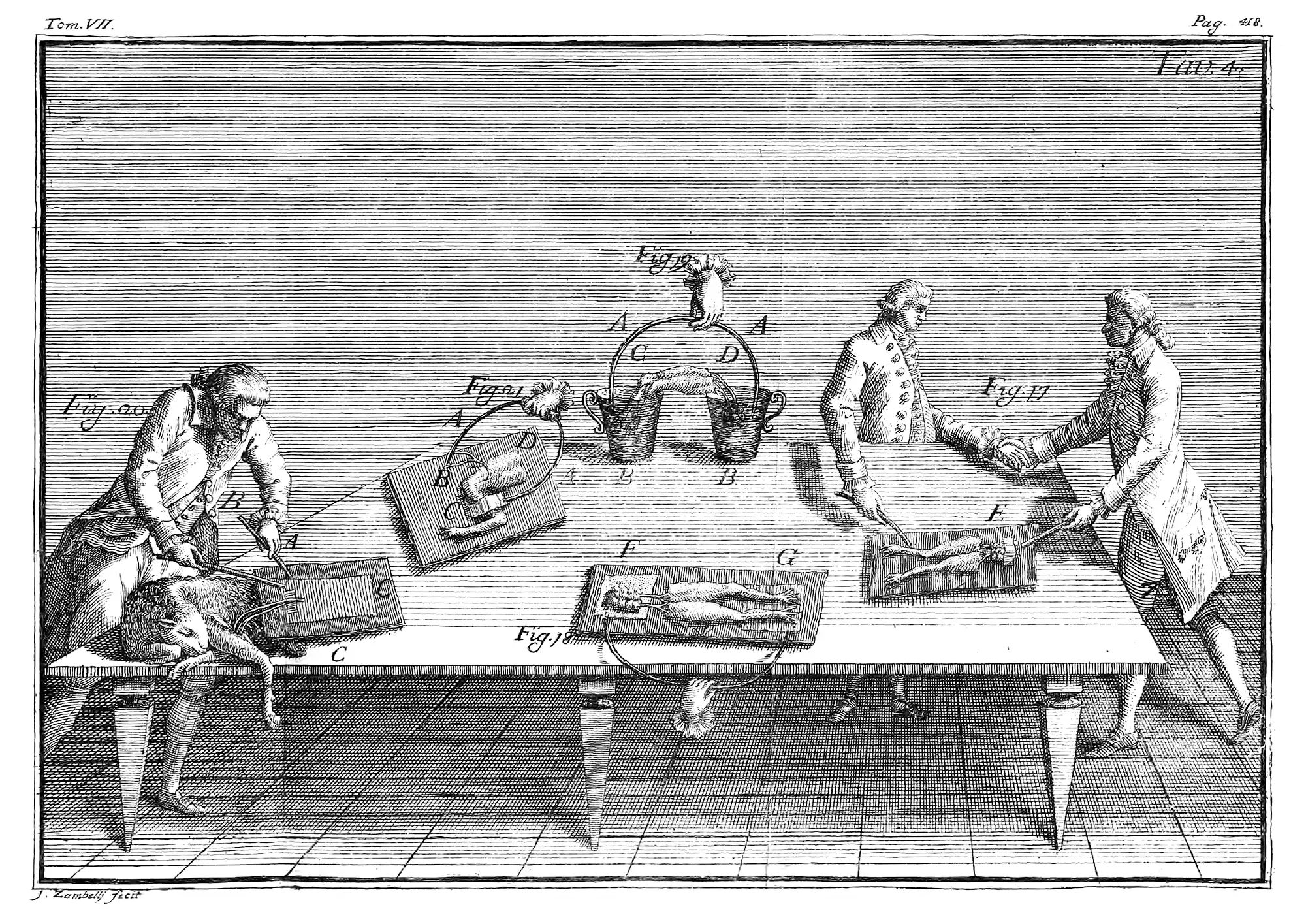

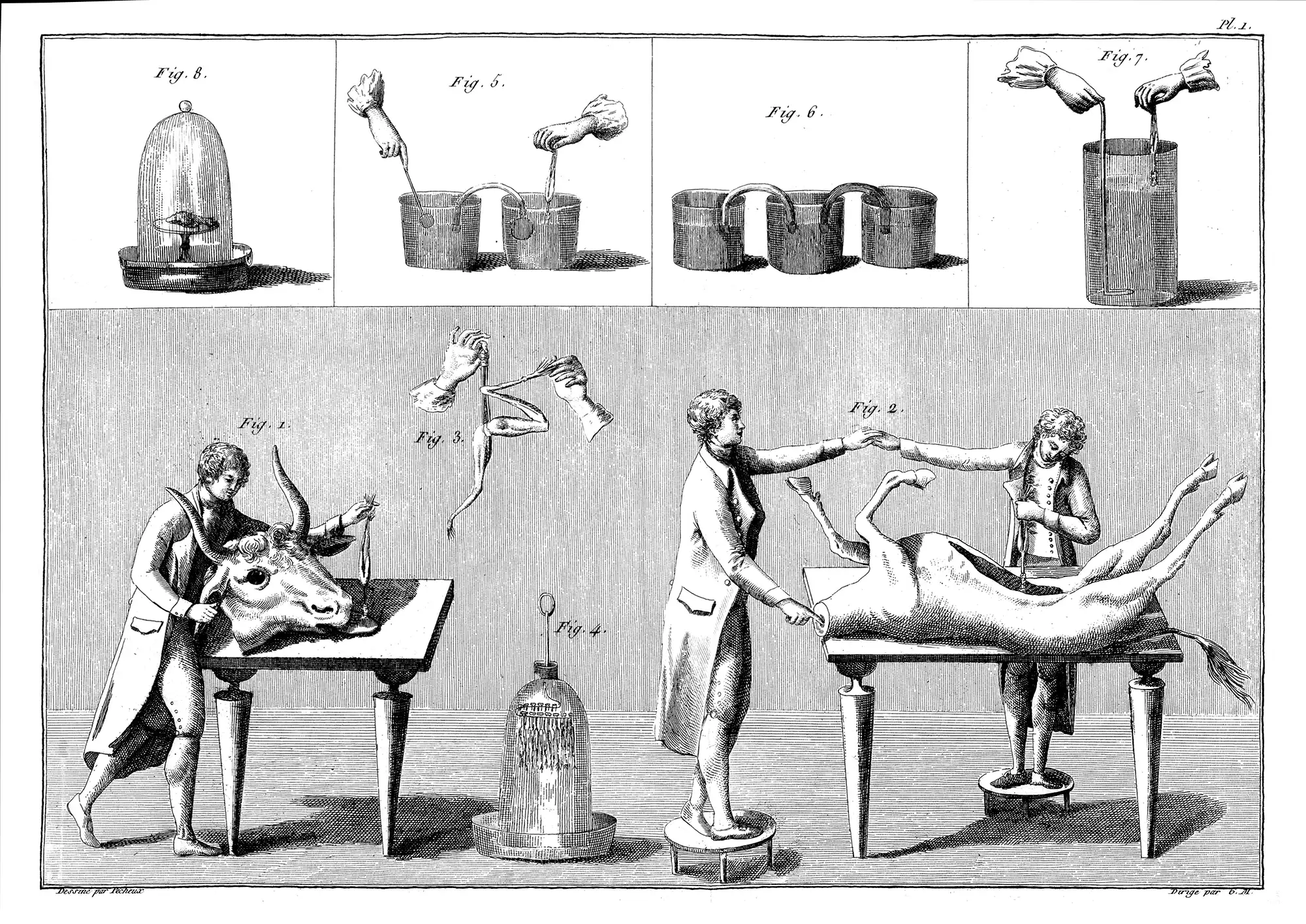

Still, Aldini appears to have been more of a showman than a scientist. In 1803, he rushed the hanged body of convict George Foster from London’s Newgate Prison to the Royal College of Surgeons for an anatomical demonstration. 29 According to the lurid (and wildly popular) Newgate Calendar, “On the first application of [electricity] to the face, the jaws of the deceased criminal began to quiver, and the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.” 30 The beadle of the Surgeons’ Company reportedly died of fright soon after returning home.

Electrophysiological experiments by Giovanni Aldini

Electrophysiological experiments by Giovanni Aldini

Electrophysiological experiments by Giovanni Aldini

Electrophysiological experiments by Giovanni Aldini

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein 31 was probably inspired by this account. Perhaps likewise inspired, Lovelace wrote, underlining words with her customary enthusiasm: “I must be a most skillful practical manipulator in experimental tests; & that, on materials difficult to deal with; viz: the brain, blood, & nerves, of animals. [… N]one of the physiologists have yet got on the right tack; I can’t think why. […] It does not appear to me that cerebral matter need be more unmanageable to mathematicians than sidereal & planetary matters & movements, if they would but inspect it from the right point of view. I hope to bequeath to the generations a Calculus of the Nervous System.” 32

In drawing a parallel between neural activity and Newtonian laws of motion, Lovelace implied that cerebral “calculus” would not be founded on abstract logic like that of Boole and the Analytical Engine, but rather should be grounded in experiment, and, in this, she was indeed on the right tack.

Unfortunately, Lovelace’s health, always fragile, soon worsened. She began taking opiates for chronic pain, and died a few years later, at age thirty-six, of uterine cancer. We will never know what she might have achieved as a neurophysiologist or as the first computational neuroscientist.

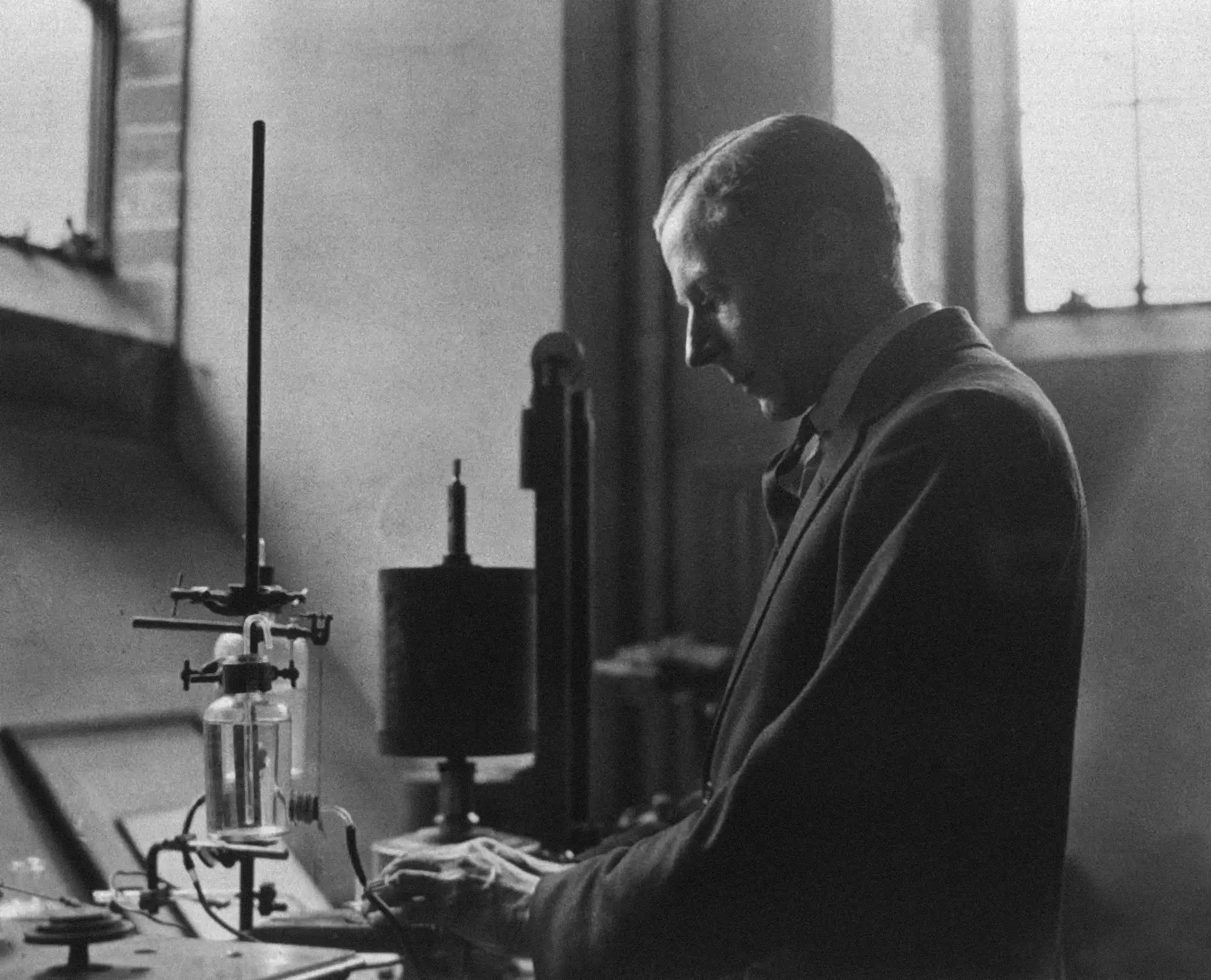

When real experiments with nerve tissue finally got underway, they at first seemed to confirm the “digital” intuitions of Leibniz and Boole. In the 1920s, pioneering English neuroscientist Edgar Adrian was electrically recording “all-or-nothing” action potentials, or “spikes,” in the sensory neurons of dissected frogs at his lab at Cambridge. 33 Adrian’s colleague and predecessor, Keith Lucas, had already established that impulses in motor-nerve fibers were similarly all-or-nothing. 34

Edgar Adrian in the laboratory, around 1920

With neural inputs and outputs thus seemingly binary electrical signals, the idea that the brain is a logic machine carrying out a kind of calculus ratiocinator gained powerful support. In particular, if every neuron has inputs corresponding to Boolean ones and zeros, and produces a Boolean output in response, it’s a logic gate—that is, a Boolean operator. 35 And, if so, the activity of the brain as a whole would amount to a vast logical calculation.

Two pivotal figures in modern neuroscience, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts, brought these ideas together in a legendary 1943 paper, “A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity.” It seemed to be the realization, ninety-nine years after Lovelace’s letter, of her envisioned “Calculus of the Nervous System”:

To psychology, […] specification of the [neural] net would contribute all that could be achieved in that field—even if the analysis were pushed to the ultimate psychic units or ‘psychons,’ for a psychon can be no less than the activity of a single neuron. […] The ‘all-or-none’ law of these activities, and the conformity of their relations to those of the logic of propositions, insure that the relations of psychons are those of the two-valued logic of propositions. Thus in psychology […] the fundamental relations are those of two-valued logic. 36

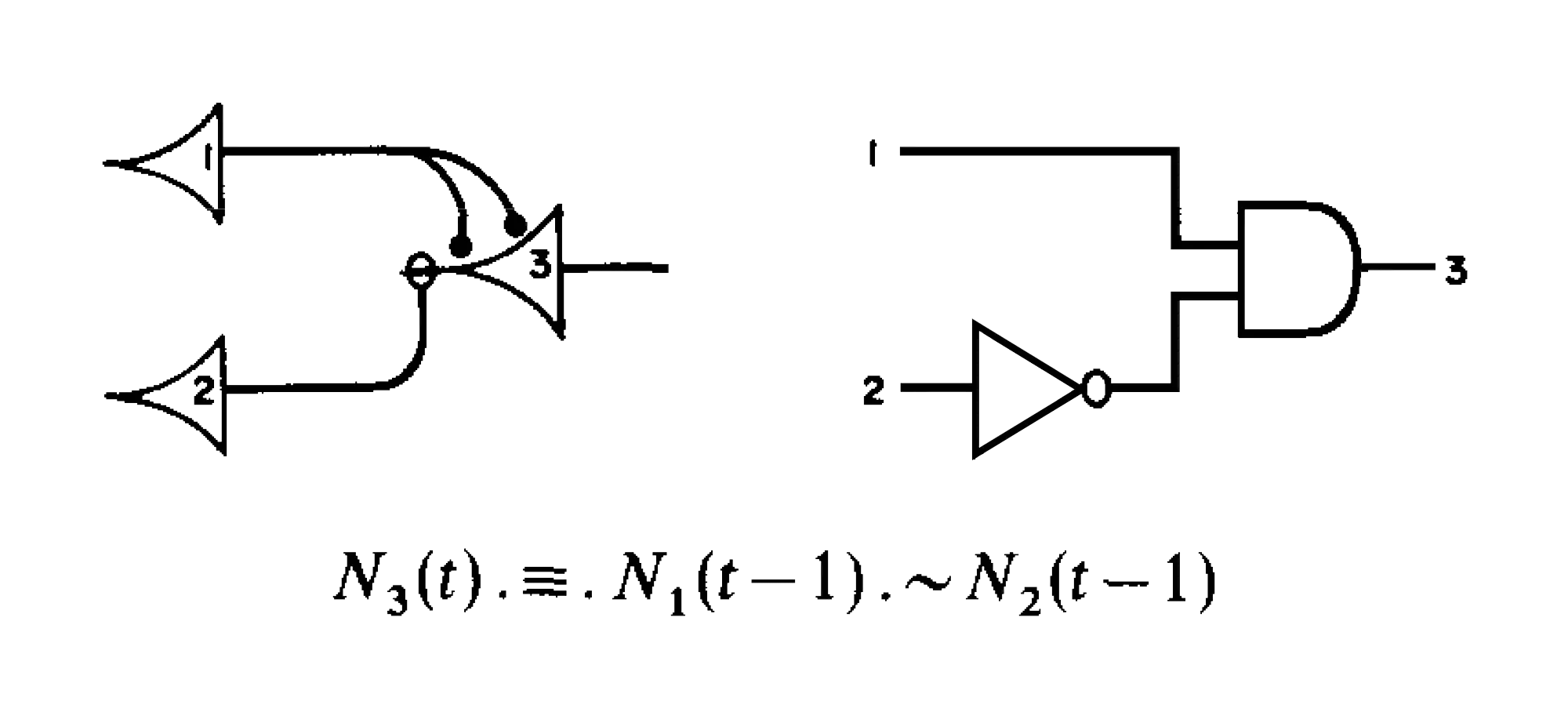

This paper was at once an end, a beginning, and a turning point—but not in any way its authors could have foreseen. As an engineering manifesto, it proved highly influential. John von Neumann read McCulloch and Pitts’s 1943 paper as a blueprint for how to perform general-purpose computation using electronic logic gates in place of biological neurons (as mentioned in chapter 1). In the right configurations, these gates—first made using vacuum tubes, and later transistors—could implement a Universal Turing Machine, and could therefore compute anything. The Boolean architecture was more minimal and elegant than that of the Analytical Engine and its successors, which relied on complex mechanical components and used base-ten arithmetic. 37

One can think, then, of digital computers as Universal Turing Machines built of hand-crafted neural networks of McCulloch-Pitts-type neurons. The symbols used today to represent logic gates are cribbed directly from the graphical representations McCulloch and Pitts drew of “pyramidal neurons” (which were, as the name implies, pyramid-shaped). We still draw a little circle at the tip of the pyramid for logical negation (turning an AND gate into NOT-AND or NAND, an OR into a NOT-OR or NOR, etc.). Originally, that circle represented an inhibitory synapse, which McCulloch and Pitts believed to implement the NOT operator. 38

Left: three-neuron logical circuit from McCulloch and Pitts 1943 (with their somewhat awkward notation for the logical operation being carried out below). Right: equivalent circuit using modern logic gate symbols. Note the neuron shapes and the small circle representing the NOT operation, which McCulloch and Pitts believed to be implemented by an inhibitory synapse.

Despite its powerful influence on computer engineering, as a neuroscientific theory, the 1943 McCulloch-Pitts paper was a false start. It marked the endpoint and high-water mark of the notion that individual neurons work by carrying out logical operations. Postwar neuroscientists quickly established that while all-or-none voltage spikes are indeed a key signaling mechanism in the brain, they don’t correspond to logical propositions, and neurons don’t work like logic gates. 39

Larger-scale electrical fields and oscillations matter too; neither is electrical signaling the whole story. A wealth of neurotransmitters and neuromodulatory chemicals operate at a variety of scales, from local signaling with specialized “neuropeptides” 40 to hormones secreted into the bloodstream that affect the entire body. These play major roles in our mental states, emotions, and drives. The emerging picture remains computational, but more in the spirit of Turing’s models for morphogenesis and “unorganized” neural networks rather than anything like a calculus ratiocinator.

Turing understood this, as he made clear in a 1951 BBC Radio address. 41 He agreed with Lovelace’s assertion that writing a program in the usual way could only produce a predefined golem-like result—indeed, traditional programming involves writing code whose function is fully understood by the programmer in advance, foreclosing any possibility for subsequent machine behavior we could reasonably call “creative” or “intelligent.” However, the universality of computing makes it possible to implement any computable model of neural function, including Lovelace’s “calculus of the nervous system,” on any Universal Turing Machine. Thus, Turing said, “it will follow that our digital computer, suitably programmed, will behave like a brain.”

Although, like Turing, neuroscientists understood long ago that the brain is not a classical logic machine, the message took a long time to sink in among computer scientists and AI researchers. Recall that, throughout the twentieth century, repeated attempts at hand-writing algorithms to carry out the most basic of everyday tasks, like image and speech recognition, robotic control and common-sense reasoning, had failed utterly, bringing on the AI winters mentioned in the introduction. 42

For many decades, then, computers were able to perform logic-based tasks that had been deemed purely “mechanical” with superhuman speed, yet seemed unable to get anywhere at everyday “human” tasks. They failed even at tasks that many other animals with much smaller brains find easy. It began to seem that, despite Turing’s ideas about universal computation, computers might have little to do with either biology or brains after all. 43

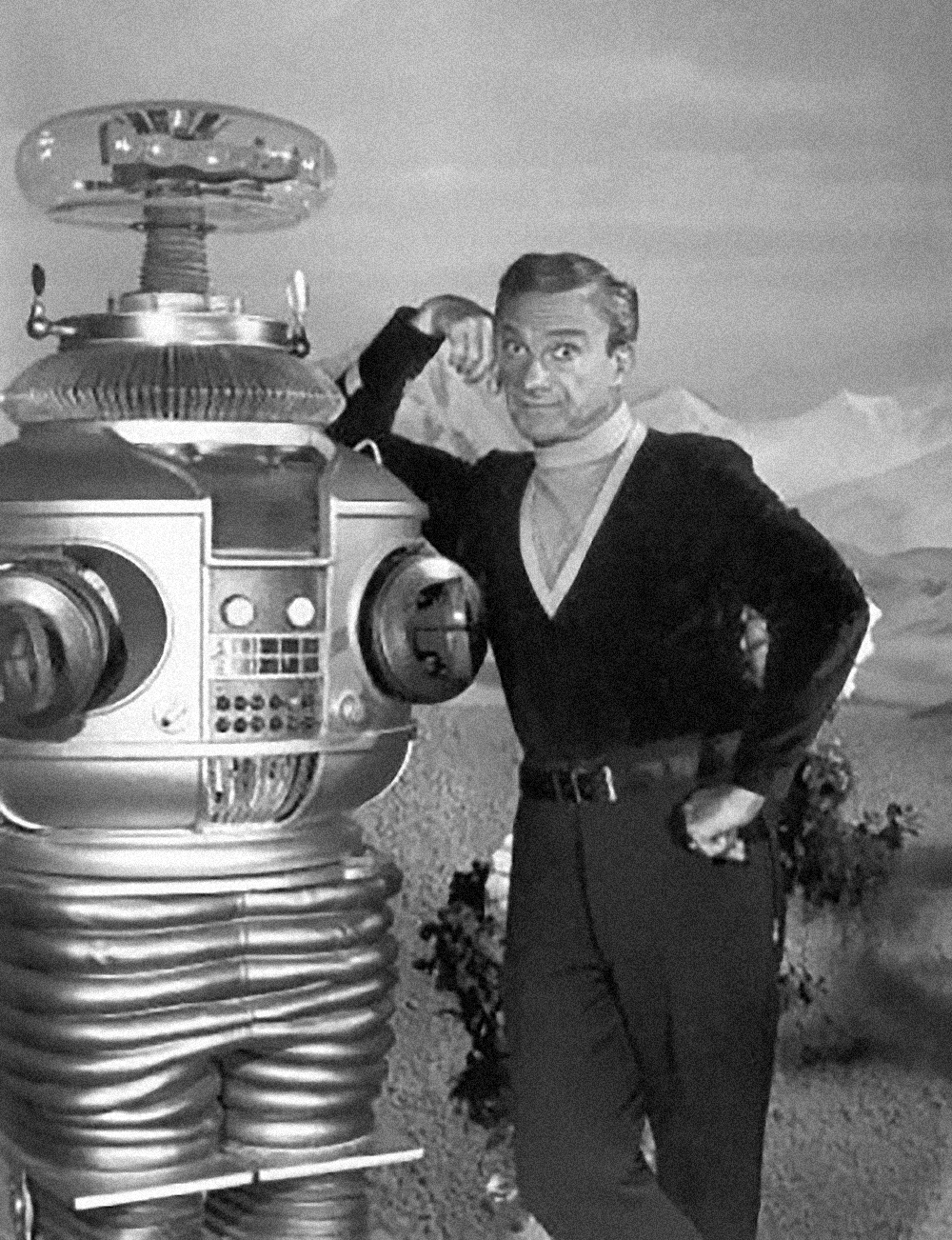

1967 publicity photo of actor Jonathan Harris and the Lost in Space robot, famous for the phrase “does not compute”

The popular culture of AI throughout the twentieth century navigated this apparent mismatch between brains and computers by imagining that when—or if—AI finally arrived, it would be stellar at “rational” thinking and logic but poor at human emotion, creativity, or common sense. HAL 9000, 44 or Data from Star Trek, are prime examples. 45

The message was: computers can perform rote calculations today, and may eventually exceed humans at “book smarts” too, but, being golem-like, they aren’t remotely like us; the human spirit is neither logical nor rational. We can’t be reduced to mere computation.

This trope seems especially irresistible to Hollywood, resurfacing over and over in franchises like The Terminator, Robocop, and The Matrix. If Boole was an Enlightenment thinker living in the Romantic period, Hollywood remains full of closet Romantics living in a Postmodern era.

What attracts us to this kind of human exceptionalism? Partly, the question answers itself; of course we like thinking of ourselves as fundamentally different, better in some non-quantifiable way, possessing some je ne sais quoi that will remain forever out of reach of the encroaching “other.” Nationalities and ethnic groups play this identitarian game all the time.

Beyond the obvious, though, the “incomputably human” narrative is comforting because the Industrial Revolution established a computational hierarchy wherein the soulless, rote, mechanical stuff is done at the lowest tier of the org chart of its time—first by calculating women, then by the machines that replaced them—so that upper class gentlemen-scholars could be freed for the more varied, creative, and intellectual pursuits they deemed worthy of being called “intelligent.” 46

As historian of science Jessica Riskin puts it, “Not only has our understanding of what constitutes intelligence changed according to what we have been able to make machines do but, simultaneously, our understanding of what machines can do has altered according to what we have taken intelligence to be. […] [T]he first experiments in automation were devoted to determining its uppermost limits, which simultaneously meant identifying the lowest limits of humanity.” 47

Today we not only face the problem that those limits have continued to shift, but also that they have stubbornly refused to fall into the right sequence, according to our class-based preconceptions. It’s easier nowadays to imagine a doctor replaced by an AI model than a nurse. We probably won’t have AI plumbers anytime soon, but AI physicists (at the very least AI physics research assistants) may arrive imminently. When large language models can read and summarize complex arguments, write essays and poems, create software, and so on, there ceases to be any obvious hierarchy of information tasks where a computer can only substitute for the work of the poorly paid or uneducated. AIs are no longer, as Leibniz would have it, “artificial peasants” manufacturing logarithms.

Neither is AI the purely book-smart supernerd envisioned by twentieth-century media. Real AI isn’t necessarily overly logical; in fact, its failures at solving logic puzzles, or even simple arithmetic problems, featured prominently in AI critique during the early 2020s. Now, not acting enough like a computer is interpreted as a lack of intelligence!

As an engineering discipline, too, modern AI is disruptive; it has little to do with the programming languages, data structures, and paradigms that were the mainstay of computer engineering departments a scant few years ago. AI models may run on Universal Turing Machines, but they aren’t algorithms in any classical sense. Instead, they tackle the problem of modeling probability distributions directly from data.

So where did the new approach to computing and AI come from? As it turns out, it has been here all along, just not in the mainstream. Understanding this alternative vision, and its relationships with other disciplines, requires following a different path from that of Leibniz, Boole, and traditional computer science—one that, inspired by living systems, conceived of computation less in terms of logic than in terms of learning and prediction.

This was the path of cybernetics, an idea developed as far back as the 1940s, in wartime, and already falling into disrepute by the ’60s.

More thorough histories often begin with the Antikythera mechanism, a mechanical astronomical computer recovered from a shipwreck in the Aegean sea thought to date back to the second century BCE. Many early civilizations performed astronomical and calendrical calculations, whether for navigation, agriculture, or religious rites. If by “computer” we simply mean something engineered to aid in such calculations, ancient archeological sites built to align with the sun, planets, and stars would also qualify.

Leupold 1727 ↩. Robert Hooke, of the Royal Society, was unimpressed: “As for ye Arithmeticall instrument which was produced here before this Society. It seemed to me so complicated with wheeles, pinions, cantrights, springs, screws, stops & truckles, that I could not conceive it ever to be of any great use.” Jardine 2017 ↩.

This translation is from B. Russell 1937 ↩.

Leibniz 1666 ↩.

The most influential mathematician of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, David Hilbert (1862–1943), had placed the Entscheidungsproblem at the center of his program for formalizing mathematics in the 1920s.

Leibniz wasn’t the first or only mathematician to discover binary; as with nearly every significant discovery or invention, it was made by a number of other thinkers around the same time, including Thomas Heriot (1560–1621), Francis Bacon (1561–1626), and Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz (1606–1682). See Glaser 1971 ↩.

Per Mary Everest Boole, “George afterwards learned, to his great joy, that the same conception of the basis of Logic was held by Leibniz […].” M. E. Boole 1901 ↩.

This also coincided with the early exuberance of the metric system, to sweep away older “irrational” and aristocratically tainted systems of measurement. Unfortunately for Prony, the metric approach to angles (one hundred grades to the right angle, instead of ninety degrees) never caught on, rendering many of the tables useless.

According to Babbage 1832 ↩, “[T]hese persons were usually found more correct in their calculations, than those who possessed a more extensive knowledge of the subject.”

A. Smith 1776 ↩.

Martin 1992 ↩.

These class and gender iniquities would, of course, be endlessly repeated in centuries to come.

Bromley 1982 ↩.

Babbage 1832 ↩.

Per Babbage 1864 ↩, “To those acquainted with the principles of the Jacquard loom, and who are also familiar with analytical formulæ, a general idea of the means by which the Engine executes its operations may be obtained without much difficulty.” Jacquard-style punched cards were in fact used extensively for data processing and computing, right up until the 1980s.

Lovelace’s father was the notorious Romantic poet, Lord Byron; her parents had stayed together for less than a year, owing to Lord Byron’s instability and scandalous lifestyle (including, Lady Byron feared, an incestuous relationship with his half-sister).

A portion of this prototype survived, and is now at the Science Museum in London. The Difference Engine, like many special-purpose computing machines from the first half of the twentieth century, was not Turing complete; it could only tabulate a limited (though useful) repertoire of functions using the “method of differences” (math folk: the discrete version of a polynomial series).

Lovelace and Menabrea 1842 ↩.

The Fibonacci numbers are closely related to the Bernoulli numbers; see Byrd 1975 ↩.

Surrey Comet 1946 ↩. Earlier special-purpose computers were also regularly referred to this way, most famously “Old Brass Brains,” a long-lived mechanical computer for predicting tides invented in 1895 and in use by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey from 1910 to 1965.

National Physical Laboratory 1950 ↩.

Babbage 1832 ↩.

London Literary Gazette, The; and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, &c 1832 ↩; Shelley 1818 ↩.

Lovelace and Menabrea 1842 ↩. In his 1948 report on “Intelligent Machinery,” Turing referred to this as “Lady Lovelace’s Objection” to the idea that machines could be intelligent.

G. Boole 1854 ↩.

Labatut 2024 ↩.

According to his widow, Mary Everest Boole, in a 1901 letter: “nearly all the logicians and mathematicians ignored the statement that the book was meant to throw light on the nature of the human mind; and treated the formula entirely as a wonderful new method of reducing to logical order masses of evidence about external fact […]. De Morgan, of course, understood the formula in its true sense; he was Boole’s collaborator all along.” M. E. Boole 1901 ↩.

Knapp and Baldwin 1826 ↩.

Shelley 1818 ↩.

Letter of November 15, 1844, at Ashley Combe, to Woronzow Greig, Russian Ambassador in London. Lovelace 1992 ↩.

“Sensation is aroused by the messages which are transmitted through the nerves from the sense organs to the brain […]. [T]he messages […] consist of […] brief impulses in each nerve fibre; all the impulses are very much alike, whether the message is destined to arouse the sensation of light, of touch, or of pain.” Adrian 1928 ↩.

Lucas and Adrian 1917 ↩.

The basic Boolean operators take two inputs and produce one output; they are AND, OR, and XOR (short for “eXclusive OR”). AND outputs a one only if both inputs are one, and a zero otherwise; OR outputs a zero only if both inputs are zero, and a one otherwise; and XOR outputs a one if one and only one input is one. The single-input NOT operator inverts its input, outputting a one if the input is zero, and a zero if the input is one. Combinations of these operators can be used to make any more complex logical function.

McCulloch and Pitts 1943 ↩.

Harvard University’s Mark I computer, conceived by Howard Aiken in 1937 and built in the 1940s, was closely modeled on the Analytical Engine, including its reliance on base-ten arithmetic. After 1943, virtually all electronic computers used binary.

As mentioned earlier, all the computing pioneers took the step of going from logic machines designed to carry out a particular computational task to programmable general-purpose machines that, once built, could carry out coded instructions to perform any computational task—equivalent to a Universal Turing Machine. This was to be the difference between Babbage’s Difference Engine and the Analytical Engine. It was also the difference between the fixed-function computing machines made prior to 1945 and those after, with the ENIAC straddling the transition. (ENIAC began as a fixed-function computer that needed to be “programmed” by rewiring its plugboard, but it was updated to become fully programmable in software by 1947.)

Agüera y Arcas, Fairhall, and Bialek 2000 ↩.

S. J. Smith et al. 2020 ↩.

Turing 1951 ↩.

Haugeland 1985 ↩.

Richards and Lillicrap 2022 ↩.

Clarke 1968 ↩.

Although curiously, they took for granted that computers would soon be able to recognize faces and objects, understand speech, and perform many other everyday feats that had proven just as difficult. Perhaps these tasks seemed too cut-and-dried, too narratively uninteresting, or just too lowly to serve as a basis for human exceptionalism.

Such hierarchies of intelligence trace farther back—to Descartes, and even to Aristotle—but industrial production made the hierarchy even more literal.

Riskin 2003 ↩.