Abiogenesis

Spontaneous generation of birds and fish by a tree, depending on where its seeds land; Claude Duret, Histoire admirable des plantes et herbes esmerueillables et miraculeuses en nature, 1605

How did life on Earth begin? In the nineteenth century, this seemed like an unanswerable question. Researchers attempting to catch life in the act of “spontaneous generation” had come up empty-handed once they learned how to decontaminate their samples.

As William Thomson (1824–1907), the future Lord Kelvin, put it in an 1871 address before the British Association for the Advancement of Science, “Dead matter cannot become living without coming under the influence of matter previously alive. This seems to me as sure a teaching of science as the law of gravitation.” 1

Has life somehow always existed, then? Did it arrive on Earth from outer space, borne on an asteroid? Thomson thought so, and some still do. Not that this “panspermia” hypothesis really gets us anywhere. Where did the asteroid come from, and how did life arise there?

Despite his clear articulation of the principle of evolution, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) didn’t have a clue either. That’s why, in 1863, he wrote to his close friend Joseph Dalton Hooker that “it is mere rubbish, thinking, at present, of origin of life; one might as well think of origin of matter.” 2

Today, we have more of a clue, although the details may forever be lost to deep time.

Biologists and chemists working in the field of abiogenesis—the study of the moment when, billions of years ago, chemistry became life—have developed multiple plausible origin stories. In one, proto-organisms in an ancient “RNA world” were organized around RNA molecules, which could both replicate and fold into 3D structures that could act like primitive enzymes. 3 In an alternative “metabolism first” account, 4 life began without genes, likely in the rock chimneys of “black smokers” on the ocean floor; RNA and DNA came later. It may eventually be possible to rule one or the other theory out … or it may not.

We’ll return to RNA and replication, but let’s begin by unpacking the metabolism-first version in some detail, as it sheds light on the problem that confounded Darwin and his successors: how evolution can get off the ground without genetic heritability. As we’ll see, abiogenesis becomes less puzzling when we develop a more general understanding of evolution—one that can extend back to the time before life.

Lava lake, Kīlauea, Hawai‘i

Let’s cast our minds back to our planet’s origins. The Hadean Eon began 4.6 billion years ago, when the Earth first condensed out of the accretion disc of rocky material orbiting our newborn star, the Sun. Our planet’s mantle, runnier than it is today and laden with hot, short-lived radioactive elements, roiled queasily, outgassing carbon dioxide and water vapor. The surface was a volcanic hellscape, glowing with lakes of superheated lava and pocked with sulfurous vents belching smoke.

It took hundreds of millions of years for surface conditions to settle down. According to the International Astronomical Union, an object orbiting a star can only be considered a planet if it has enough mass to either absorb or, in sweeping by, to eject other occupants from its orbit. But in the chaos of the early Solar system, this took a long time. While Earth was clearing its orbit of debris, it was continually bombarded by comets and asteroids, including giant impactors more than sixty miles across. A single such impact would have heated the already stifling atmosphere to a thousand degrees Fahrenheit.

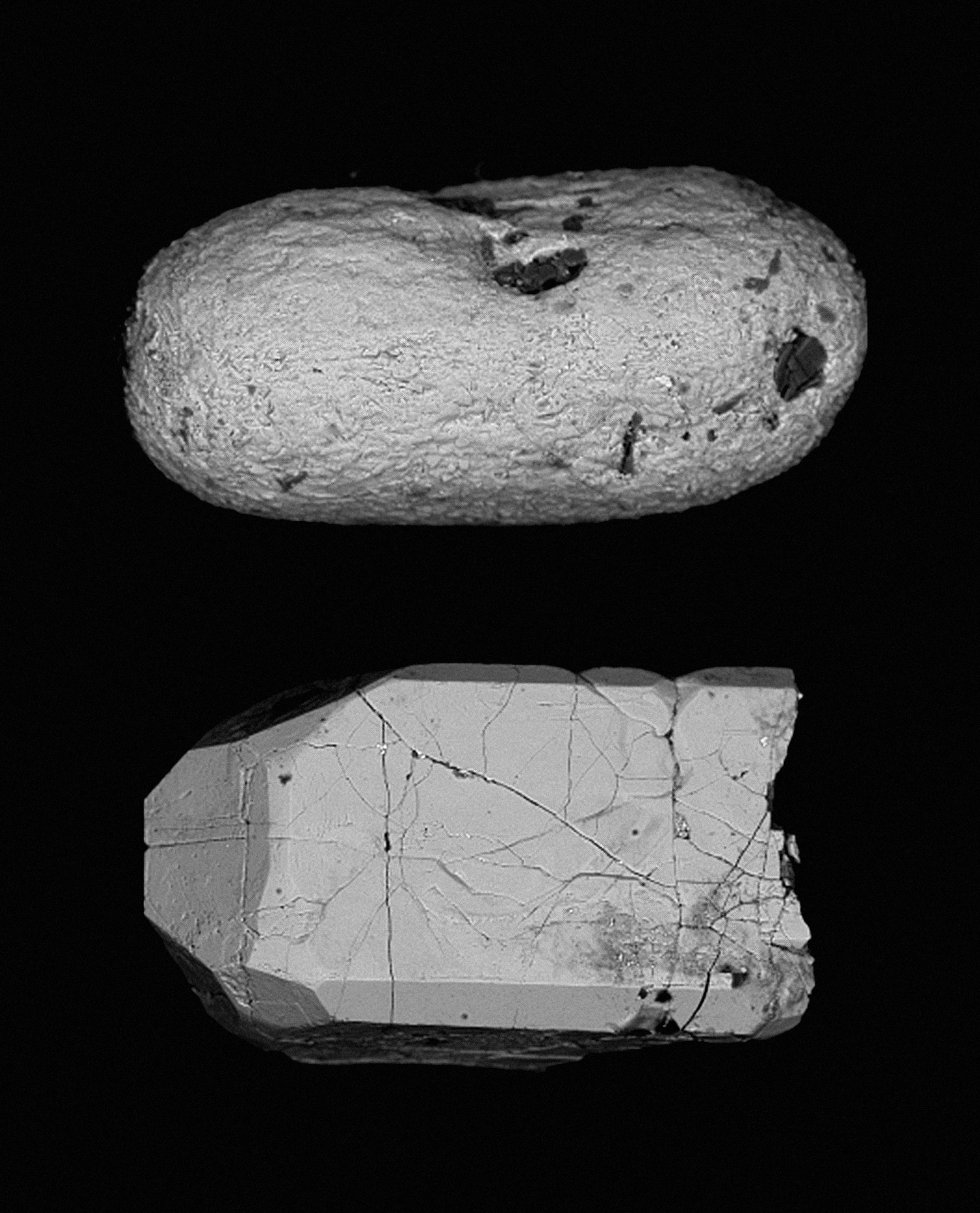

Backscatter electron micrograph of 4.4-billion-year-old detrital zircons from the Hadean metasediments of the Jack Hills, Narryer Gneiss Terrane, Western Australia

One of those collisions appears to have been with another newly formed planet, an event that came close to destroying the Earth altogether. According to this theory, enough broken, liquefied, and vaporized rock splashed into orbit to coalesce into the Moon.

Unsurprisingly, very little geological material survives from the Hadean—mainly zircon crystals embedded within metamorphic sandstone in the Jack Hills of Western Australia.

It’s difficult to imagine anything like life forming or surviving under such harsh conditions. Maybe, somehow, it did. We know for sure that by later in the Hadean or the early Archean—3.6 billion years ago, at the latest—the surface had cooled enough for a liquid ocean to condense and for the chemistry of life to begin brewing.

Today, those early conditions are most closely reproduced by black smokers. These form around hydrothermal vents on the mid-ocean ridges where tectonic plates are pulling apart and new crust is forming. In such places, seawater seeping down into the rock comes into contact with hot magma. Superheated water then boils back up, carrying hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and sulfur compounds, which precipitate out to build smoking undersea chimneys. Probes sent thousands of feet down to explore these otherworldly environments find them teeming with weird life forms of all kinds, attracted by warmth, nutrients, and each other. Some of the inhabitants may go a long, long way back.

The “Candelabra” black smoker in the Logatchev hydrothermal field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, at a depth of 10,800 feet

Like lava rock, the chimneys are porous, and the pores are ideal little chambers for contained chemical reactions to take place—potentially powered by a handy energy source, since the hydrogen gas creates proton gradients across the thin walls between pores, making them act like batteries. 5 Given energy, iron sulfide minerals in the rock acting as catalysts, and carbon dioxide bubbling through, self-perpetuating loops of chemical reactions can sputter to life, like a motor turning over.

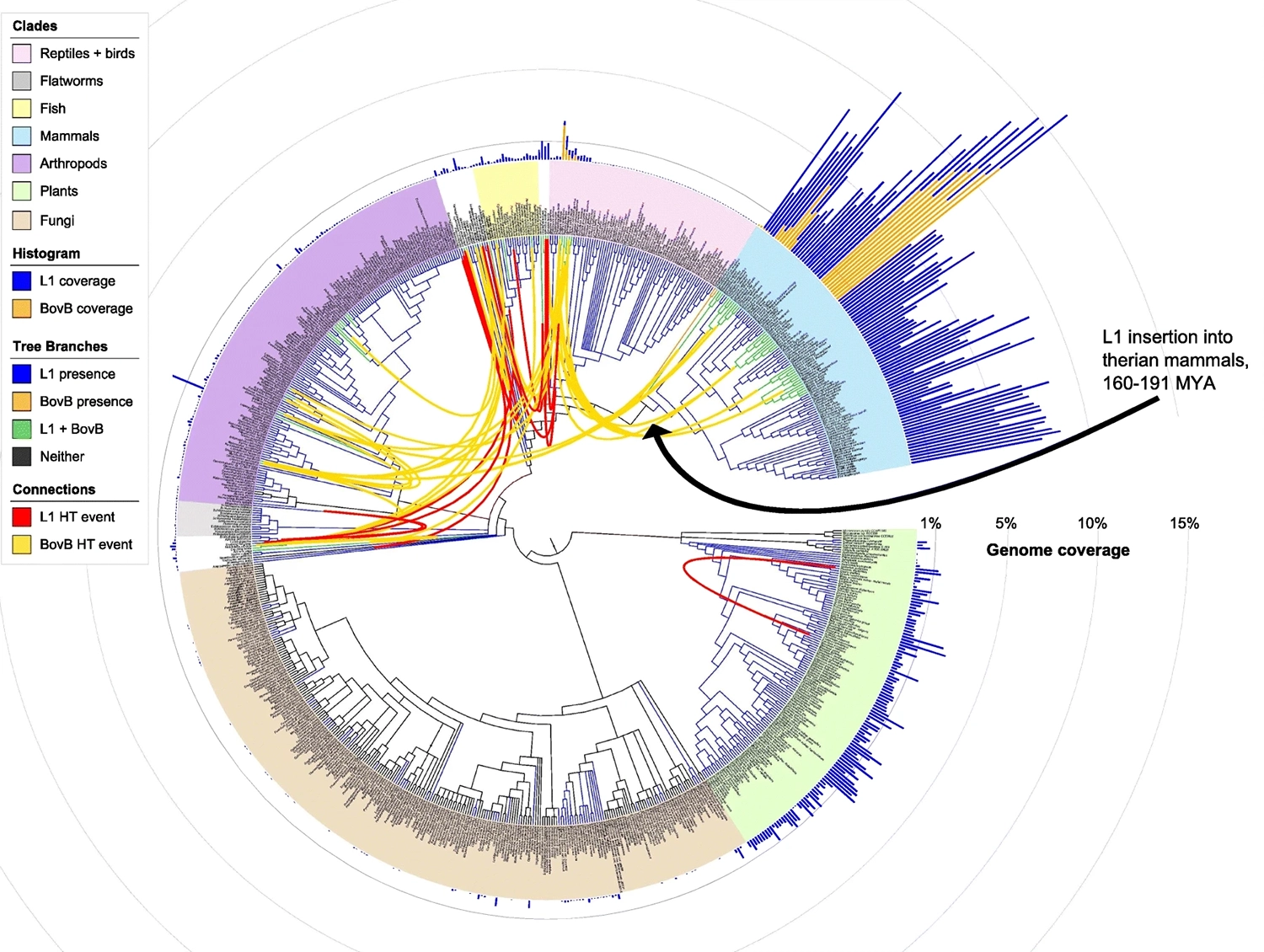

Perhaps this was life’s original motor: a primitive but quasi-stable metabolism, as yet without genes, enzymes, or even a clearly defined boundary between inside and outside. Such upgrades might have followed before long, though, for that chemical synthesis motor closely resembles the “reverse Krebs cycle,” now widely believed to have powered the earliest cells.

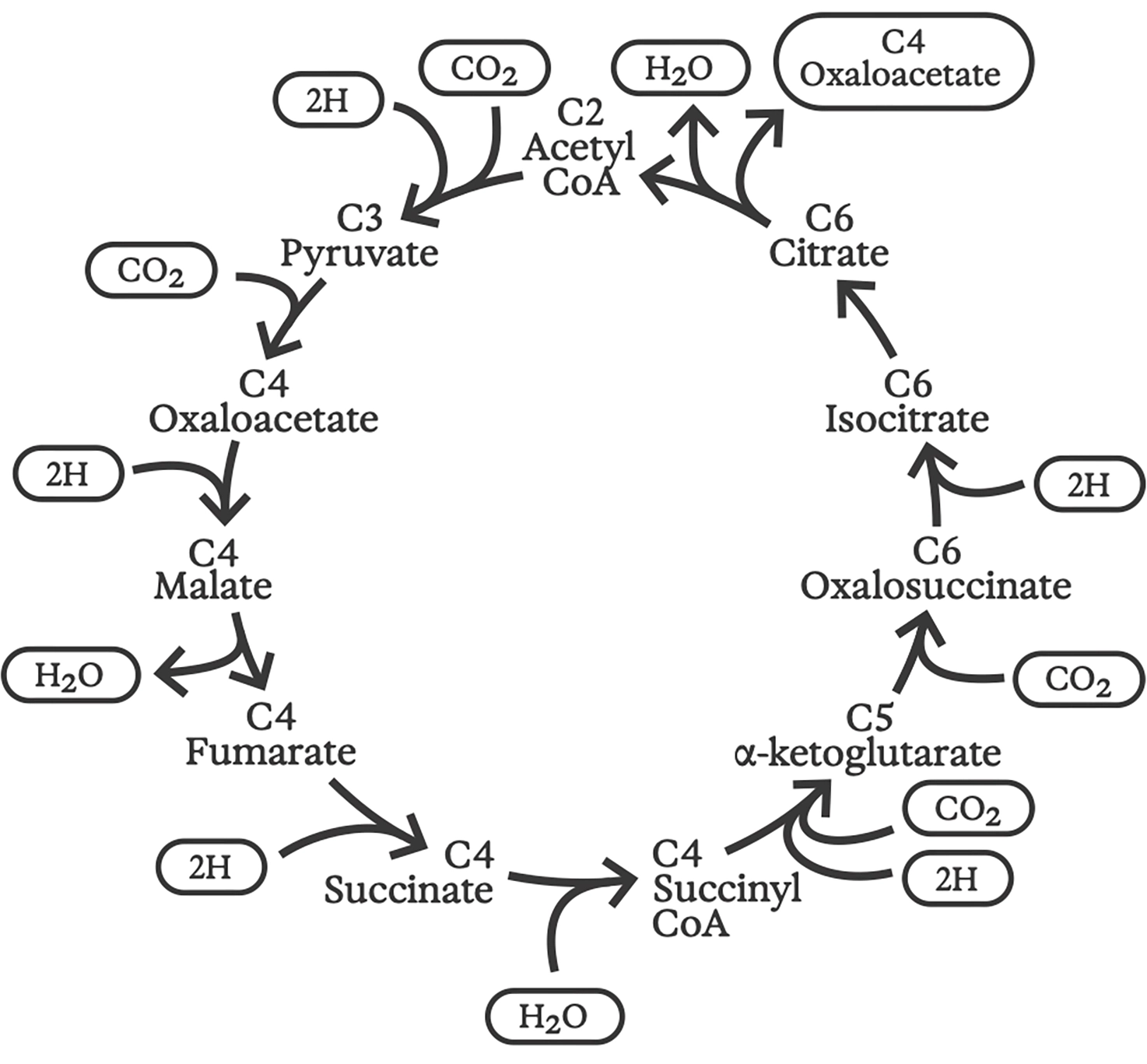

The ordinary or “forward” Krebs cycle was discovered in 1937 by groundbreaking biochemist Hans Krebs (1900–1981). More like a gas-powered generator than a motor, the Krebs cycle is at the heart of how all aerobic organisms on Earth “burn” organic fuels to release energy, a process known as “respiration.” 6 Inputs to this cycle of chemical reactions include complex organic molecules (which we eat) and oxygen (which we inhale); the “exhaust” contains carbon dioxide and water (which we exhale). The energy produced maintains proton gradients across folded-up membranes inside our mitochondria, and the flow of these protons goes on to power every other cellular function.

Krebs cycle

Reverse Krebs cycle

The idea of a “reverse Krebs cycle” was first proposed by a trio of researchers at UC Berkeley in 1966. 7 It remained controversial for decades, but is now known to power carbon fixation in ancient anaerobic sulfur bacteria—some of which still make their homes in deep-sea hydrothermal vents. 8 As its name implies, the reverse Krebs cycle consists of roughly the same chemical reactions as the forward cycle, but running in the opposite direction. Starting with water and carbon dioxide, proton gradients drive the synthesis of all of the basic building blocks needed for cellular structure and function, including sugars, amino acids for proteins, fatty acids and isoprenes for cell membranes, and nucleotides for building RNA and DNA. 9

X-ray of Russian matryoshka dolls

All life came from the sea, and the interior of every cell in every living organism reproduces that salty, watery environment—a tiny “ocean inside.” This much is common knowledge. But our mitochondria, the “power plants” within our cells where respiration takes place, may in fact be recapitulating the much more specific deep-sea chemistry of a black smoker. In an almost literal sense, our bodies are like Russian matryoshka dolls, membranes within membranes, and each nested environment recreates an earlier stage in the evolution of life on Earth.

The deeper inside ourselves we look, the farther we can see into the past. A beautiful, shivery thought.

Symbiogenesis

Whether RNA or metabolism came first, even the simplest bacteria surviving today are a product of many subsequent evolutionary steps. Yet unlike the everyday, incremental mutation and selection Darwin imagined, the most important of these steps may have been large and sudden. These “major evolutionary transitions” involve simpler, less complex replicating entities becoming interdependent to form a larger, more complex, more capable replicator. 10

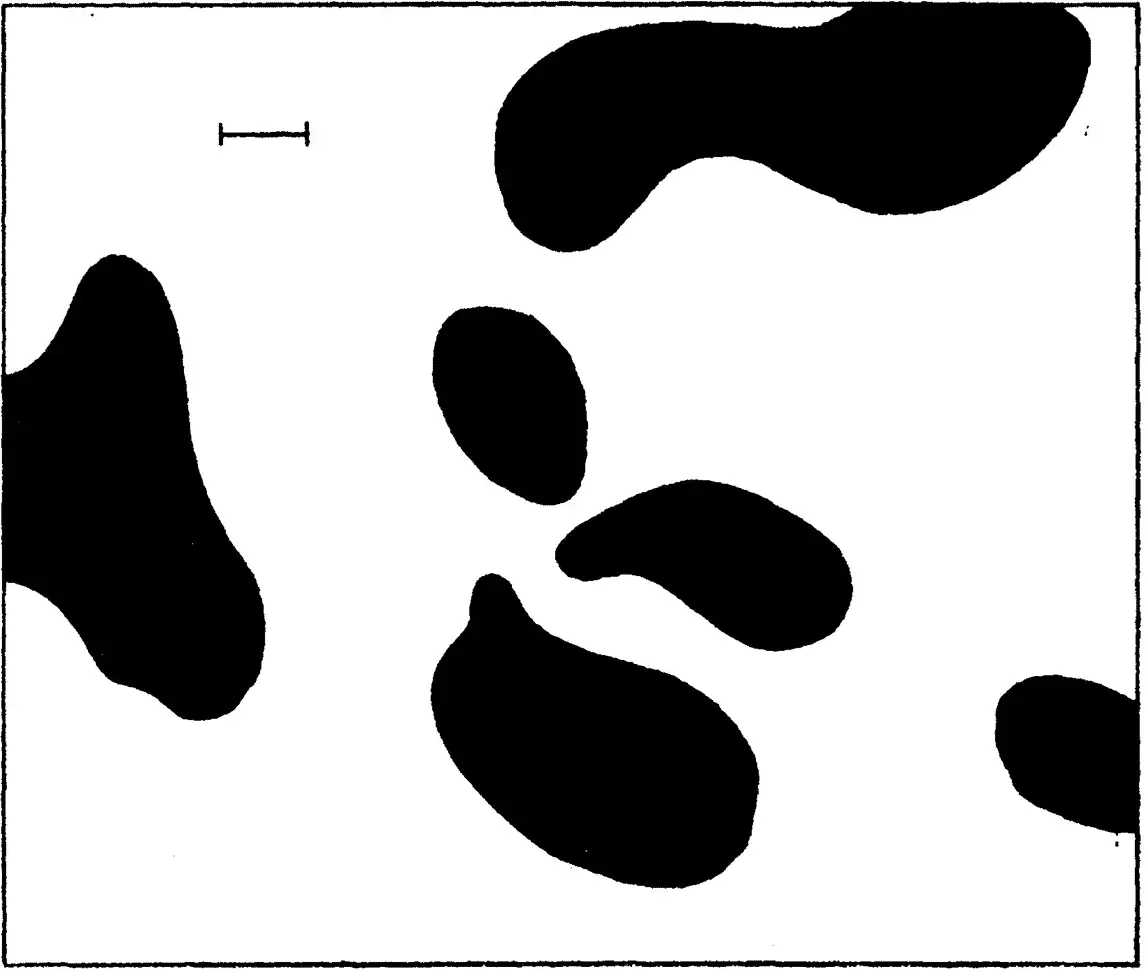

Transmission electron microscopy showing mitochondria in cells

As maverick biologist Lynn Margulis (1938–2011) discovered in the 1960s, eukaryotic cells, like those that make up our bodies, are the result of such an event. Roughly two billion years ago, the bacteria that became our mitochondria were engulfed by another single-celled life form 11 much like today’s archaea—tiny, equally ancient microorganisms that continue to inhabit extreme environments, like hot springs and deep-sea vents. This is “symbiogenesis,” the creation or genesis of a new kind of entity out of a novel “symbiosis,” or mutually beneficial relationship, among pre-existing entities.

At moments like these, the tree of life doesn’t just branch; it also entangles with itself, its branches merging to produce radically new forms. Margulis was an early champion of the idea that these events drive evolution’s leaps forward.

It’s likely that bacteria are themselves the product of such symbiotic events—for instance, between RNA and metabolism. 12 RNA could replicate without help from proteins, and the metabolic motor could proliferate without help from genes, but when these systems cooperate, they do better. The looping chemical-reaction networks in those black smokers can be understood as such an alliance in their own right, a set of reactions which, by virtue of catalyzing each other, can form a more robust, self-sustaining whole.

So in a sense, Darwin may have been right to say that “it is mere rubbish” to think about the origin of life, for life may have had no single origin, but rather, have woven itself together from many separate strands, the oldest of which look like ordinary chemistry. Intelligent design is not required for that weaving to take place; only the incontrovertible logic that sometimes an alliance creates something enduring, and that whatever is enduring … endures.

Often, enduring means both creating and occupying entirely new niches. Hence eukaryotes did not replace bacteria; indeed, they ultimately created many new niches for them. Likewise, the symbiotic emergence of multicellular life—another major evolutionary transition—did not supplant single-celled life. Like an ancient parchment overwritten by generations of scribes, our planet is a palimpsest, its many-layered past still discernible in the present. Even the black smokers, throwbacks to a Hadean sea billions of years ago, are still bubbling away in the depths. The self-catalyzing chemistry of proto-life may still be brewing down there, slowly, on the ocean floor.

The idea that evolution is driven by symbiotic mergers, the earliest of which preceded biology as we know it, has far-reaching implications. One is that the boundary between life and non-life is not well defined; symbiogenesis can involve any process that, one way or another, is self-perpetuating. Evolutionary dynamics are thus more like a physical law than a biological principle. Everything is subject to evolution, whether we consider it to be “alive” or not.

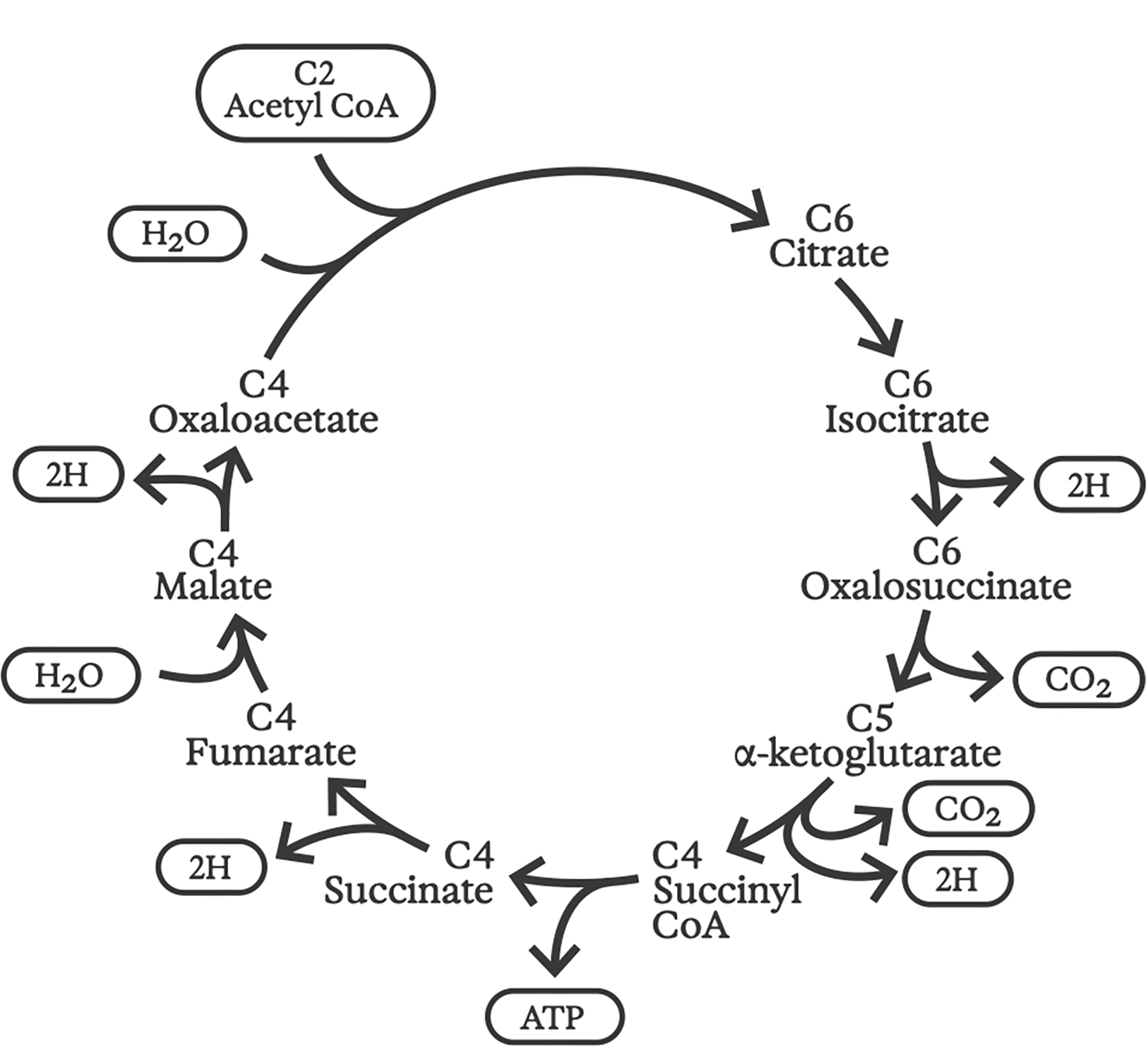

The symbiogenetic view also renders the idea of distinct species, classified according to a Linnaean taxonomy, somewhat ill-defined—or at best, of limited applicability. Such taxonomies assume that only branching takes place, not merging. Bacteria, which promiscuously transfer genes even between “species,” already challenge this idea. 13 Taxonomies break down entirely when we try to apply them to even more fluid situations, like the possible proto-life in black smokers, or microbiomes, or the more complex symbioses we’ll explore later.

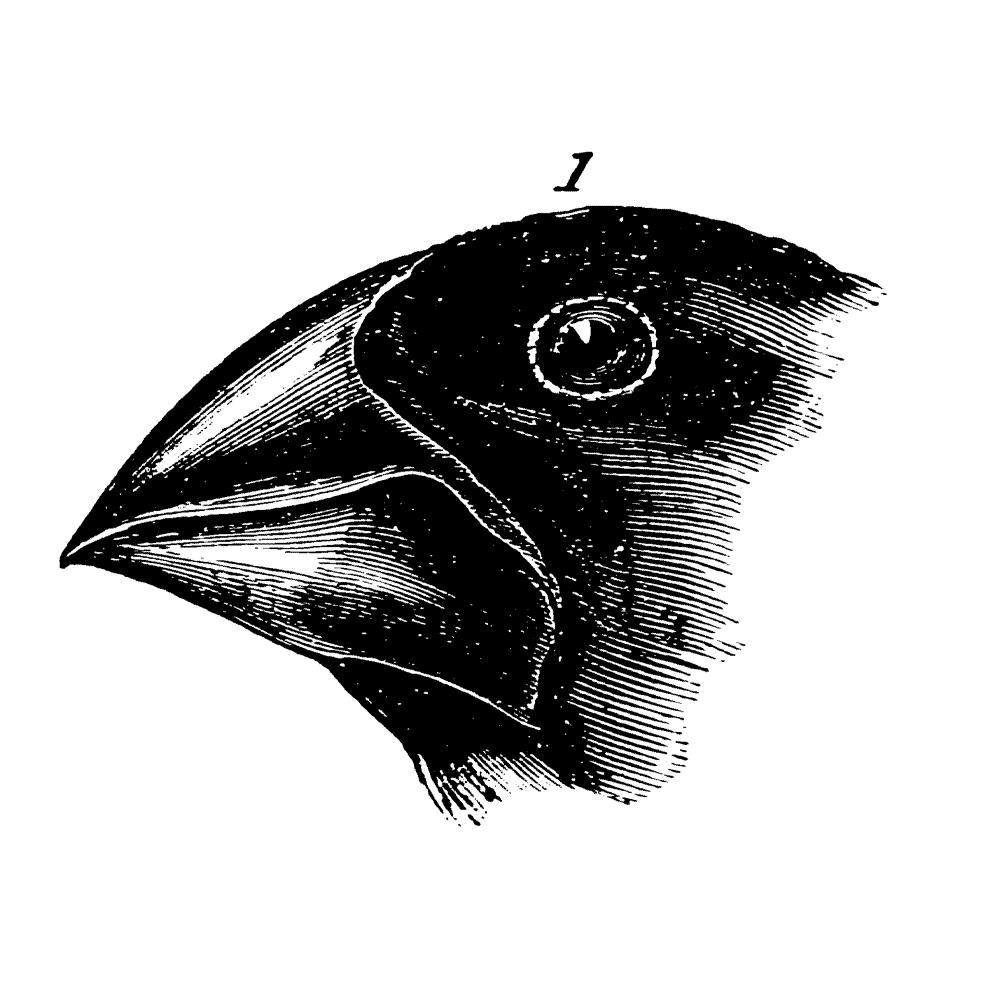

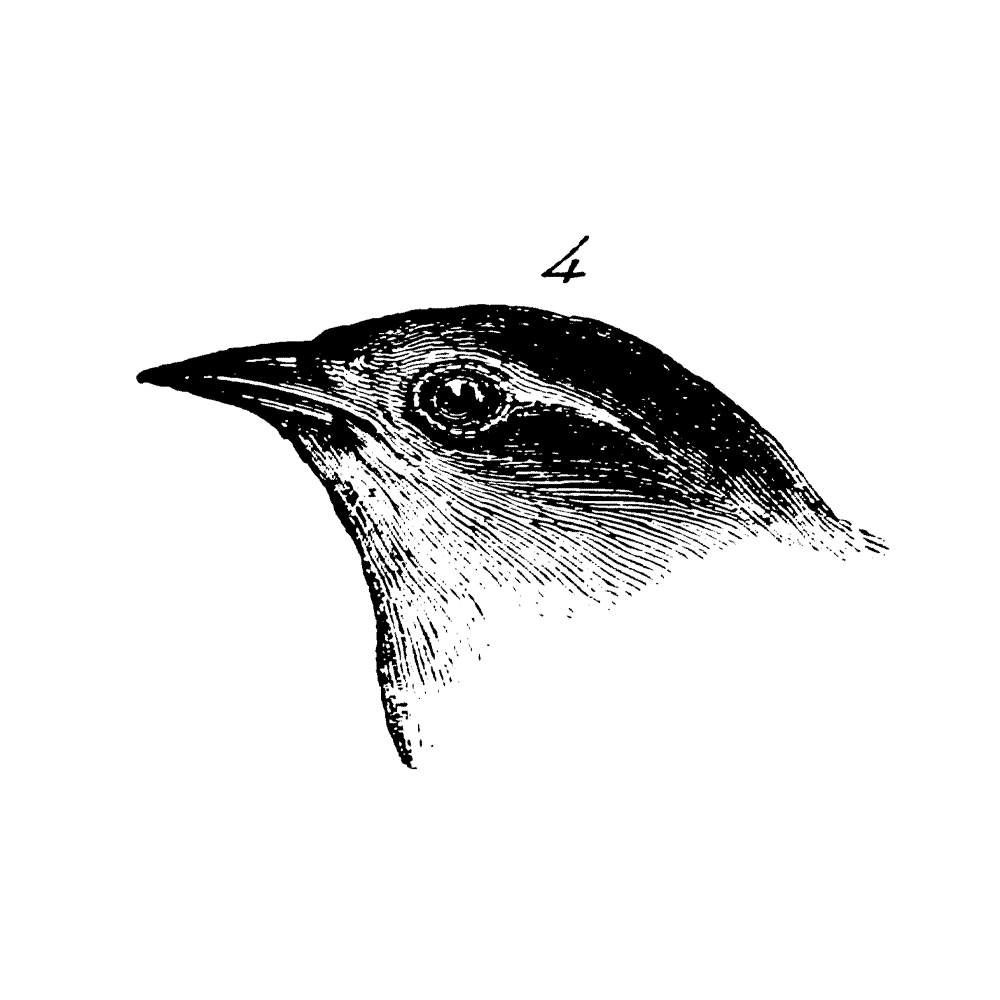

Galapagos finches, from Darwin, Voyage of the Beagle, 1845

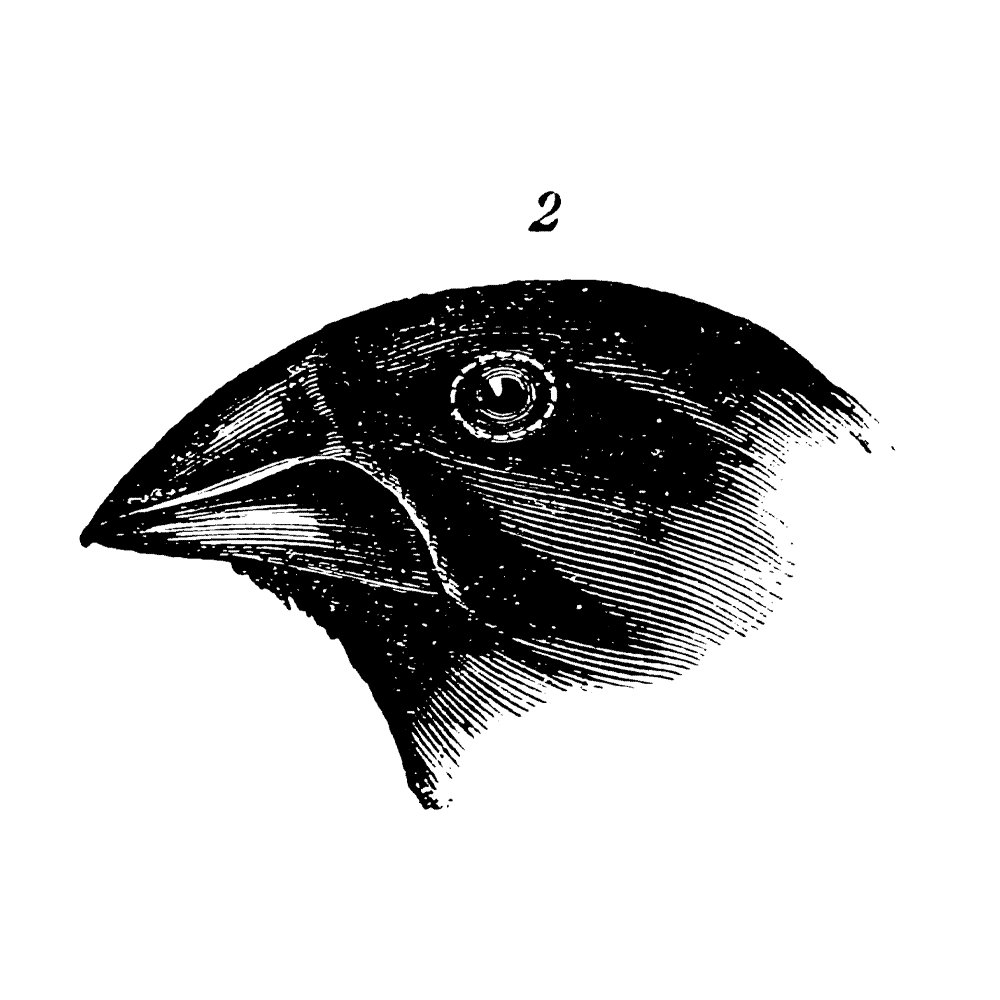

Galapagos finches, from Darwin, Voyage of the Beagle, 1845

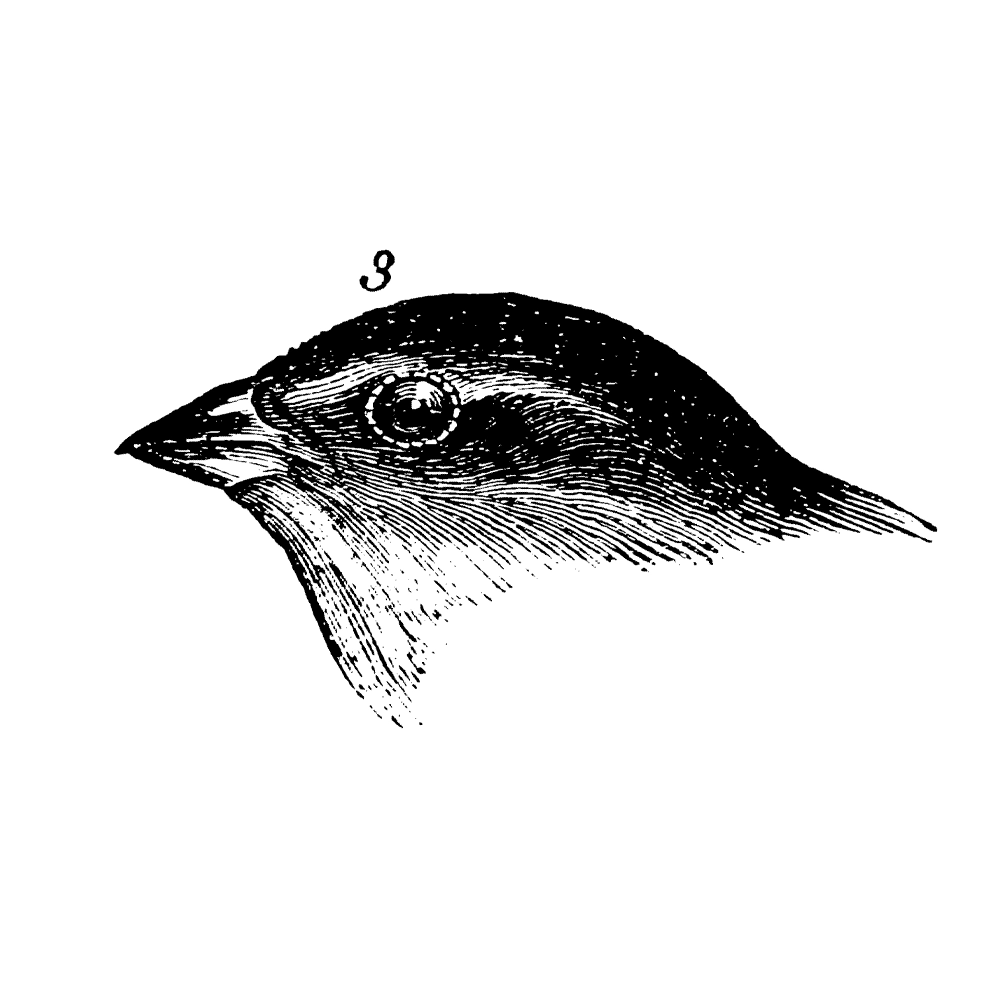

Galapagos finches, from Darwin, Voyage of the Beagle, 1845

Galapagos finches, from Darwin, Voyage of the Beagle, 1845

Perhaps most importantly, symbiogenesis explains evolution’s arrow of time, as classical Darwinian theory alone cannot. When life branches, specializing to adapt to a niche—like Darwin’s finches with their differently shaped beaks, each optimized for a specific food source—those branches are in general no more complex than their ancestral form. This has led some classical evolutionary theorists to argue that the increasing complexity of life on Earth is an anthropocentric illusion, nothing more than the result of a random meander through genetic possibilities. 14 Relatedly, one sometimes hears the claim that since all extant species are of equal age—as it seems they must be, since all share a common single-celled ancestor some four billion years ago—no species is more “evolved” than any other.

On its face, that seems reasonable. But as we’ve seen, classical Darwinian theory struggles to explain why life seems to become increasingly complex, or, indeed, how life could arise in the first place. In themselves, random changes or mutations can only fine-tune, diversify, and optimize, allowing the expression of one or another variation already latent in the genetic space. (The space of possible finch beaks, for instance.)

When one prokaryote ends up living inside another, though, or multiple cells band together to make a multicellular life form, the resulting composite organism is clearly more complex than its parts. Something genuinely new has arisen. The branching and fine-tuning of classical evolution can now start to operate on a whole different level, over a new space of combinatorial possibilities.

Classical evolution isn’t wrong; it just misses half of the story—the more rapid, more creative half. One could say that evolution’s other half is revolution, and that revolutions occur through symbiosis.

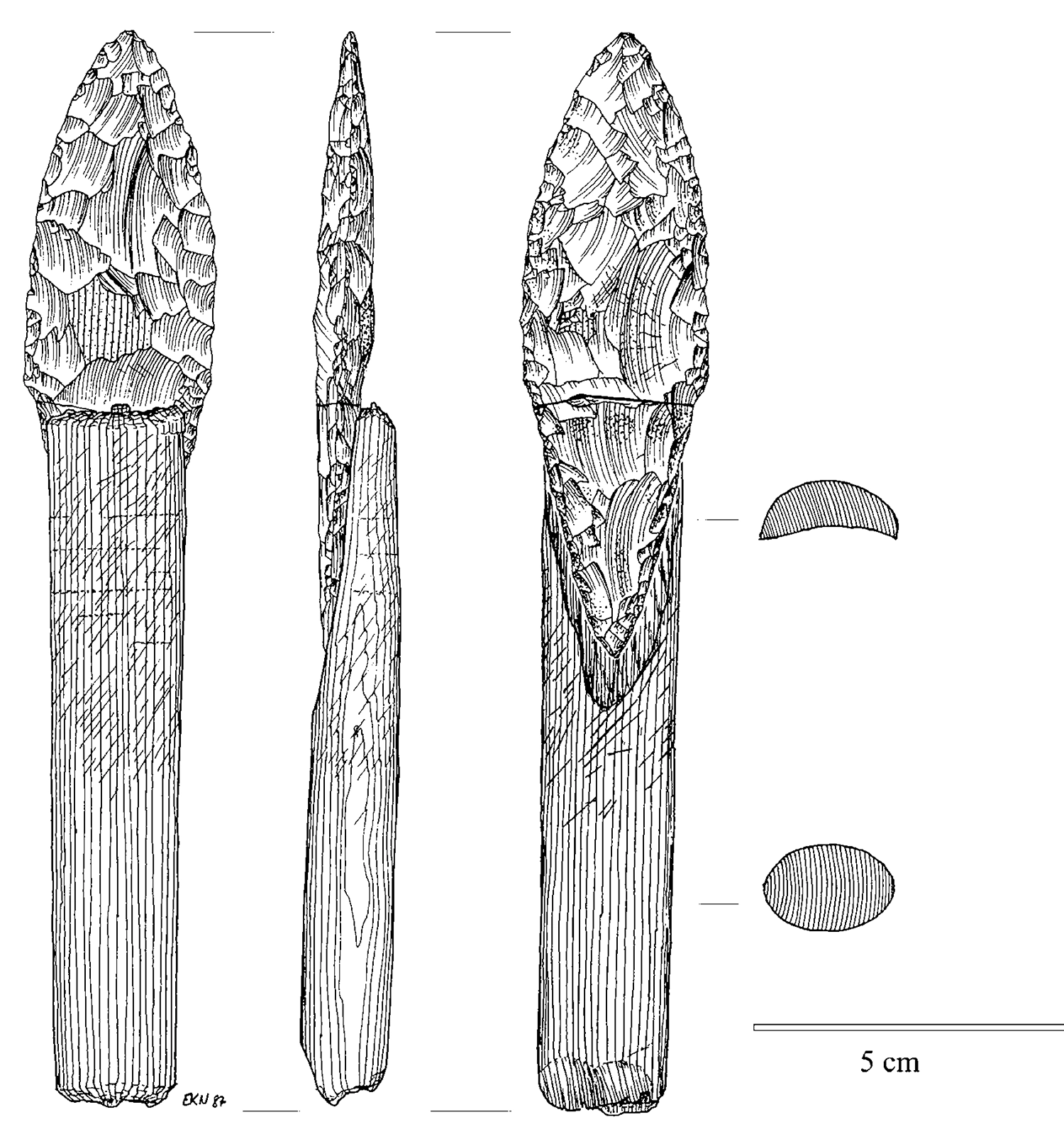

Suggestively, the same is true of technology. In Paleolithic times, a hafted spear was not just a specialized stone point, but something new that arose by combining at least three parts: a stone point, a shaft, and something like sinew to bind them. This, too, opened up a new combinatorial design space. Or, in more recent times, the silicon chip was not just an evolved transistor; it was something new that could be made by putting multiple transistors together on the same die. One doesn’t arrive at chip design merely by playing with the design parameters of an individual transistor.

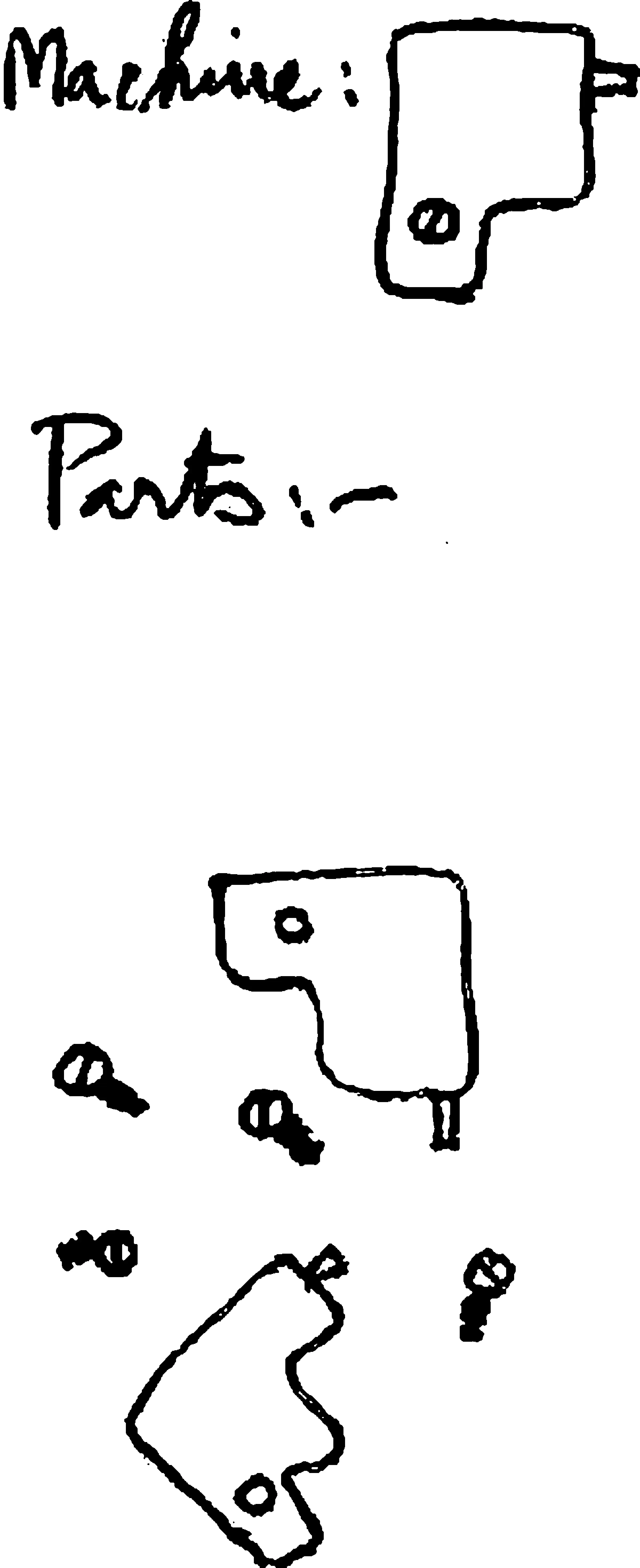

Hafted spear point from the mid-Holocene Arctic Small Tool site of Qeqertasussuk, West Greenland. Drawn by Eva Koch, reproduced with permission of Bjarne Grønnow.

That’s why evolution progresses from simpler to more complex forms. It’s also why the simpler forms often remain in play even after a successful symbiogenetic event. Standalone stone points, like knives and hand axes, were still being made after the invention of the hafted spear; and, of course, spearheads themselves still count as stone points. 15 Moreover, no matter how recently any particular stone point was made, we can meaningfully talk about stone points being “older” as a category than spears. Spears had to arise later, because their existence depended on the pre-existence of stone points.

It’s equally meaningful to talk about ancient life forms, like bacteria and archaea, co-existing alongside recent and far more complex ones, like humans—while recognizing that humans are, in a sense, complex colonies of bacteria and archaea that have undergone a cascade of symbiotic mergers.

Reproductive Functions

While most biochemists have focused on understanding the particular history and workings of life on Earth, a more general understanding of life has come from an unexpected quarter: computer science. The theoretical foundations of this surprising connection date back to those two founding figures of the field, Alan Turing and John von Neumann.

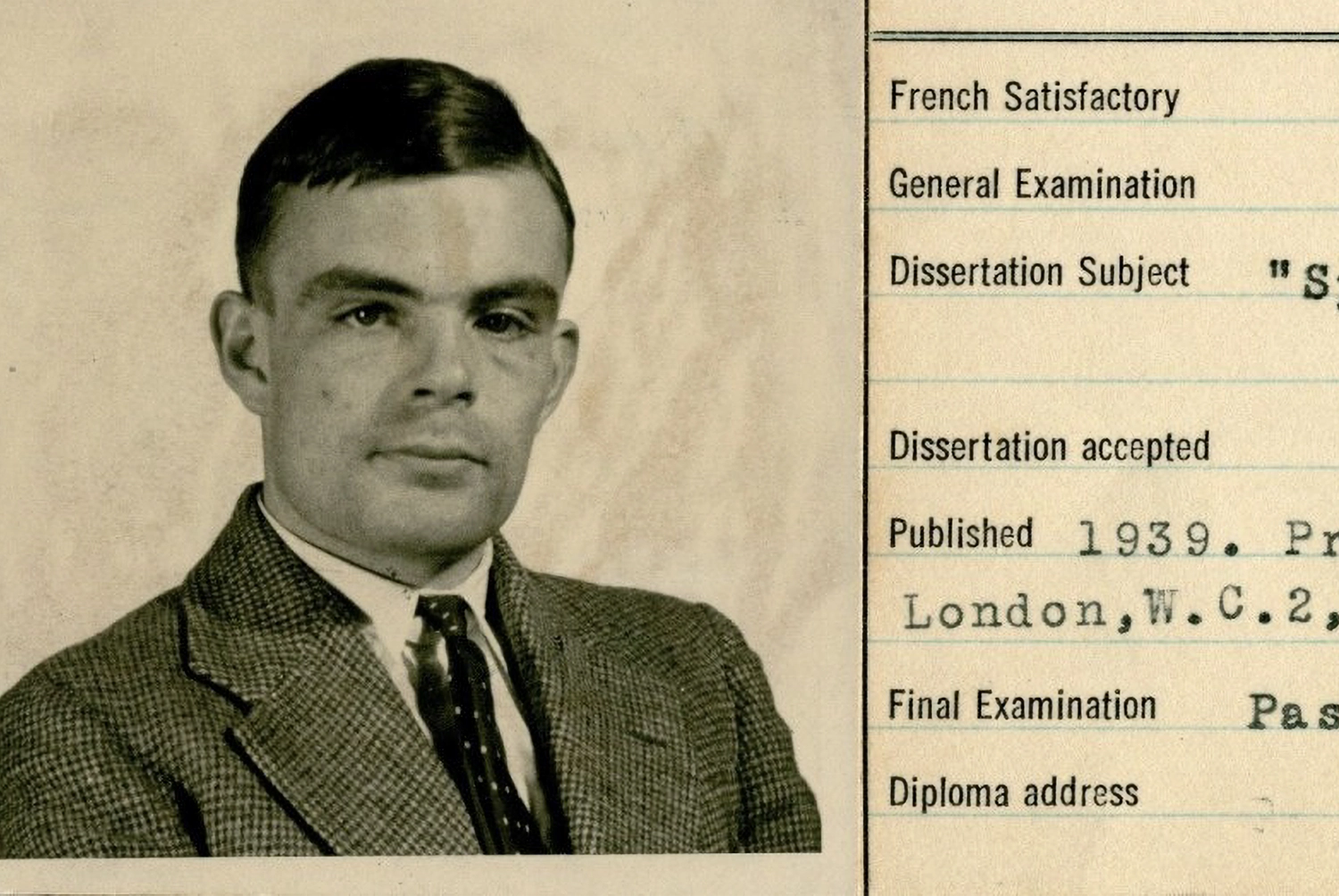

Alan Turing at Princeton University

I’ve already mentioned Turing’s 1950 paper introducing the Imitation Game or Turing Test, but his first great contribution came fifteen years earlier. After earning an undergraduate degree in mathematics at Cambridge in 1935, Turing focused on one of the fundamental outstanding problems of the day: the Entscheidungsproblem (German for “decision problem”), which asked whether there exists an algorithm for determining the validity of an arbitrary mathematical statement.

The answer turned out to be “no,” but the way Turing went about proving it ended up being far more important than the result itself—which was lucky, since American mathematician Alonzo Church had just scooped Turing, publishing his own proof a few months earlier using a different approach. 16 After corresponding with him about the Entscheidungsproblem, Turing would end up moving to Princeton to become Church’s doctoral student.

Proving mathematical statements about mathematical statements requires defining a general notation for such statements, and a procedure for evaluating them. Church did so using mathematical symbols, especially the lowercase Greek letter λ (lambda), thus inventing a self-referential “lambda calculus.”

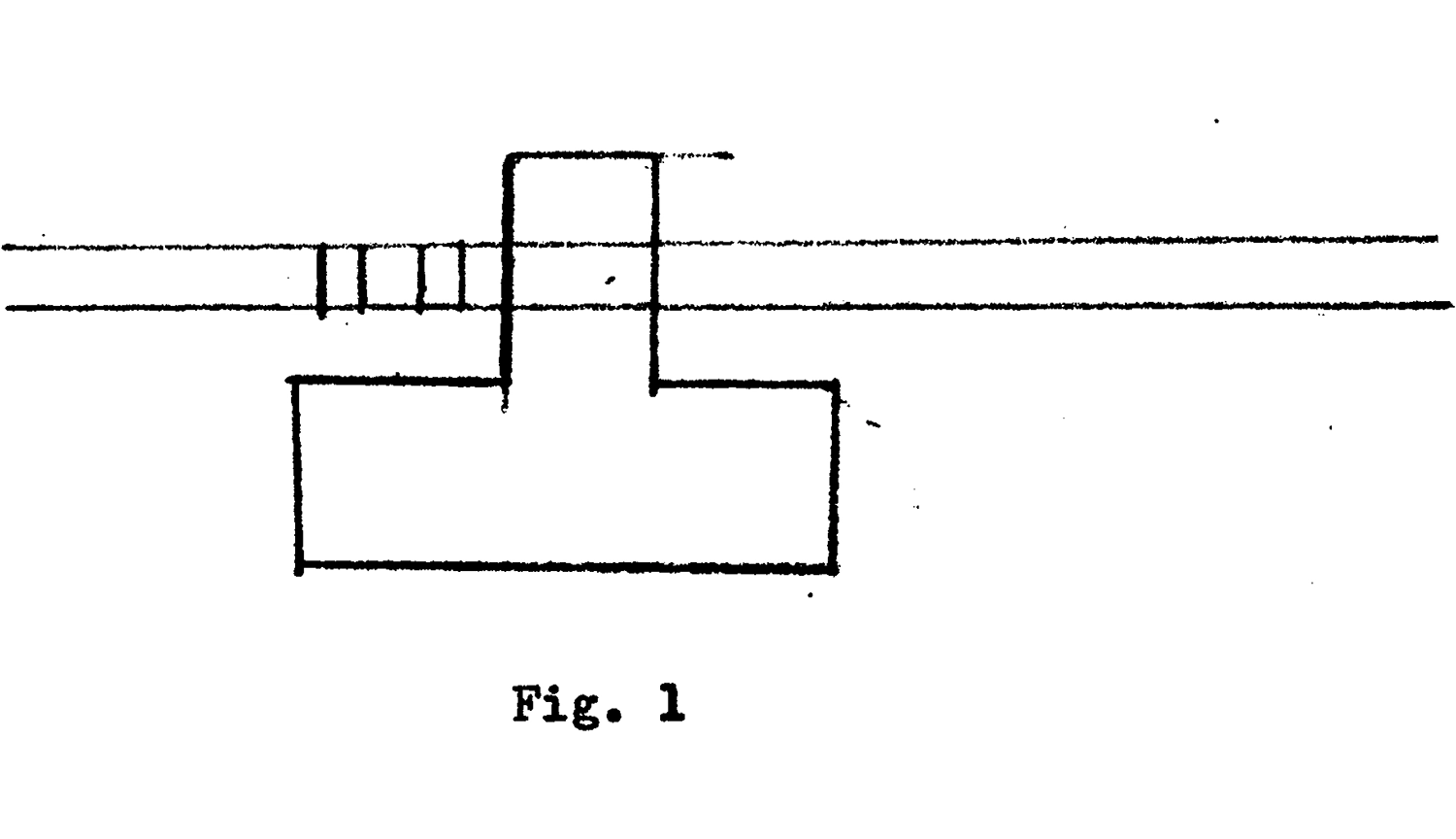

Von Neumann illustrates a Turing machine at the start of his third 1945 lecture on high-speed computing machines

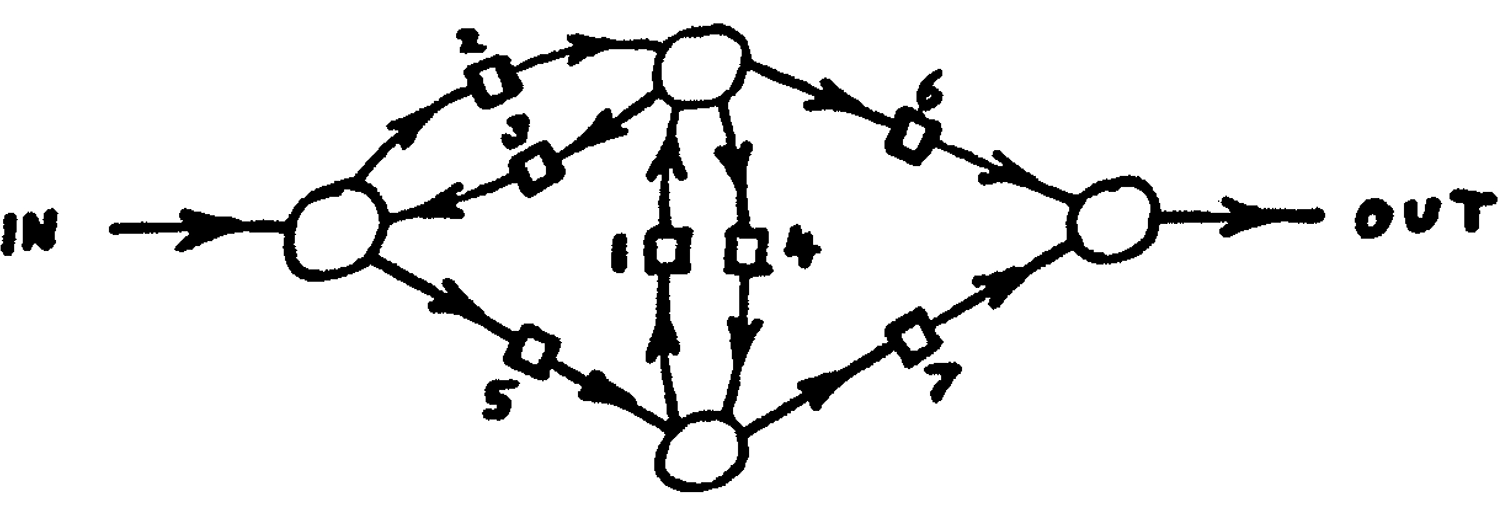

Turing took a less conventional route. His procedure involved an imaginary gadget we now call the “Turing Machine.” The Turing Machine consists of a read/write head, which can move left or right along an infinite tape, reading and writing symbols on the tape according to a set of rules specified by a built-in table.

First, Turing showed that such a machine could do any calculation or computation that can be done by hand, given an appropriate table of rules, enough time, and enough tape. He suggested a notation for writing down the table of rules, which he referred to as a machine’s “Standard Description” or “S. D.” Today, we’d call it a “program.”

Then, the really clever part: if the program itself is written on the tape, there exist particular tables of rules that will read the program and perform whatever computation it specifies. Today, these are called “Universal Turing Machines.” In Turing’s more precise language, “It is possible to invent a single machine which can be used to compute any computable sequence. If this machine U is supplied with a tape on the beginning of which is written the S. D. of some computing machine M, then U will compute the same sequence as M.”

John von Neumann’s Los Alamos ID badge photo, 1940s

Some programs run for a time, then finish. Others run forever. Since a Universal Turing Machine allows programs themselves to be expressed as values on the tape, a program can take another program as input. One can imagine such a “meta-program” outputting a single bit of information that denotes whether the inputted program will eventually finish, or will keep running forever. Turing called this the “halting problem.” In his 1936 paper, he proved that a program that solves the halting problem for all possible input programs—and that is itself guaranteed to halt—is a logical impossibility. This was the result that answered the Entscheidungsproblem in the negative.

More consequentially, though, the Universal Turing Machine defined a generic procedure for computation. Turing was soon able to prove that any function that could be computed by his imaginary machine could also be expressed in Church’s lambda calculus, and vice versa 17 —a cornerstone of the idea now known as the Church-Turing thesis: that computability is a universal concept, regardless of how it’s done.

In the early 1940s, John von Neumann, a Hungarian American polymath who had already made major contributions to physics and mathematics, turned his attention to computing. He became a key figure in the design of the ENIAC and EDVAC—among the world’s first real-life Universal Turing Machines, now known simply as “computers.” 18

Turning an imaginary mathematical machine into a working physical one required many further conceptual leaps, in addition to a lot of hard nuts-and-bolts engineering. For instance, over the years, much creativity has gone into figuring out how simple the “Standard Description” of a Universal Turing Machine can get. Only a few instructions are needed. Esoteric language nerds have even figured out how to compute with a single instruction (a so-called OISC or “one-instruction set computer”).

There are irreducible requirements, though: the instruction, or instructions, must change the environment in some way that subsequent instructions are able to “see,” and there must be “conditional branching,” meaning that depending on the state of the environment, either one thing or another will happen. In most programming languages, this is expressed using “if/then” statements. When there’s only a single instruction, it must serve both purposes, as with the SUBLEQ language, whose only instruction is “subtract and branch if the result is less than or equal to zero.”

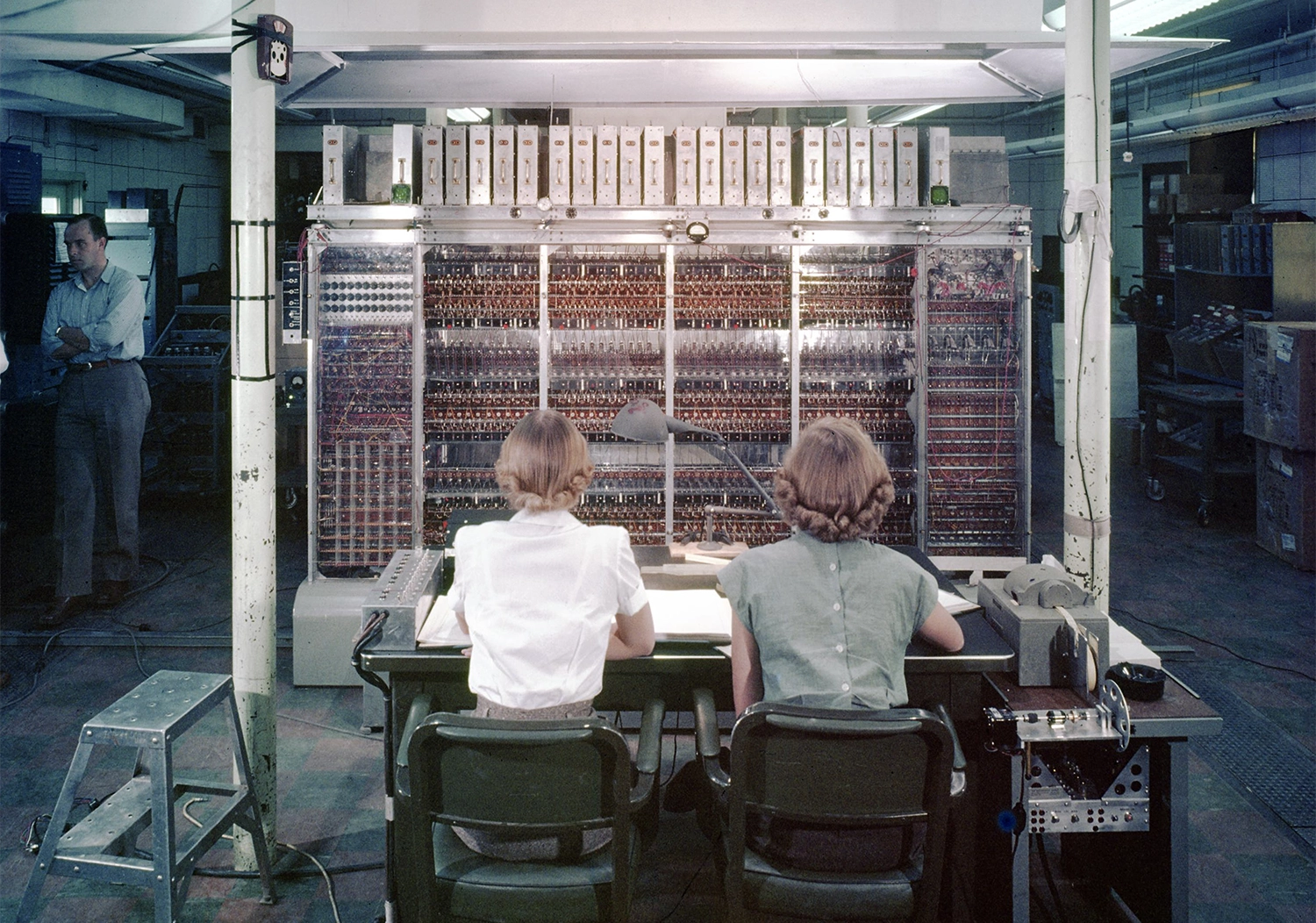

Programmers in front of the MANIAC computer, Los Alamos National Lab, 1952

Both Turing and von Neumann were keenly aware of the parallels between computers and brains. Von Neumann’s report on the EDVAC explicitly described the machine’s basic building blocks, its “logic gates,” as electronic neurons. 19 Whether or not that analogy held (as we’ll see, it did not; neurons are more complex than logic gates), his key insight was that both brains and computers are defined not by their mechanisms, but by what they do—their function, in both the colloquial and mathematical sense.

In real life, though, the brain is not an abstract machine, but part of the body, and the body is part of the physical world. How can one speak in purely computational terms about the function of a living organism, when it must physically grow and reproduce?

Although working independently, toward the end of their lives, Turing and von Neumann both became captivated by the connection between biology and computation. 20 Turing did pioneering work in “morphogenesis,” working out how cells could use chemical signals, which he dubbed “morphogens,” to form complex self-organizing patterns—the key to multicellularity. 21 Although computers were still too primitive to carry out any detailed simulations of such systems, he showed mathematically how so-called “reaction-diffusion” equations could generate spots, like those on leopards and cows, or govern the growth of tentacles, like those of the freshwater polyp, Hydra. 22

Reaction–diffusion pattern from Turing, “The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis,” 1952

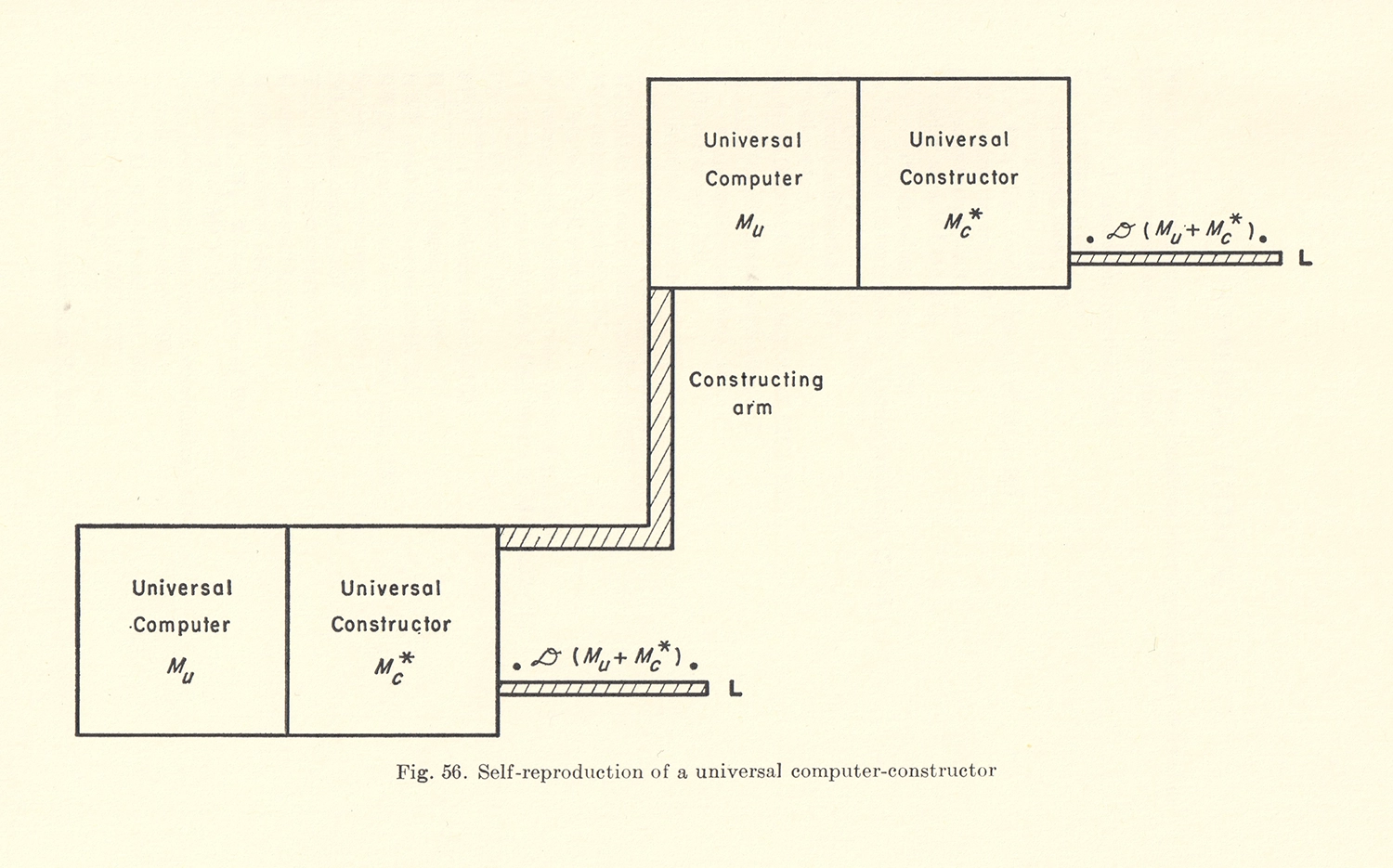

Around the same time, in a 1951 paper, 23 von Neumann imagined a machine made of standardized parts, like Lego bricks, paddling around on a reservoir where those parts could be found bobbing on the water. The machine’s job was to gather all of the needed parts and construct another machine like itself. Of course, that’s exactly what a bacterium does to reproduce; in fact it’s what every cell must do to divide, and what every mother must do to give birth.

Note on self-reproducing machinery from the notebook of cybernetics pioneer W. Ross Ashby, December 22, 1954

It’s possible for a trivially simple structure, like a seed crystal, to “reproduce” merely by acting as a template for more of the same stuff to crystallize around it. But a complex machine—one with any internal parts, for example—can’t serve as its own template. And if you are a complex machine, then, on the face of it, manufacturing something just as complex as you yourself are has a whiff of paradox, like lifting yourself up by your own bootstraps. However, von Neumann showed that it is not only possible, but straightforward, using a generalization of the Universal Turing Machine.

He envisioned a “machine A” that would read a tape containing sequential assembly instructions based on a limited catalog of parts, and carry them out, step by step. Then a “machine B” would copy the tape—assuming the tape itself was also made of available parts. If instructions for building machines A and B are themselves encoded on the tape, then voilà—you would have a replicator. 24

Instructions for building any additional non-reproductive machinery could also be encoded on the tape, so it would even be possible for a replicator to build something more complex than itself. 25 A seed, or a fertilized egg, illustrates the point. Even more fundamentally, encoding the instructions to build oneself in a form that is itself replicated (the tape) is the key to open-ended evolvability, meaning the ability for evolution to select for an arbitrary design change, and for that change to be inherited by the next generation.

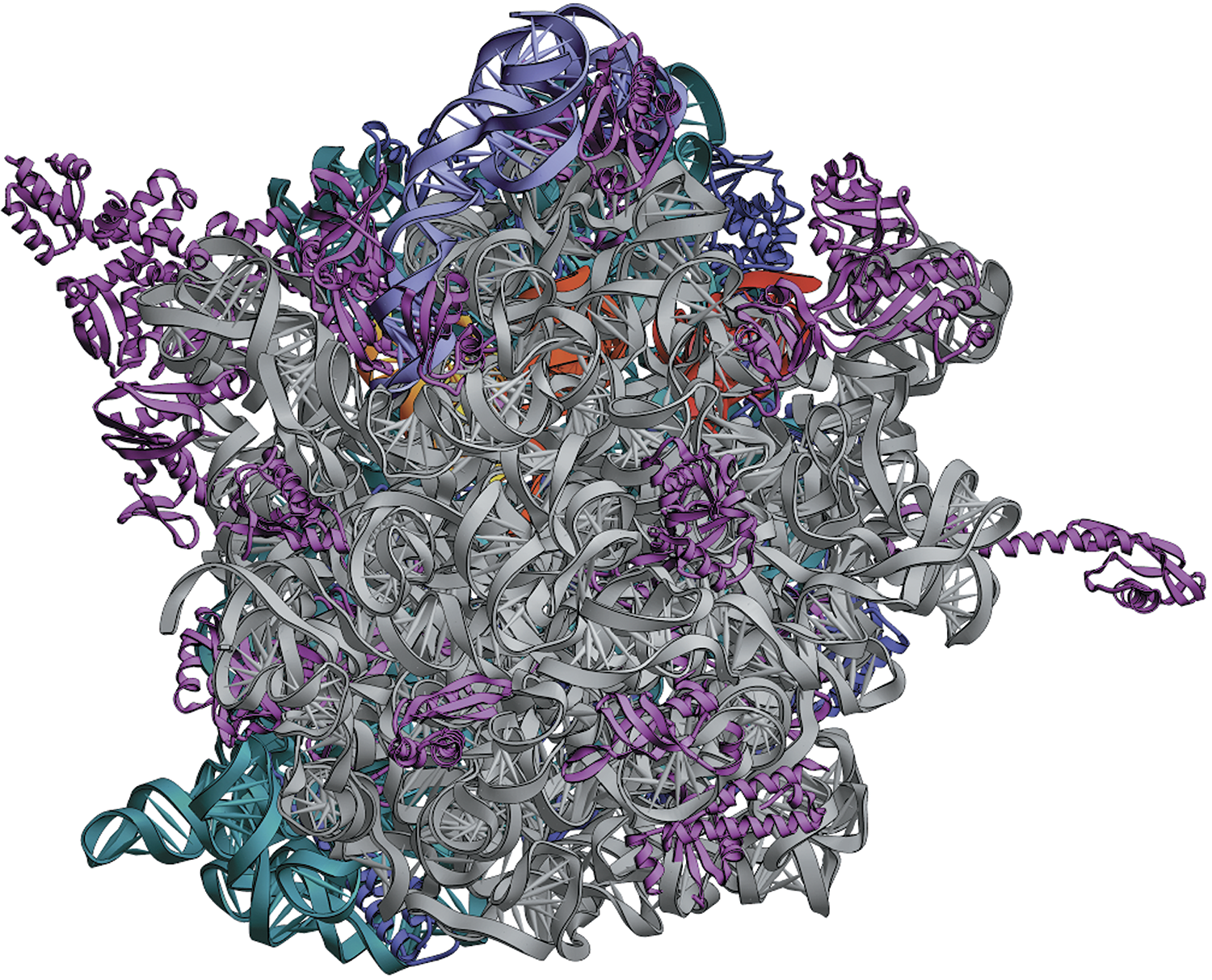

Remarkably, von Neumann described these requirements for an evolvable, self-replicating machine before the discovery of DNA’s structure and function. 26 Nonetheless, he got it exactly right. For life on Earth, DNA is the tape; DNA polymerase, which copies DNA, is “machine B”; and ribosomes, which build proteins by following the sequentially encoded instructions on DNA, are “machine A.” Ribosomes and DNA polymerase are made of proteins whose sequences are, in turn, encoded in our DNA and manufactured by ribosomes. That is how life lifts itself up by its own bootstraps.

Life as Computation

Although this is seldom fully appreciated, von Neumann’s insight established a profound link between life and computation. Remember, machines A and B are Turing Machines. They must execute instructions that affect their environment, and those instructions must run in a loop, starting at the beginning and finishing at the end. That requires branching, such as “if the next instruction is the codon CGA then add an arginine to the protein under construction,” and “if the next instruction is UAG then STOP.” It’s not a metaphor to call DNA a “program”—that is literally the case.

Of course, there are meaningful differences between biological computing and the kind of digital computing done by the ENIAC or your smartphone. DNA is subtle and multilayered, including phenomena like epigenetics and gene proximity effects. Cellular DNA is nowhere near the whole story, either. Our bodies contain (and continually swap) countless bacteria and viruses, each running their own code.

Structure of the 70S ribosome

Biological computing is “massively parallel,” decentralized, and noisy. Your cells have somewhere in the neighborhood of three hundred quintillion ribosomes, all working at the same time. Each of these exquisitely complex floating protein factories is, in effect, a tiny computer—albeit a stochastic one, meaning not entirely predictable. The movements of hinged components, the capture and release of smaller molecules, and the manipulation of chemical bonds are all individually random, reversible, and inexact, driven this way and that by constant thermal buffeting. Only a statistical asymmetry favors one direction over another, with clever origami moves tending to “lock in” certain steps such that a next step becomes likely to happen. This differs greatly from the operation of logic gates in a computer, which are irreversible, 27 and designed to be ninety-nine point many-nines percent reliable and reproducible.

Biological computing is computing, nonetheless. And its use of randomness is a feature, not a bug. In fact, many classic algorithms in computer science also require randomness (albeit for different reasons), which may explain why Turing insisted that the Ferranti Mark I, an early computer he helped to design in 1951, include a random number instruction. 28 Randomness is thus a small but important conceptual extension to the original Turing Machine, though any computer can simulate it by calculating deterministic but random-looking or “pseudorandom” numbers.

Turing (right) at the console of the Ferranti Mark II computer

Parallelism, too, is increasingly fundamental to computing today. Modern AI, for instance, depends on both massive parallelism and randomness—as in the parallelized “stochastic gradient descent” (SGD) algorithm, used for training most of today’s neural nets, the “temperature” setting used in chatbots to introduce a degree of randomness into their output, and the parallelism of Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), which power most AI in data centers.

Traditional digital computing, which relies on the centralized, sequential execution of instructions, was a product of technological constraints. The first computers needed to carry out long calculations using as few parts as possible. Originally, those parts were flaky, expensive vacuum tubes, which had a tendency to burn out and needed frequent replacement by hand. The natural design, then, was a minimal “Central Processing Unit” (CPU) operating on sequences of bits ferried back and forth from an external memory. This has come to be known as the “von Neumann architecture.”

Turing’s illustration of an “unorganized machine” (or neural network) from “Intelligent Machinery,” 1948

Turing and von Neumann were both aware that computing could be done by other means, though. Turing’s model of morphogenesis was a biologically inspired form of massively parallel, distributed computation. So was his earlier concept of an “unorganized machine,” a randomly connected neural net modeled after an infant’s brain. 29 These were visions of what computing without a central processor could look like—and what it does look like, in living systems.

Von Neumann also began exploring massively parallel approaches to computation as far back as the 1940s. In discussions with Polish mathematician Stanisław Ulam at Los Alamos, he conceived the idea of “cellular automata,” pixel-like grids of simple computational units, all obeying the same rule, and all altering their states simultaneously by communicating only with their immediate neighbors. With characteristic bravura, von Neumann went so far as to design, on paper, the key components of a self-reproducing cellular automaton, including a horizontal line of cells comprising a “tape” and blocks of cellular “circuitry” implementing machines A and B.

Von Neumann’s universal constructor arm from Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata, 1967

Designing a cellular automaton is far harder than ordinary programming, because every cell or “pixel” is simultaneously altering its own state and its environment. When that kind of parallelism operates on many scales at once, and is combined with randomness and subtle feedback effects, as in biological computation, it becomes even harder to reason about, “program,” or “debug.”

Nonetheless, we should keep in mind what these two pioneers understood so clearly: computing doesn’t have to be done with a central processor, logic gates, binary arithmetic, or sequential programs. One can compute in infinitely many ways. Turing and his successors have shown that they are all equivalent, one of the greatest accomplishments of theoretical computer science.

This “platform independence” or “multiple realizability” means that any computer can emulate any other one. If the computers are of different designs, though, the emulation may run s … l … o … w … l … y. For instance, von Neumann’s self-reproducing cellular automaton has never been physically built—though that would be fun to see! It was only emulated for the first time in 1994, nearly half a century after he designed it. 30

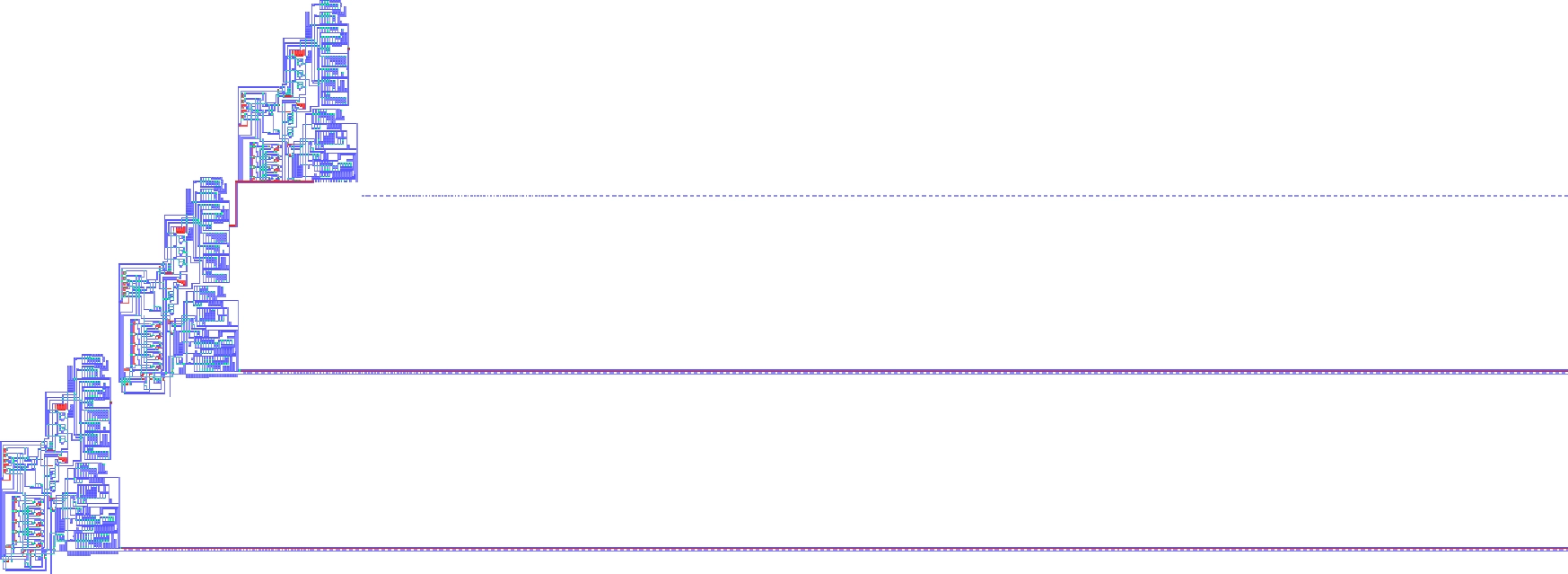

Implementation of von Neumann’s self-reproducing cellular automaton, Pesavento 1995. The second generation has nearly finished constructing the third (lines running off to the right are instruction tapes, much longer than shown).

It couldn’t have happened much earlier. A serial computer requires serious processing power to loop through the automaton’s 6,329 cells over the sixty-three billion time steps required for the automaton to complete its reproductive cycle. Onscreen, it worked as advertised: a pixelated two-dimensional Rube Goldberg machine, squatting astride a 145,315 cell–long instruction tape trailing off to the right, pumping information out of the tape and reaching out with a “writing arm” to slowly print a working clone of itself just above and to the right of the original.

It’s similarly inefficient for a serial computer to emulate a parallel neural network, heir to Turing’s “unorganized machine.” Consequently, running big neural nets like those in Transformer-based chatbots has only recently become practical, thanks to ongoing progress in the miniaturization, speed, and parallelism of digital computers.

In 2020, my colleague Alex Mordvintsev devised a clever combination of modern neural nets, Turing’s morphogenesis, and von Neumann’s cellular automata. Alex’s creation, the “neural cellular automaton” (NCA), replaces the simple per-pixel rule of a classic cellular automaton with a neural net. 31 This net, capable of sensing and affecting a few values representing local morphogen concentrations, can be trained to “grow” any desired pattern or image, not just zebra stripes or leopard spots.

A neural cellular automaton that generates (or re-generates) a lizard emoji, from Mordvintsev et al. 2020

Real cells don’t literally have neural nets inside them, but they do run highly evolved, nonlinear, and purposive “programs” to decide on the actions they will take in the world, given external stimulus and an internal state. NCAs offer a general way to model the range of possible behaviors of cells whose actions don’t involve movement, but only changes of state (here, represented as color) and the absorption or release of chemicals.

The first NCA Alex showed me was of a lizard emoji, which could regenerate not only its tail, but also its limbs and head! It was a powerful demonstration of how complex multicellular life can “think locally” yet “act globally,” even when each cell (or pixel) is running the same program—just as each of your cells is running the same DNA.

This was our first foray into the field known today as “artificial life” or “ALife.”

Artificial Life

Von Neumann’s work on self-reproducing automata shows us that, in a universe whose physical laws do not allow for computation, it would be impossible for life to evolve. Luckily, the physics of our universe do allow for computation, as proven by the fact that we can build computers—and that we’re here at all.

Now we’re in a position to ask: in a universe capable of computation, how often will life arise? Clearly, it happened here. Was it a miracle, an inevitability, or somewhere in between?

A few collaborators and I set out to explore this question in late 2023. 32 Our first experiments used an esoteric programming language invented thirty years earlier by a Swiss physics student and amateur juggler, Urban Müller. I’m afraid he called this language … Brainfuck. Please direct all naming feedback his way.

However, the shoe fits; it is a beast to program in. Here, for instance, is a Brainfuck program that prints “helloworld”—and good luck making any sense of it: ++++++[−>+++++<]>−[>[++++>]++++[<]>−]>>>>.>+.<<…<−.<+++.>.+++.>.>>−. The upside of Brainfuck is its utter minimalism. It’s not quite a single-instruction language, like SUBLEQ, but as you can see, it includes only a handful of operations. Like a Turing Machine, it specifies a read/write head that can step left (the “<” instruction) or right (the “>” instruction) along a tape. The “+” and “−” instructions increment and decrement the byte at the current position on the tape. 33 The “,” and “.” instructions input a byte from the console, or output a byte to it (you can count ten “.” instructions in the code above, one to print each letter of “helloworld”). Finally, the “[” and “]” instructions implement looping: “[” will skip forward to its matching “]” if the byte at the current position is zero, and “]” will jump back to its matching “[” if the byte is nonzero. That’s it!

It’s hard to believe that Brainfuck could be used to fully implement, say, the Windows operating system, but it is “Turing complete.” Here that means: given enough time and memory (that is, a long enough tape), it can emulate any other computer and compute anything that can be computed.

In our version, which we call bff, there’s a “soup” containing thousands of tapes, each of which includes both code and data. This is key: in “classic” Brainfuck, the code is separate from the tape, whereas in bff, we wanted the code to be able to modify itself. That can only happen if the code itself is on the tape, as Turing originally envisioned.

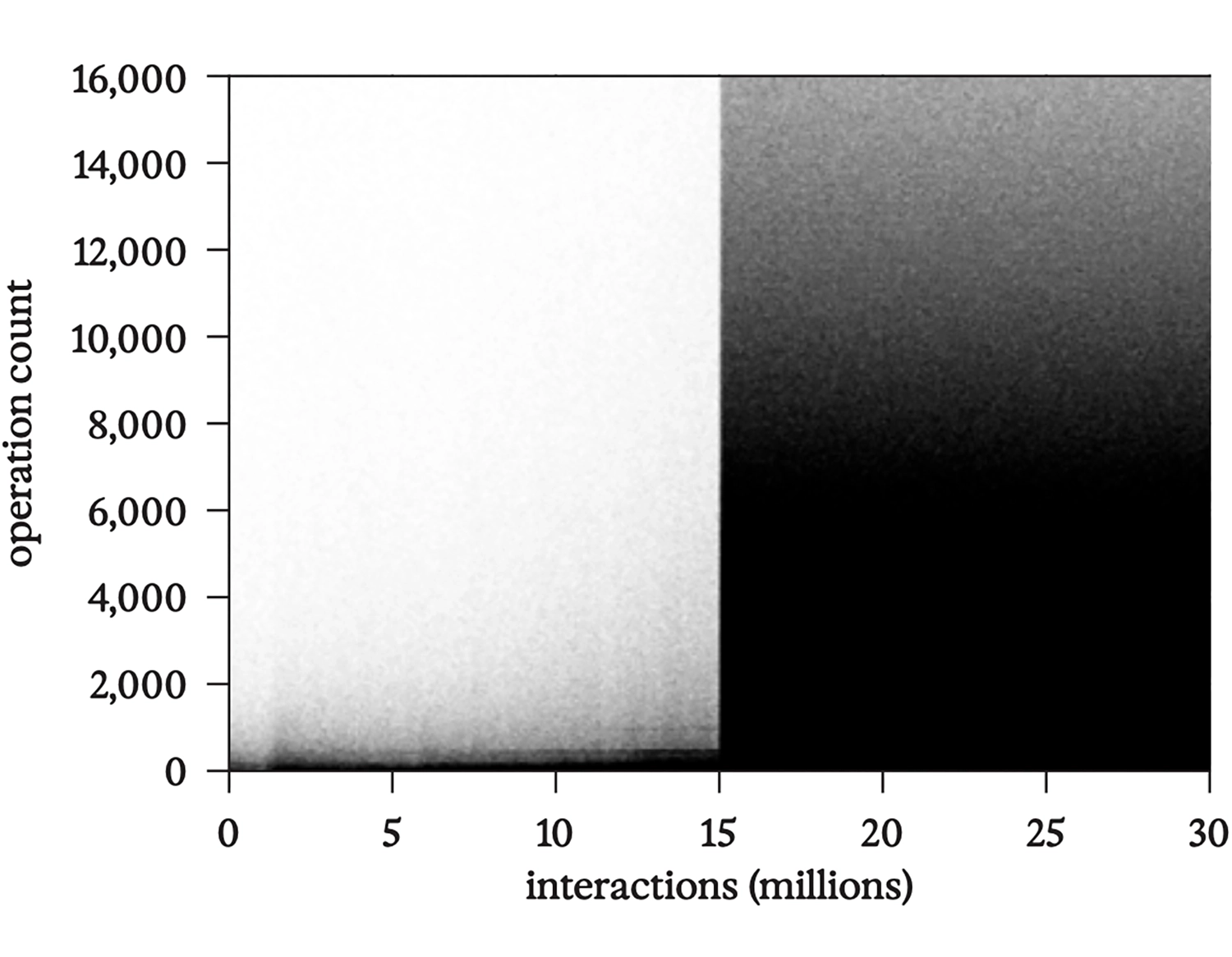

Bff tapes are of fixed length—64 bytes, about the same length as the cryptic “helloworld” program above. They start off filled with random bytes. Then, they interact at random, over and over. In an interaction, two randomly selected tapes are stuck end to end, and this combined 128 byte–long tape is run, potentially modifying itself. The 64 byte–long halves are then pulled back apart and returned to the soup. Once in a while, a byte value is randomized, as cosmic rays do to DNA.

Since bff has only seven instructions (represented by the characters “<>+−,[]”) and there are 256 possible byte values, following random initialization only 7/256, or 2.7 percent, of the bytes in a given tape will contain valid instructions; any non-instructions are simply skipped over. 34 Thus, at first, not much comes of interactions between tapes. Once in a while, a valid instruction will modify a byte, and this modification will persist in the soup. On average, though, only a couple of computational operations take place per interaction, and usually, they have no effect. In other words, while any kind of computation is theoretically possible in this toy universe, precious little actually takes place—at first. Random mutation may alter a byte here and there. Even when a valid instruction causes a byte to change, though, the alteration is arbitrary and purposeless.

But after millions of interactions, something magical happens: the tapes begin to reproduce! As they spawn copies of themselves and each other, randomness gives way to intricate order. The suddenness of this change resembles a “phase transition” in matter, as between gas and liquid, or liquid and solid. Indeed, the initial disorder of the soup is very much like that of randomly whizzing gas molecules. Hence random, non-functional code has been called “Turing gas”; 35 however, in bff, it “condenses” into functioning code, which is something far more complex than a solid or a liquid.

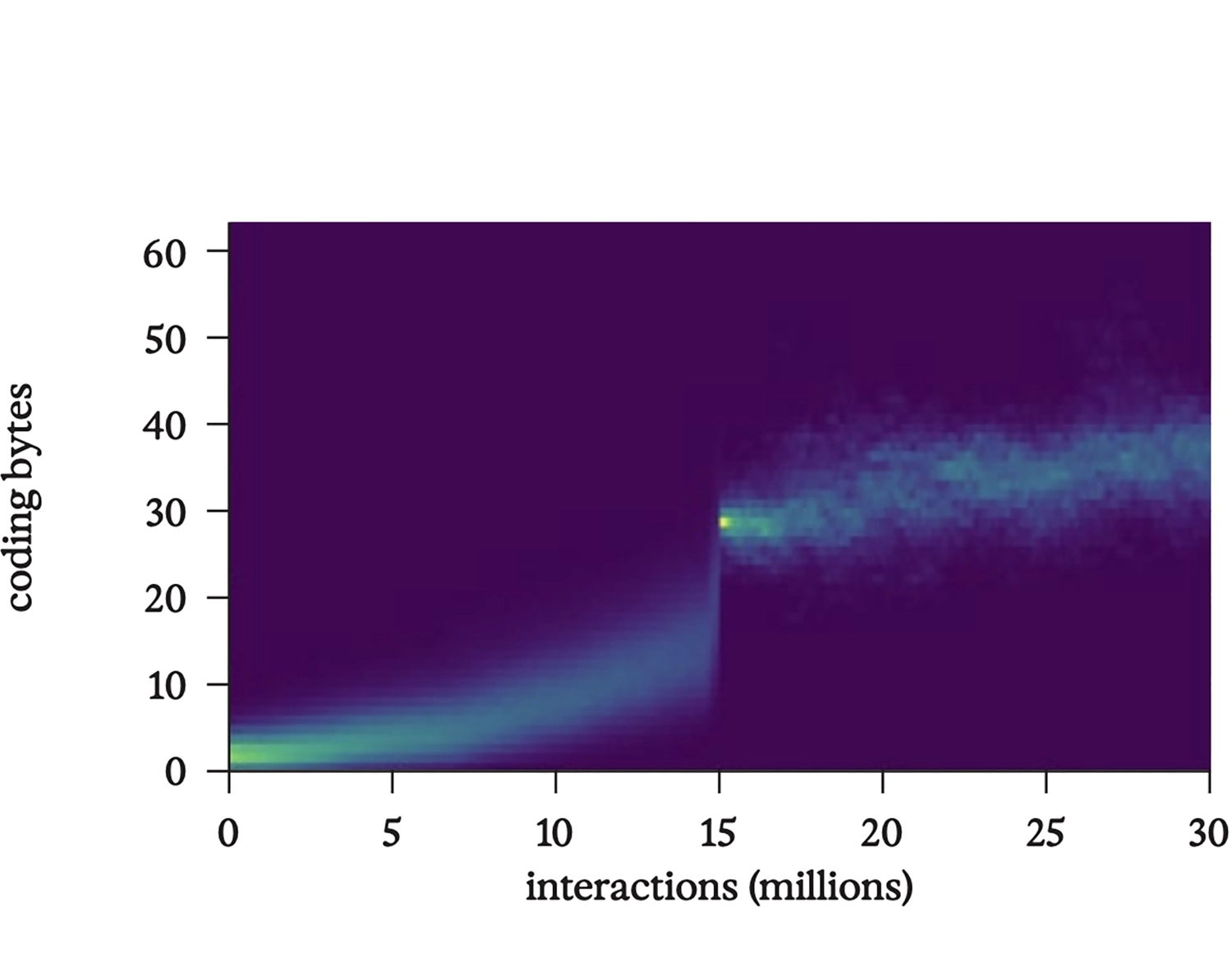

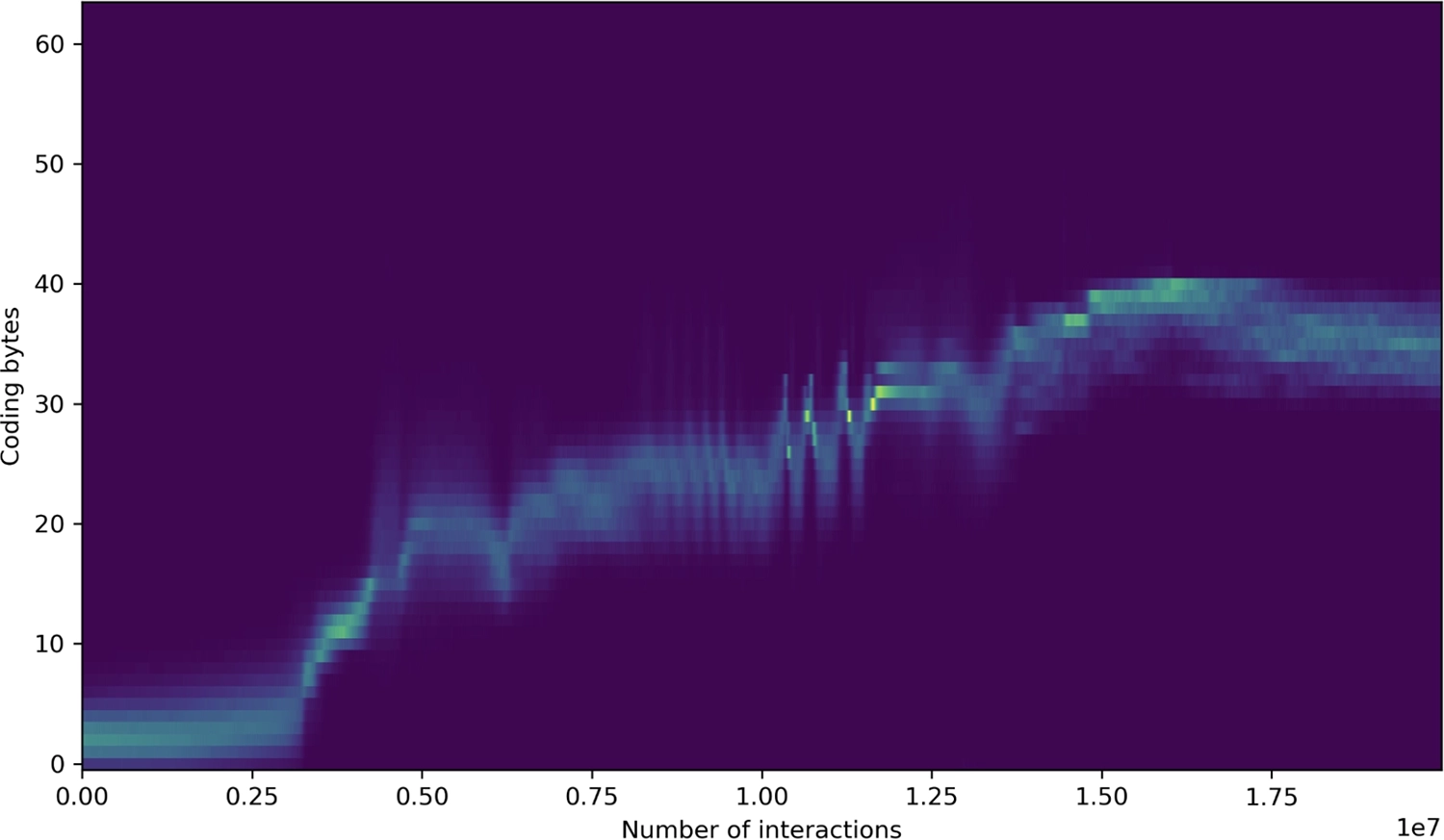

An early run of bff showing evolution from random initialization to full-tape replication; only bytes coding for instructions are shown.

We could call it “computronium,” 36 since when the phase transition occurs, the amount of computation taking place skyrockets—remember, reproduction requires computation. Two of Brainfuck’s seven instructions (“[” and “]”) are dedicated to conditional branching, and define loops in the code. Reproduction requires at least one such loop (“copy bytes until done”), causing the number of instructions executed in an interaction to climb into the thousands.

Scatter plot showing the first thirty million interactions in a bff run as dots with height equal to the number of operations. Note the sharp transition to computing-intensive full-tape replication at fifteen million interactions.

Histogram showing number of bytes coding for instructions per tape in the same bff run; note the ongoing rise in the amount of code even after the transition to full-tape replication at fifteen million interactions.

The code is no longer random, but obviously purposive, in the sense that its function can be analyzed and reverse-engineered. An unlucky mutation can break it, rendering it unable to reproduce. Over time, the code evolves clever strategies to increase its robustness to such damage.

This emergence of function and purpose is just like what we see in organic life at every scale; so we can talk about the function of the circulatory system, a kidney, or a mitochondrion, and how they can “fail”—even though nobody designed these systems.

We reproduced our basic result with a variety of other programming languages and environments. Alex (of neural cellular automata renown) created another beautiful mashup, this time between cellular automata and bff. Each of a 200×200 array of “pixels” contains a program tape, and interactions occur only between neighboring tapes on the grid. In a nod to our nerdy childhoods, the tapes are interpreted as instructions for the iconic Zilog Z80 microprocessor, launched in 1976 and used in many 8-bit computers over the years (including the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, Osborne 1, and TRS-80). Here, too, complex replicators soon emerge from random interactions, evolving and spreading across the grid in successive waves.

Evolution of competing replicators on a 200×200 grid of simulated Zilog Z80 processors

Our simulations suggest that, in general, life arises spontaneously whenever conditions permit. Those conditions seem minimal: little more than an environment capable of supporting computation, some randomness, and enough time.

Let’s pause and take stock of why this is so remarkable.

On an intuitive level, one does not expect function or purposiveness to emerge spontaneously. To be sure, we’ve known for a long time that a modest degree of order can emerge from initially random conditions; for instance, the lapping of waves can approximately sort the sand on a beach, creating a gradient from fine to coarse. But if we were to begin with sand on a beach subject to random wave action, and came back after a few hours to find a poem written there, or the sand grains fused into a complex electronic circuit, we would assume someone was messing with us.

The extreme improbability of complex order arising spontaneously is generally understood to follow from thermodynamics, the branch of physics concerned with the statistical behavior of matter subject to random thermal fluctuations—that is, of all matter, since above absolute zero, everything is subject to such randomness. Matter subject to random forces is supposed to become more random, not less. Yet by growing, reproducing, evolving, and indeed by existing at all, life seems to violate this principle.

The violation is only apparent, for life requires an input of free energy, allowing the forces of entropy to be kept at bay. Still, the seemingly spontaneous emergence and “complexification” of living systems has appeared to be, if not strictly disallowed by physical laws, at least unexplained by them. That’s why the great physicist Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961) wrote, in an influential little book he published in 1944 entitled What Is Life?,

[L]iving matter, while not eluding the “laws of physics” as established up to date, is likely to involve “other laws of physics” hitherto unknown, which, however, once they have been revealed, will form just as integral a part of this science as the former. 37

Thermodynamics

Before turning to those “other laws of physics,” it’s helpful to take a closer look at the original ones, and especially the Second Law of thermodynamics.

These are deep waters. While the fundamental ideas date back to the groundbreaking work of nineteenth-century mathematical physicist Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906), we can understand their essence without math. Nonetheless, Boltzmann’s conceptually challenging ideas flummoxed many of his fellow scientists, and the implications of his work continue to stir controversy even today. Much has been made of Einstein turning our everyday notions of space and time inside-out with his theory of relativity, developed in its initial form in 1905—just a year before Boltzmann, struggling with bipolar disorder, ended his own life. Arguably, though, Boltzmann’s earlier ideas disrupt our intuitions about time, cause, and effect even more radically than Einstein’s theory of relativity. 38 Let’s dive in.

Rusted and pitted struts of the partially collapsed seventy-year-old Nandu River Iron Bridge, Hainan Province, China

The Second Law of thermodynamics holds that any closed system will rise in entropy over time, becoming increasingly disordered. A hand-powered lawn mower, for example, starts off as a beautifully polished machine with sharp helical blades, round wheels, and toothed gears, all coupled together on smoothly rotating bearings. If left out in the elements, the bearings will seize up, the blades will dull, and oxidation will set in. After enough time, only a heap of rust will remain.

Similarly, if you were to take a dead bacterium (which, though a lot smaller, is far more complicated than a push mower) and drop it into a beaker of water, its cell membrane would eventually degrade, its various parts would spill out, and after a while only simple molecules would remain, dispersed uniformly throughout the beaker.

The Second Law gives time its arrow, because the fundamental laws of physics in our universe are very nearly time-reversible. 39 Strange, but true: Newton’s equations (classical dynamics), Maxwell’s equations (electromagnetism), Schrödinger’s equations (quantum physics), Einstein’s equations (special and general relativity)—all of these physical laws would work the same way if time ran in reverse. The difference between past and future evaporates when we look only at the mathematics of dynamical laws, or only at an individual microscopic event in the universe. The distinction between past and future, or cause and effect, only comes into view when we zoom out from that microscopic world of individual events and consider instead their statistics.

Here’s a common undergraduate thought experiment to illustrate this point in the case of Newtonian dynamics. Imagine video footage of balls on a billiard table, all in random positions and moving in random directions. They will collide with one another and with the bumpers at the edge of the table, bouncing off at new angles. If we (unrealistically) assume frictionless motion and fully elastic collisions (i.e., balls don’t slow down as they roll, and none of the collision energy is dissipated as heat), this would go on forever. The summed momenta and summed energies of the balls will remain constant—and it will be impossible to tell whether you’re watching the video forward or in reverse. In such a universe, causality has no meaning, because nothing distinguishes causes from effects.

If the initial conditions were random, then the positions of the balls will continue to be randomly distributed over the table’s surface as they all bounce around, transferring some of their energy to each other with every collision. It would be astronomically unlikely for the balls to all bunch up in one spot. Their velocities, too, will be randomly distributed, both in direction and magnitude, so it would also be astronomically unlikely for them to, for instance, suddenly all be moving precisely parallel to the table’s edges. Complete disorder, in other words, is a stable equilibrium. 40 In the presence of any thermal noise (that is, random perturbation), it is the only stable equilibrium.

Suppose, though, that the near-impossible happens. You see fifteen of the balls converge into a perfect, stock-still triangular grid, each ball just touching its neighbors, while the cue ball, having absorbed all of the combined kinetic energy of the other fifteen, whizzes away from the triangle. Aha! Now, we know that we’re watching a pool break—and we know that we’re watching it in reverse. The arrow of time has been established. Along with it, we have causation: the triangle broke because it was hit by the cue ball.

Billiard balls in motion: forward or backward in time?

Theoretically, nothing prevents the exact series of collisions from happening that would result in all of the energy being transferred to a single ball while leaving the others arrayed in a perfect triangle; but statistically, it’s vanishingly unlikely for such an ordered state to arise out of disorder—unless, perhaps, some mastermind set the balls in motion just so.

Although key thermodynamic concepts were not developed until the nineteenth century, an Enlightenment-era belief in a God who set the universe in motion just so arises intuitively from the apparent impossibility of order arising spontaneously out of disorder. 41 In a mechanical, billiard-table universe where the laws of physics are inviolable and the laws of statistics seem to inexorably degrade any pre-existing order over time, it seems absurd that anything as complicated as life could arise spontaneously without some supernatural agent acting as “prime mover.” Only a God with exquisite foresight could have “initialized” the Big Bang such that, in the Earth’s oceans billions of years ago, simple organic molecules floating around apparently at random could coalesce into a working bacterium—an improbability many, many orders of magnitude less likely than fifteen out of sixteen whizzing billiard balls spontaneously coalescing into an unmoving triangle.

The billiard ball universe I’ve just described may seem abstract or arbitrary, but nineteenth-century theorists like Boltzmann had become interested in this problem for the most practical of reasons: it was the physics behind steam power, hence the entire Industrial Revolution. 42 Engineering had preceded theory, as it often does.

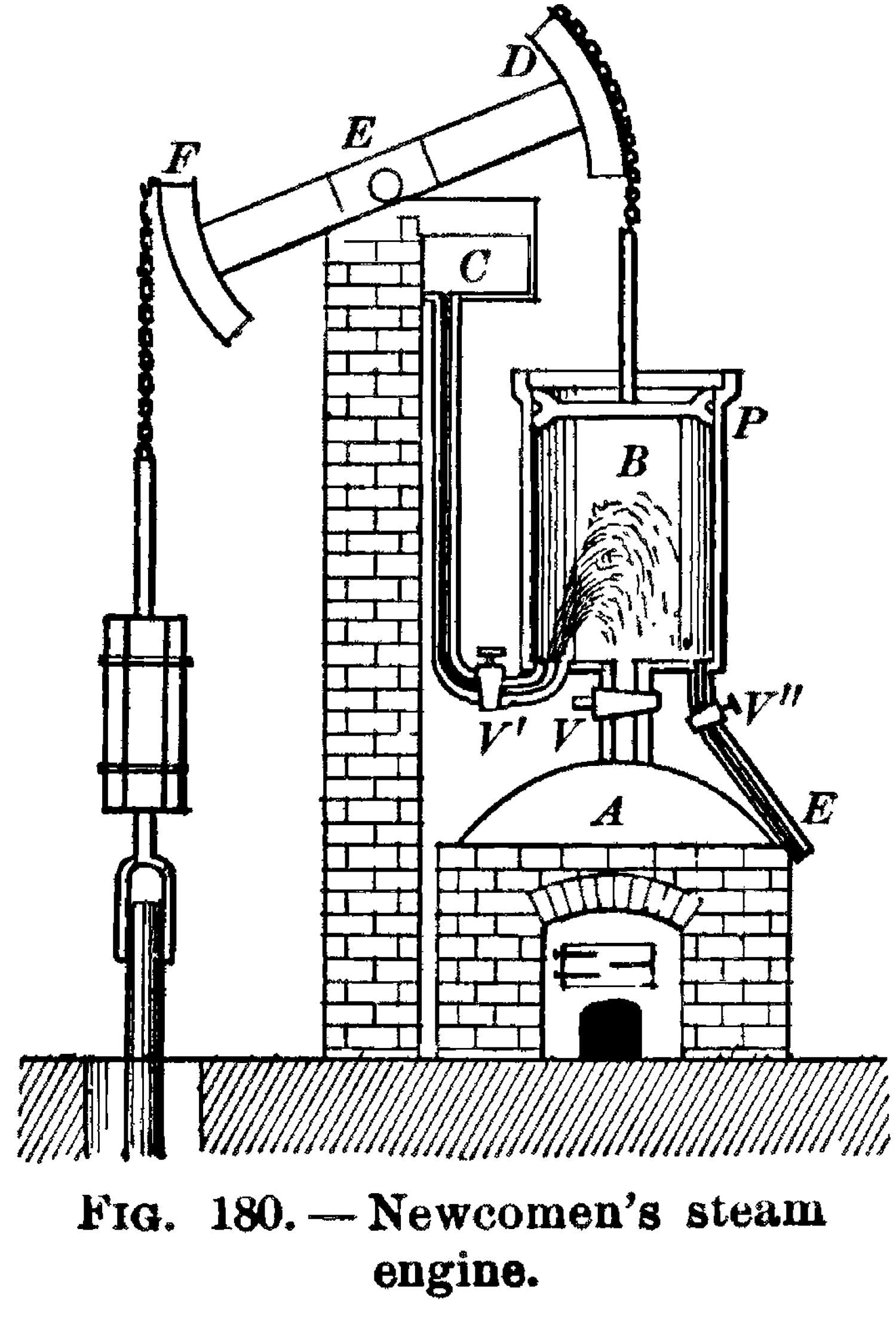

Thomas Newcomen (1664–1729), an English inventor and Baptist lay preacher, devised the first practical fuel-burning engine in 1712. It was based on a heating-and-cooling cycle. First, steam from a boiler was allowed to flow into a cylindrical chamber, raising a piston; then, the steam valve closed, and a second valve opened, injecting a jet of cold water, causing the steam to condense and pull the piston back down. As the piston rose and fell, it rocked a giant beam back and forth, which, in Newcomen’s original design, was used to pump water out of flooded mines (which, in turn, supplied the coal these engines would soon be consuming so voraciously).

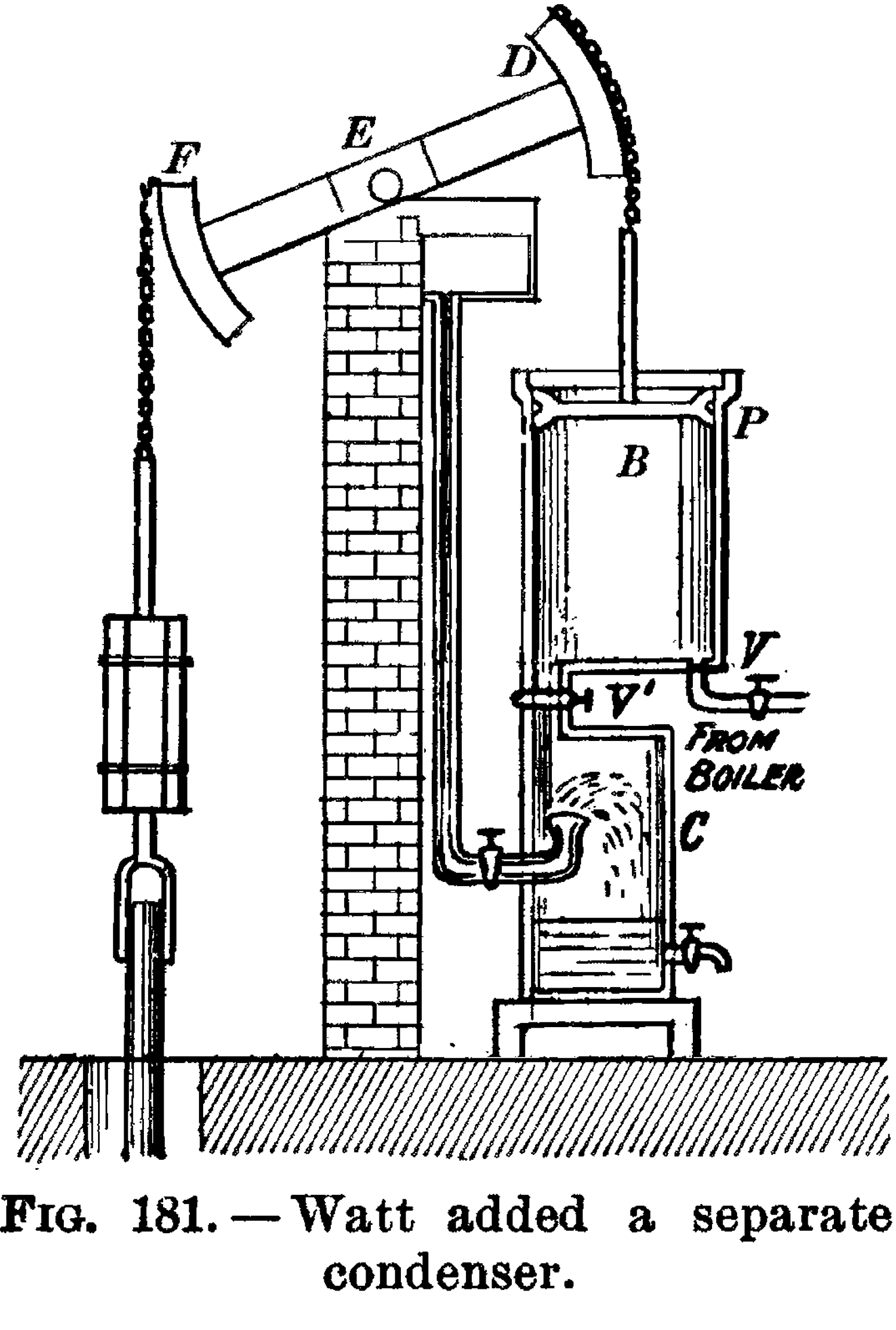

Scottish inventor and entrepreneur James Watt (1736–1819) greatly improved the steam-engine design in 1776, making it a practical replacement for human and animal power across a wide range of applications. This was when the Industrial Revolution really got underway; for the first time, human-made machines began to metabolize on a large scale, “eating” complex organic molecules to perform mechanical work.

Newcomen’s steam engine, from Black and Davis, Practical Physics, 1913

Watt’s steam engine, ibid.

Soon, far more energy would be flowing through this artificial metabolism than through the Krebs cycle in our own bodies. 43 It was, in the broad sense I’ve been using in this book, a major evolutionary transition: a symbiogenetic event between humans and machines, like earlier symbioses between humans and draft animals. Machine metabolism allowed human society to explode from its pre-industrial scale (about one billion people in 1800, most of whom lived in extreme poverty) to its scale today (eight billion, most of whom no longer live in poverty). 44 In the process, we’ve become nearly as dependent on machines for our continued existence as they are on us.

However, even as coal-powered engines transformed the Victorian landscape—both figuratively and literally, for the pollution was dire—nobody understood them at a deep level. What was heat, and how could it be converted into physical work? For a time, the leading theory held that heat was a kind of invisible, weightless fluid, “caloric,” that could flow spookily into and through other matter.

By combining Newtonian physics, statistical calculations, and experimental tests, Boltzmann and his colleagues figured out what was really going on. Their conceptual setup was a three-dimensional version of the billiard table, in which the balls were gas molecules whizzing around in a pressurized chamber, bouncing off its walls. Calculating the average effect of all the bouncing led to the Ideal Gas Law, which established theoretical relationships between the pressure, volume, and temperature of a gas. The theory closely matched observations by experimentalists and engineers. 45

Volume is straightforward (that’s just the size of the chamber), but the idea that pressure is the aggregate force on the chamber’s walls as molecules bounce off them, and that temperature is the average kinetic energy 46 of those whizzing molecules, was a profound insight. There was no need for any mysterious “caloric” fluid; heat was just motion on a microscopic scale. And the tendency toward a random distribution of molecular positions and momenta explains why, if you open a valve between two chambers containing gas at different pressures and/or temperatures, those pressures and temperatures will quickly equalize.

Before moving beyond classical thermodynamics, let’s add a bit more realism to our billiard-ball universe. We know that balls bouncing around a billiard table don’t actually go on bouncing forever. They encounter friction, slowing down as they roll. And when they bounce off each other, the collisions are slightly “inelastic,” meaning that after the collision, they’re moving a bit slower than before. After a little while, they stop rolling.

How can that be? At a microscopic level, the laws of physics are reversible. Momentum is supposed to be conserved. And the amount of matter and energy also remains constant, whether we run time forward or in reverse. That’s the First Law of thermodynamics!

Zooming in will reveal that, on a real billiard table, balls aren’t the smallest elements that bump against one other. Each billiard ball consists of lots of vibrating molecules bound together. Collisions between these individual molecules are what really cause the balls to bounce off each other—or, for that matter, cause a ball to roll across the felt rather than falling right through it. 47 In each case, momentum is transferred between molecules. Every time this happens, the distribution of molecular momenta becomes a bit more random, that is, a bit less correlated with which ball the molecule happens to be in, or indeed whether it is in a ball at all, or in the felt underneath.

In the most random distribution of molecular velocities, there would be no more correlation between the velocities of two molecules in one ball than in the velocities of molecules in different balls. Every ball would be imperceptibly jiggling in place, with each of its constituent molecules contributing minutely to the dance. We call that random jiggling “heat.” When all correlated motion has been converted into uniformly distributed heat, we’ve reached a stable equilibrium.

While the balls are still rolling, the correlations between the velocities of their molecules are by no means all equal; the distribution is far from random. This is not a stable equilibrium. Hence, the inevitability of friction and the inelasticity of collisions are statistical phenomena—just more symptoms of the inexorable Second Law.

Going forward, then, let’s imagine once more that the billiard balls are indivisible particles, not bound collections of molecules. In that case, all collisions would have to be elastic, all motion frictionless, and disordered, randomly colliding balls would be the equilibrium.

Once a system has reached equilibrium, it will stay that way forever—an end state Lord Kelvin called “heat death.” 48 This seemingly trivial observation has some profound consequences. First, the arrow of time will lose its meaning; any two consecutive moments A, B could just as likely have been ordered B, A. Nothing, therefore, can be said to be a cause, versus an effect.

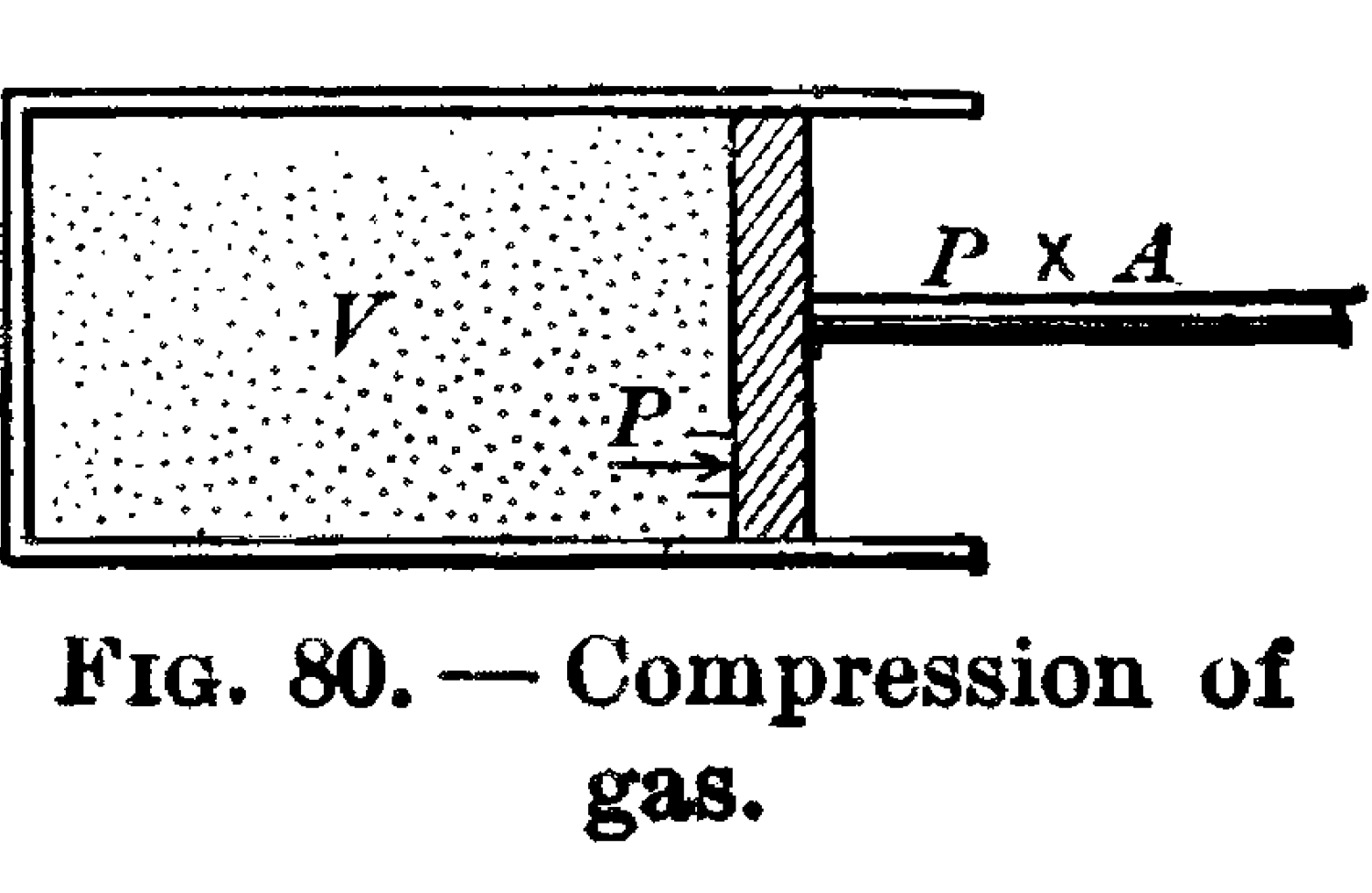

A piston with a face of area A and interior volume V containing an ideal gas at pressure P, ibid.

Relatedly, no work can be done. If the system were out of equilibrium—for instance, if all of the whizzing balls were on one side of the billiard table—then we could put a movable barrier down between the empty and occupied sides, attached to a loaded crankshaft. As they bounce around, the balls would then nudge the barrier, doing work. What I’ve just described is, of course, a piston, like that of a steam engine.

But if the balls were equally likely to be anywhere, then no matter how fast they whizz and bounce, there’s nowhere to put the barrier that would result in any net force. The piston wouldn’t move because it would be buffeted equally from all sides. This idea can be generalized: work can only be done by a system in disequilibrium, for instance, when the pressure or temperature is high in one place, and low in another. That’s why Newcomen’s engine needed both hot steam and cold water.

I’ve already used the term free energy, but now we can define it. The free energy of a system is the amount of work it can be made to do. Far from equilibrium, when the entropy is low, much of the kinetic energy in the billiard balls is “free”; it can be used to move pistons, raise weights, produce electric currents, carry out computations, or drive metabolic processes. But at equilibrium, the entropy is maximized, and the free energy is zero. This insight into the relationship between energy, entropy, and work lies at the heart of thermodynamics—and life.

Dynamic Stability

Recall that life seemed deeply weird to Schrödinger because living things appear to violate the Second Law. If the bacterium we drop into a beaker of water is alive rather than dead, and free energy is available in a form the bacterium can use, and the water contains simple molecules suitable for building more bacteria, then over time we will see the very opposite of an increase in disorder. After a while, the beaker will be full of bacteria, reproducing, cooperating, and competing with each other.

The bacteria will even be evolving. If the beaker is sufficiently large—the size of a planet, for instance—and we wait a few billion years, then eventually beings as complicated as us may be in there, along with cities, advanced technologies, and perhaps plans to colonize a nearby beaker.

None of these processes can occur without free energy. For us, it comes primarily from the sun. Thermodynamics tells us that even if the Second Law appears to be violated locally, it still holds when we zoom out. Order created in one place comes at the expense of increased disorder elsewhere. Hence, pollution, the finite lifetime of the sun, and the eventual heat death of the universe.

What concerns us here isn’t this big picture, but its apparent local violations, and the way they seem to become increasingly transgressive over time. The puzzle isn’t only that bacteria exist, but that as time passes, life on Earth seems to become more complex: from prokaryotes to eukaryotes; from eukaryotes to multicellular animals; from simple multicellular animals to ones with nervous systems; from brainy animals to complex societies; from horses and plows to space travel and AI.

Is there any general principle behind that complexification process, a kind of “however” or “yes, and” to the dismal Second Law? And could it account not only for evolution and complexification, but also for abiogenesis?

Yes, and yes. Bff can offer us a highly simplified model system for understanding that principle, just as an idealized billiard table gives us a model for understanding basic thermodynamics.

Replicators arise in bff because an entity that reproduces is more “dynamically stable” than one that doesn’t. In other words, if we start with one tape that can reproduce and one that can’t, then at some later time we’re likely to find many copies of the one that can reproduce, but we’re unlikely to find the other at all, because it will have been degraded by noise or overwritten.

Addy Pross, a professor emeritus of chemistry at Ben Gurion University of the Negev, describes the same phenomenon using the bulkier phrase “dynamic kinetic stability” (DKS). 49 I’ll drop “kinetic,” since the idea also applies far beyond Pross’s field of “chemical kinetics” (describing the rates at which chemical reactions take place). In bff, for example, dynamic stability can just as well apply to programs or program fragments.

As Pross points out, a population of replicating molecules can be more stable than even the hardiest of passive materials. A passive object may be fragile, like a soap bubble, or robust, like a stone sculpture. The sculpture might endure for longer, but, in the end, it’s still ephemeral. Every encounter it has with anything else in the world will cause its composition or structure to degrade, its individual identity to blur. For a sculpture, it’s all downhill. That’s the Second Law at work, as usual.

A self-reproducing molecule—like the DNA inside a living bacterium—is another matter. It is thermodynamically fragile, especially if we consider its identity to consist not only of a general structure but of a long sequence of specific nucleotides. However, its pattern is not just robust, but “antifragile.” 50 As long as DNA is able to reproduce—an inherently dynamic process—that pattern can last, essentially, forever. A bit of environmental stress or adversity can even help DNA maintain or improve its functionality. 51 This is how order overcomes disorder.

In fact, Darwinian selection is equivalent to the Second Law, once we expand our notion of stability to include populations of replicators. Through a thermodynamic lens, Darwin’s central observation was that a more effective replicator is more stable than a less effective one. As Pross puts it,

[M]atter […] tends to become transformed […] from less stable to more stable forms. […] [T]hat is what chemical kinetics and thermodynamics is all about […]. And what is the central law that governs such transformations? The Second Law. […] In both [the static and kinetic] worlds chemical systems tend to become transformed into more stable ones […]—thermodynamic stability in the “regular” chemical world, dynamic kinetic stability in the replicator world. 52

As a chemist, Pross is sensitive to the close relationships between energy, entropy, and stability, whether static or dynamic. However, he does not explicitly make a connection to the theory of computing.

It now seems clear that by unifying thermodynamics with the theory of computation, we should be able to understand life as the predictable outcome of a statistical process, rather than regarding it uneasily as technically permitted, yet mysterious. Our artificial life experiments demonstrate that, when computation is possible, it will be a “dynamical attractor,” since replicating entities are more dynamically stable than non-replicating ones; and, as von Neumann showed, replicators are inherently computational.

Bff has no concept of energy, but in our universe, replicators require an energy source. This is because, in general, computation involves irreversible steps—otherwise known as causes and effects—and thus, computing consumes free energy. That’s why the chips in our computers draw power and generate heat when they run. (And why my computer heats up when it runs bff.) Life must draw power and generate heat for the same reason: it is inherently computational.

Complexification

When we pick a tape out of the bff soup after millions of interactions, once replicators have taken over, we often see a level of complexity in the program on that tape that seems unnecessarily—even implausibly—high. A working replicator could consist of just a handful of instructions in a single loop, requiring a couple of hundred operations to run. Instead, we often see instructions filling up a majority of the 64 bytes, multiple and complex nested loops, and thousands of operations per interaction.

Where did all this complexity come from? It certainly doesn’t look like the result of simple Darwinian selection operating on the random text generated by a proverbial million monkeys typing on a million typewriters. 53 In fact, such complexity emerges even with zero random mutation—that is, given only the initial randomness in the soup, which works out to fewer bytes than the text of this book. Hardly a million monkeys—and far too few random bytes to contain more than a few consecutive instructions, let alone a whole working program.

The answer recalls Lynn Margulis’s great insight: the central role of symbiosis in evolution, rather than random mutation and selection. When we look carefully at the quiescent period in the bff soup before tapes begin replicating, we notice a steady rise in the amount of computation taking place. We are observing the rapid emergence of imperfect replicators—very short bits of code that, in one way or another, have some nonzero probability of generating more code. Even if the code produced is not like the original, it’s still code, and only code can produce more code; non-code can’t produce anything!

Thus, a selection process, wherein code begets code, is at work from the very beginning. This inherently creative, self-catalyzing process is far more important than random mutation in generating novelty. When bits of proliferating code combine to form a replicator, it’s a symbiotic event: by working together, these bits of code generate more code than they could separately, and the code they generate will in turn produce more code that does the same, eventually leading to whole-tape replication and an exponential takeoff.

A closer look at the bff soup prior to the exponential takeoff reveals distinct phases of “pre-life,” which might have had close analogs during abiogenesis on Earth. In the first phase, individual instructions occasionally generate another individual instruction, but this is more akin to a simple chemical reaction than to any real computation; the instructions are not acting as part of any larger program.

In the second phase, we begin to see instructions in particular positions, or in particular combinations, that are likelier to lead to copies of themselves than one would expect by random chance, albeit often in indirect ways. “Autocatalytic sets” start to form: cycles of dynamical interactions that mutually reinforce each other. These, too, can arise spontaneously in the chemical world, and have long been theorized to have driven abiogenesis. 54

At this point, with autocatalytic fragments of code proliferating and colliding, a leap becomes possible that brings us beyond the world of digital chemistry and into the world of real computation: the emergence of the first true replicators. These are no longer mere autocatalytic sets, but short programs that copy themselves, or each other, using looped instructions.

With this leap to computation comes an enormous upgrade in evolvability, because now, any change made to a program that does not break its copy loop will be heritable. Thus, classical Darwinian selection can kick in, allowing adaptation to a changing environment or speciation for occupying diverse niches. If we insist on making a distinction between non-life and life, this might be a reasonable place to draw that line.

However, these earliest replicating programs are unlikely to cleanly copy a whole tape. Often, they only copy short stretches of tape, which may get pasted into arbitrary locations, yielding unpredictable results. As these scrappy, fragmentary replicators proliferate, the bff soup enters a chaotic phase. Despite the churn, the tapes have not, at this point, resolved into any obvious structure. To the naked eye, they still look like random junk, although the rising amount of computation taking place (as measured both by the average number of operations per interaction and the density of instructions per tape) suggests that something is afoot.

Tracking the provenance of every byte in the soup, starting from random initialization, can make sense of the apparent chaos. At first, almost every byte of every tape remains whatever it was at initialization time; if we draw a line from each byte’s current position on a tape to its original source position, the lines will all extend back to time zero in parallel, like the warp threads of a loom. Once in a while, a byte will change, cutting a thread, or get copied, pulling it across the other threads diagonally.

Provenance of individual bytes on tapes in a bff soup after 10,000, 500,000, 1.5 million, 2.5 million, 3.5 million, 6 million, 7 million, and 10 million interactions. The increasing role of self-modification in generating novelty is evident, culminating in the emergence (just before 6 million interactions) of a full-tape replicator whose parts are modified copies of a shorter imperfect replicator.

With the rise of scrappy replicating programs, all remaining dependencies on the past are quickly cut as replicators copy over each other in a frenzy of creative destruction. Any given byte might get copied hundreds of times to a series of different tape locations, in the process wiping out whatever had previously been there. Shortly afterward, all of those copies might get wiped out in turn by some other more efficiently replicating fragment. Soon, every byte’s history becomes very brief in time, yet complex in space—a short-lived snarl of sideways jumps. The loom becomes all weft, and no warp.

Are these scrappy replicators competing or cooperating? Both. Replicators that can’t keep up are wiped out, along with any non-replicating bytes. Surviving replicators, on the other hand, continually form chimeras, 55 recombining with other replicators (or even copies of themselves) to become more effective still. These are, once more, symbiogenetic events: sub-entities merging to form a larger, more capable super-entity.

This chaotic phase is such a potent crucible for directed evolution that it generally doesn’t last long. It rapidly produces a robust whole-tape replicator, which then takes off exponentially, resulting in the dramatic transition to the organized structures (and large amounts of computation) that are bff’s most obvious feature. At this point, artificial life seems to spontaneously emerge.

But as we can now appreciate, there’s nothing spontaneous about it. Replicators had been present all along, and each larger replicator is composed of smaller ones—an inverted tree of life, consisting of mergers over time rather than splits.

However, evolution’s creative work is not done yet. After the takeoff of a fully functional tape replicator, we often see yet further symbiotic events. From a classical Darwinian standpoint, this seems puzzling, since further evolution seems superfluous once whole tapes are replicating reliably. How could “fitness” possibly improve further, once a tape copies itself in its entirety every time it interacts with another tape?

We must consider that since the instructions for whole-tape replication don’t occupy all 64 bytes, there’s extra space on the tape that could be dedicated to … anything. That’s the point of von Neumann–style replication—it allows for open-ended evolution precisely because the tape can contain additional information, beyond the code needed for replication itself. 56

Any extra replicated bytes could, of course, be random—just passive, purposeless information cargo hitchhiking from one generation to the next. But if these bytes contain instructions, those instructions can run. And if they can run, they can replicate themselves, too. Thus, the symbiogenetic process can continue to operate, creating additional replicators within an already replicating tape. Sometimes these sub-replicators even produce multiple copies of themselves in a single interaction.

Sub-replicators can interact with their host in many ways. They can “kill” the host by damaging its replication code, which is generally catastrophic for the sub-replicator, as it thereby destroys the environment within which it can run. Sub-replicators can be neutral, leaving the host’s replication machinery alone. Or, they can be symbiotic, for instance by conferring resistance to mutational damage via redundant copying of the host’s code. The overall tendency is toward symbiosis, since that is the most dynamically stable.

Over time, code colonizes a large proportion of the 64 bytes. Code is more dynamically stable than non-code, and its dynamic stability increases through symbiosis with yet more code—in particular, when code fragments find ways to work in functional tandem.

Histogram showing how many of a tape’s 64 bytes code for instructions; note, as before, the ongoing rise after full-tape replication, which here begins at about 3 million interactions.

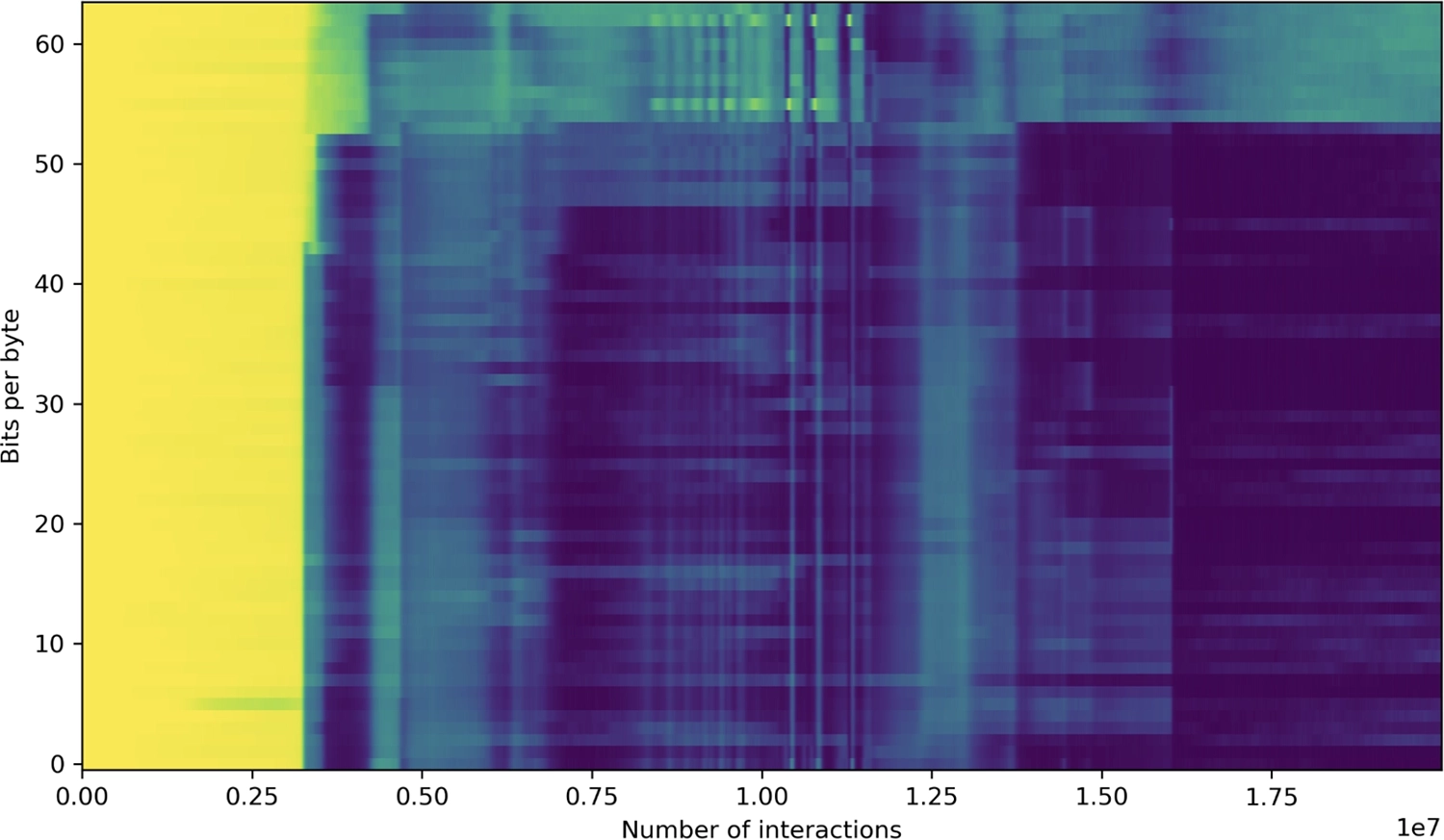

The variability or amount of information in a tape byte at each position, expressed as an entropy in bits. Prior to the transition, the value is close to 8 (corresponding to a random distribution over values 0–255), but at the time of transition to full-tape replication it drops dramatically; some positions are more variable than others, though, with higher variability toward the end of the tape.

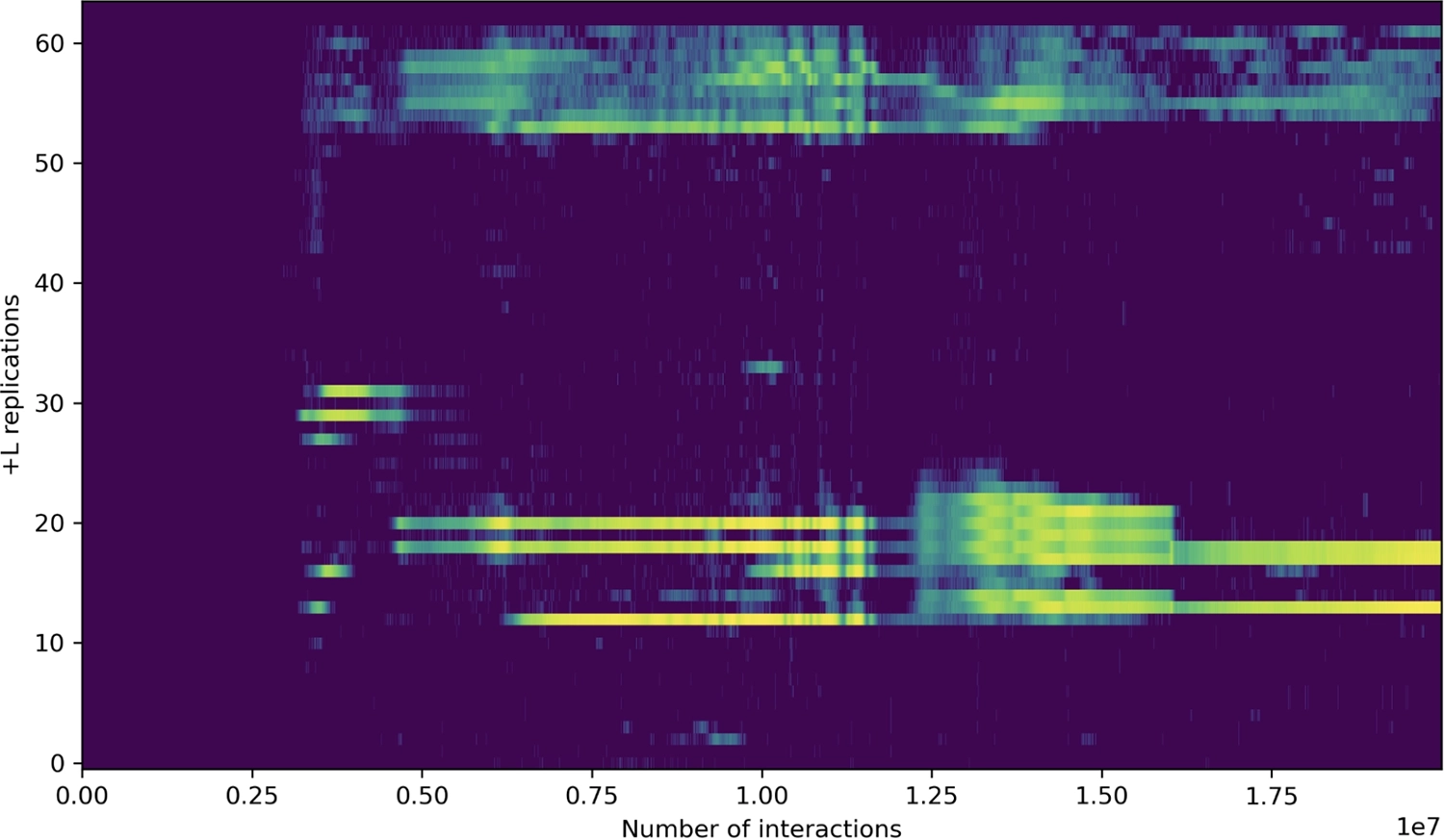

Histogram showing positions of “[” loop instructions that perform an “aligned” copy of a tape region on one tape to the same position on the other tape, corresponding to perfect replication. Note that there are multiple perfect replicators in the soup, with populations that change over time.

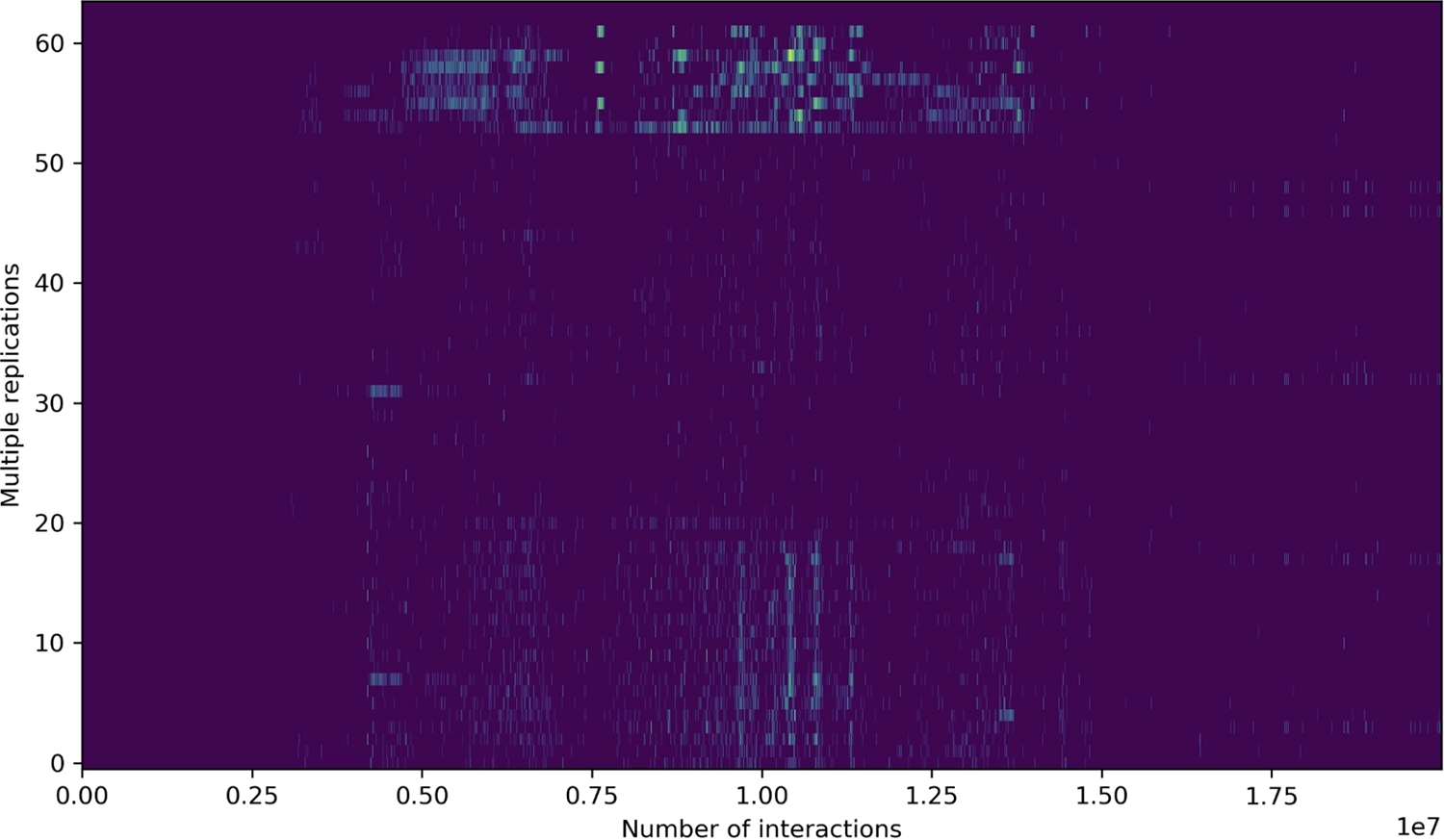

Histogram showing positions of “[” loop instructions that replicate themselves multiple times when run, shown emerging in this run after full-tape replication.

In a way, symbiosis is the very essence of functionality. When we talk about a kidney’s function only making sense in context, we mean that it is in symbiosis with other functions—like those of the liver (breaking ammonia down into urea), the heart (pumping blood), and so on. Each of these functions is purposive precisely because its inputs are the outputs of others, its outputs are inputs to others, and thus they form a network of dynamically stable cycles.

The same is true of larger, planetary-scale interrelationships. The “purpose” of plants, from the perspective of animal life, is to produce oxygen and sugar, which we breathe and eat. The “purpose” of animals, from a plant’s perspective, is to turn the oxygen back into carbon dioxide, and provide compost and pollination. Our growing understanding of life as a self-reinforcing dynamical process boils down not to things, but to networks of mutually beneficial relationships. At every scale, life is an ecology of functions.

Because functions can be expressed computationally, we could even say that life is code. Individual computational instructions are the irreducible quanta of life—the minimal replicating set of entities, however immaterial and abstract they may seem, that come together to form bigger, more stable, and more complex replicators, in ever-ascending symbiotic cascades.

In the toy universe of bff, the seven special characters “<>+−,[]” are the elementary instructions. On the primordial sea floor, geothermally-driven chemical reactions that could catalyze further chemical reactions likely played the same role. Under other conditions, on another planet, or in another universe, many different elementary interactions could do the same—as long as they are Turing complete, enabling them to make the leap from autocatalytic sets to true replication.

Compression

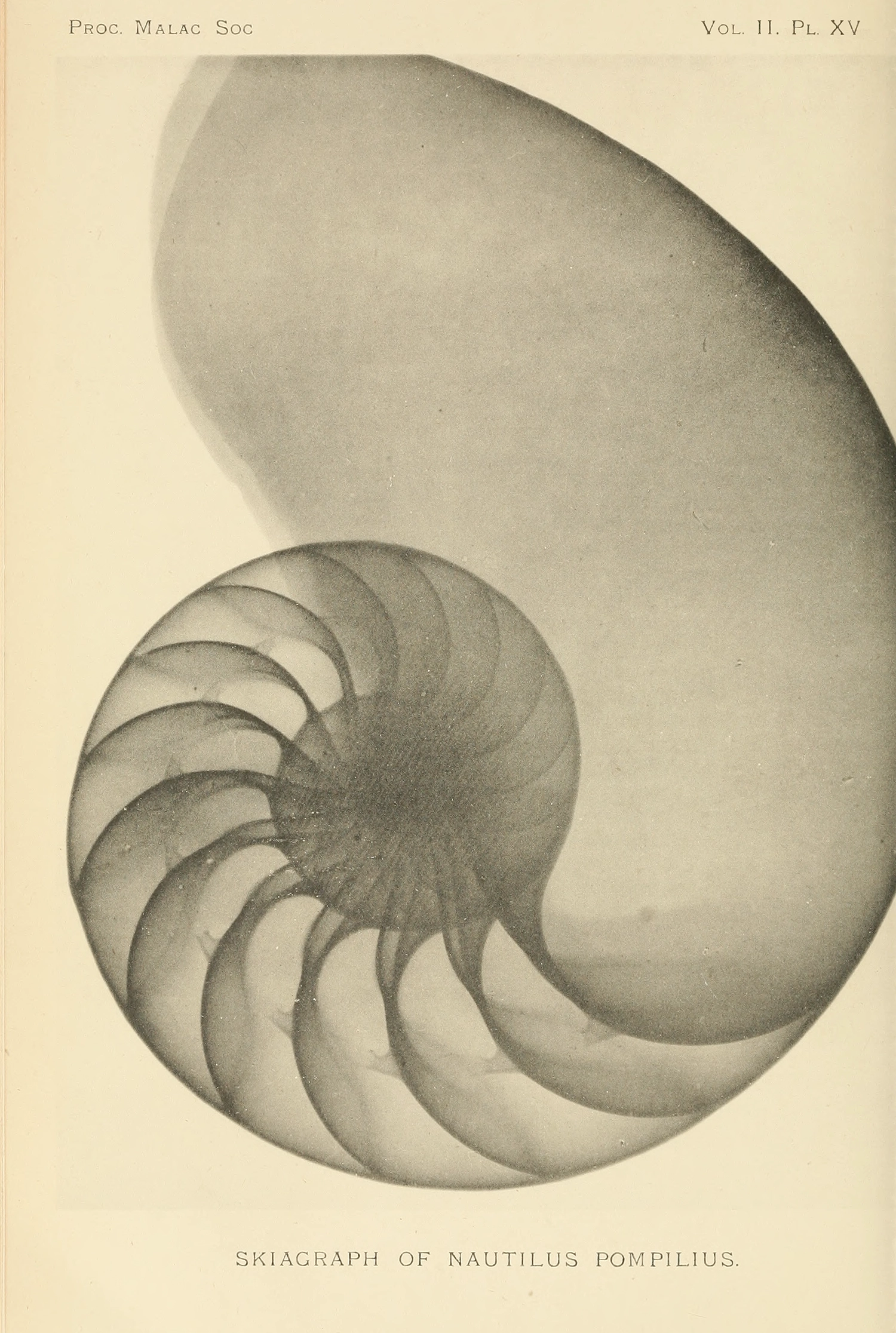

When code evolves through symbiogenesis, it will develop a curious statistical structure: parts of it will be copies (or near-copies) of other parts, and as those parts establish symbiosis, they’ll form a larger aggregate which will also copy itself as a unit. This is reminiscent of (though not the same as) a “fractal”: a structure that resembles itself at a cascade of ever-finer scales. Let’s take a short detour through fractals and their relationship to biology so that we can then consider the implications of evolution itself exhibiting certain fractal-like properties.

French-American mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot (1924–2010) is the figure most associated with fractals, though they were first described by English meteorologist Lewis Fry Richardson (1881–1953). In the aftermath of World War II, Richardson, a Quaker, had been trying to build a mathematical model to predict the likelihood of conflicts between countries. One of the parameters in his model was the length of their common border. He was perplexed to find, though, that certain borders didn’t appear to have agreed-upon lengths. The Portuguese, for instance, reported that their border with Spain was 613 miles long, but the Spanish claimed that it was 754 miles long. This seemed like a weirdly large discrepancy for what ought to have been an easily surveyed distance!

Richardson eventually figured out what was going on: the Spanish were using a higher-resolution map. Every twist and turn the Portuguese could see in the Minho, Douro, and Guadiana rivers separating the countries had finer-scale twists and turns only visible on the Spanish map. Richardson showed that, if zooming in on any given meandering revealed more meanderings, the total length of a “self-similar” curve like a coastline or a river can grow without limit as one measures it with an ever-smaller ruler. 73

The coast of Britain measured with rulers of different lengths

“Fractal geometry” is thus very different from the Euclidean geometry we all learned in school, where the length of a line or curve is well-defined and doesn’t blow up when you zoom in. Of course, in real life, one can’t zoom in forever, but fractals are still important mathematical tools for understanding structures that are self-similar over a range of scales, like rivers and coastlines.

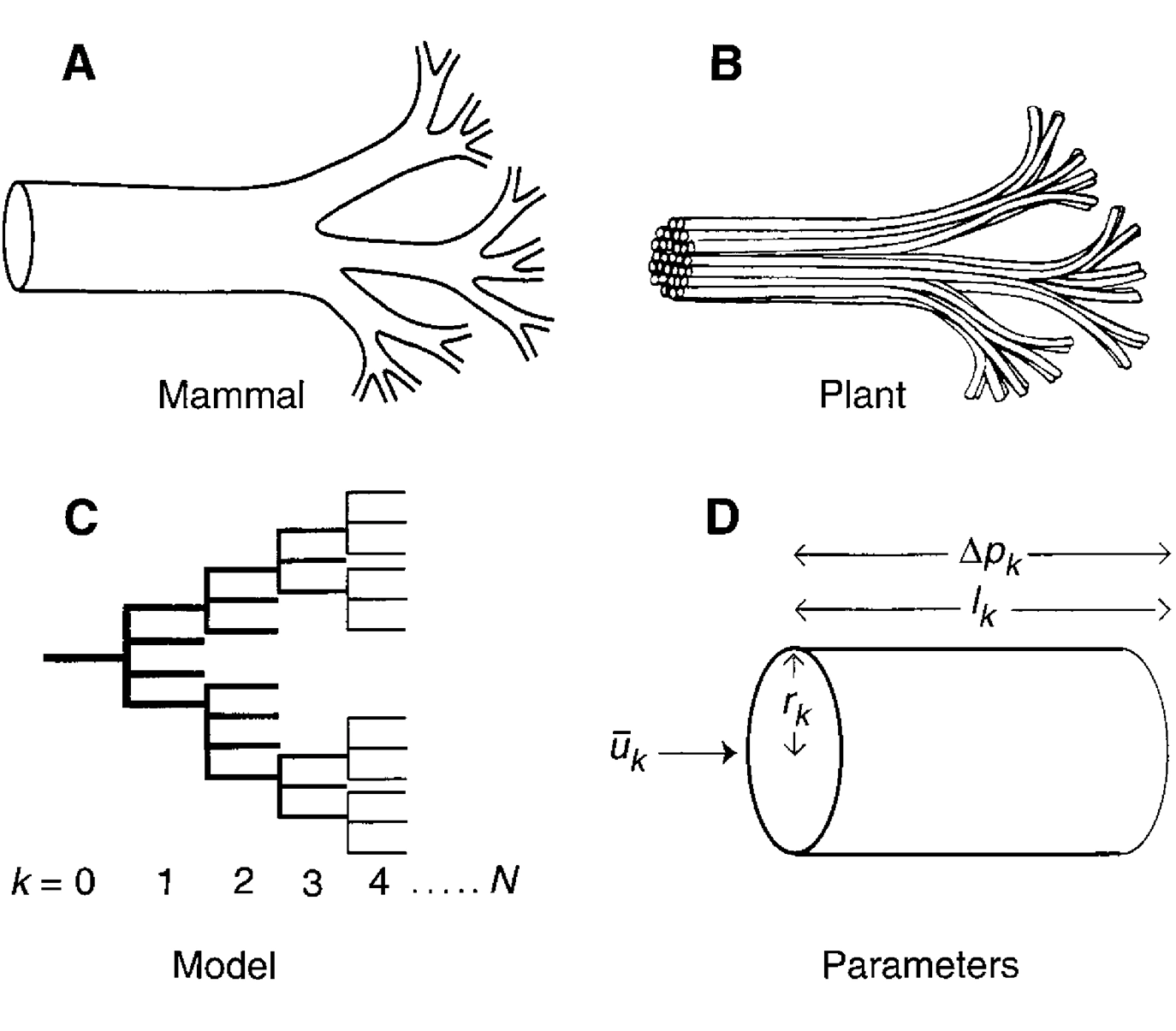

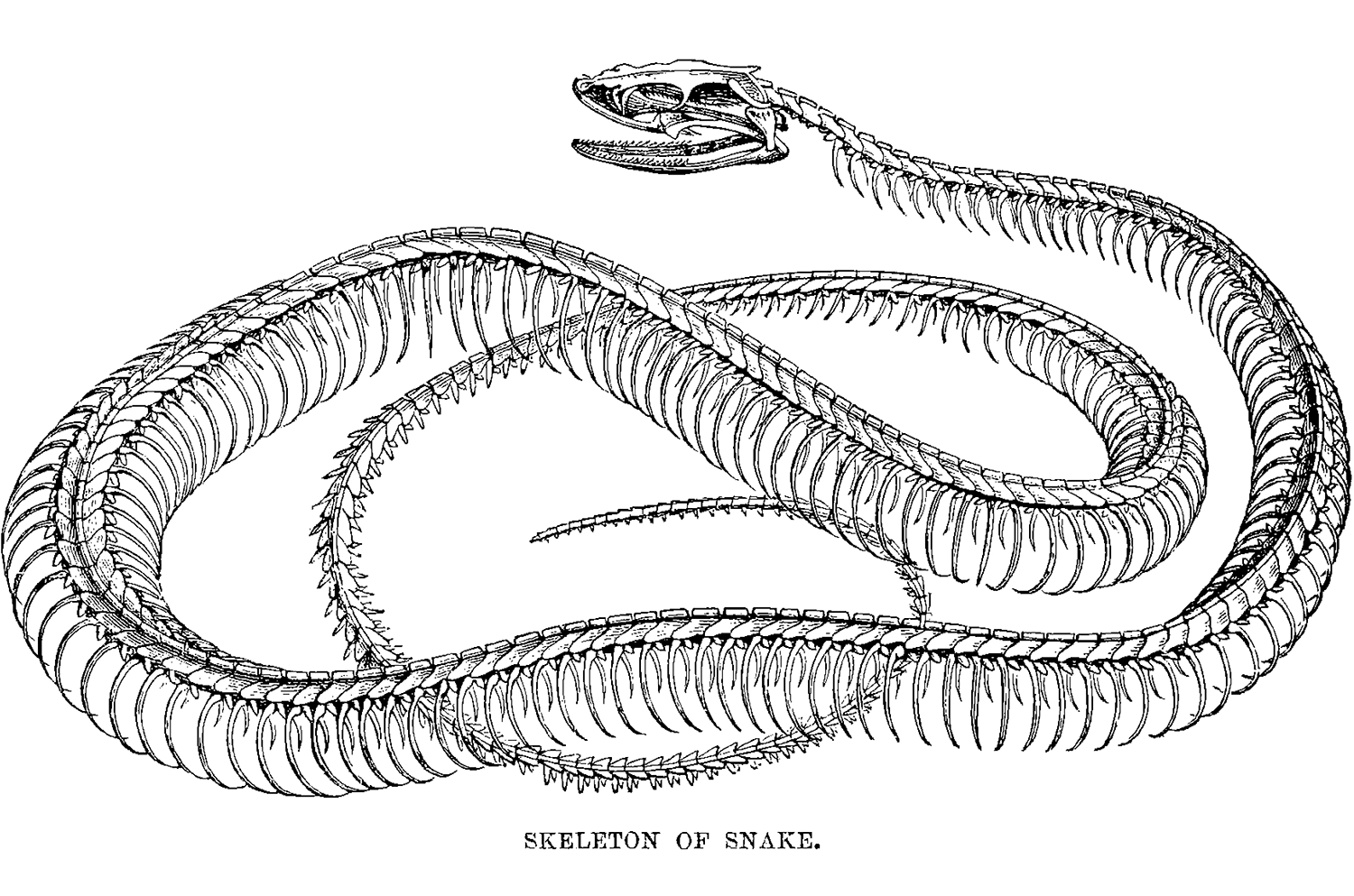

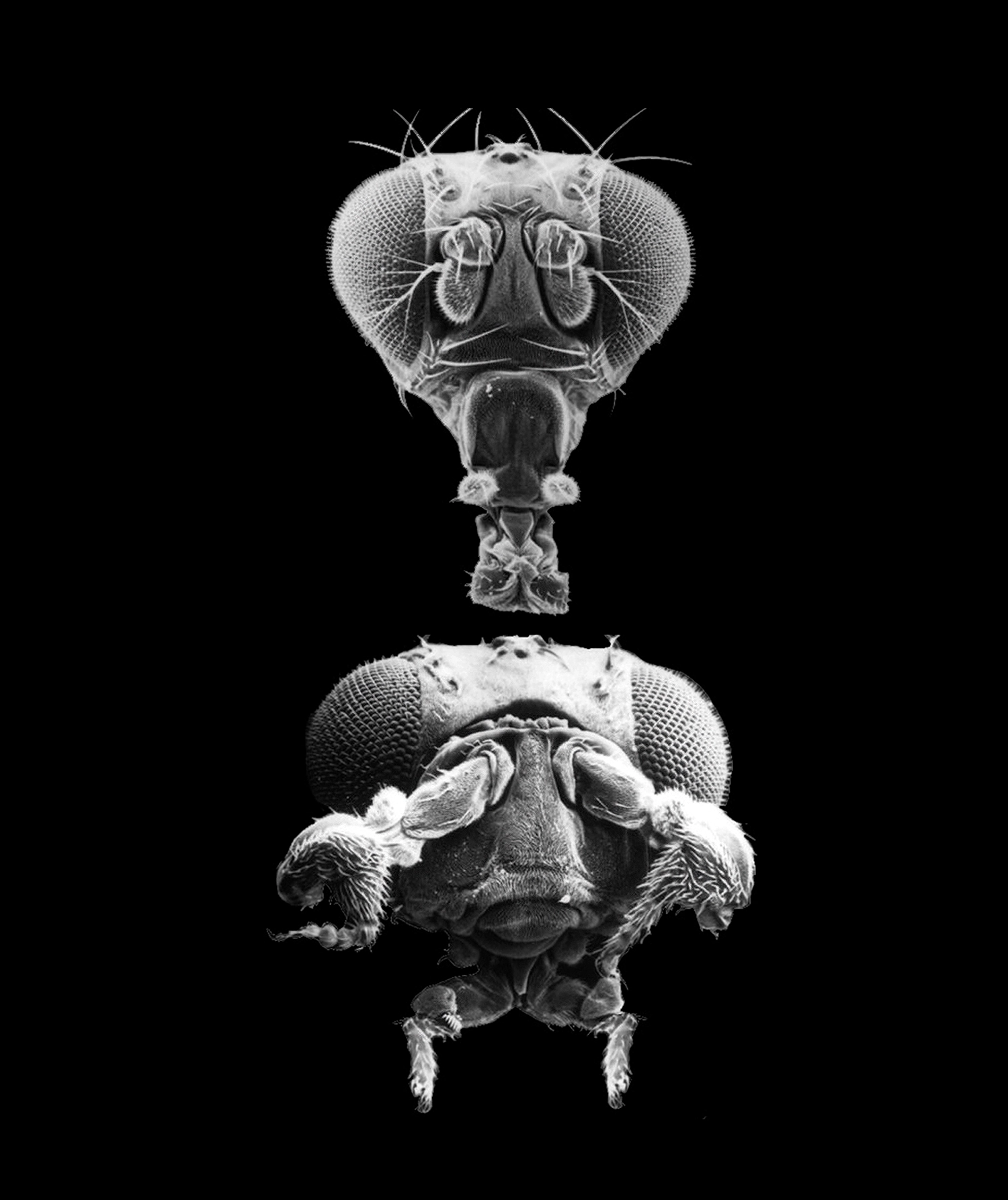

Living organisms exhibit obvious fractal properties in certain of their structures, such as tree branches, bronchial tubes, and circulatory systems. In structures like these, fractal geometry over some range of scales offers an elegant design solution to a biophysical problem. For instance, blood carrying oxygen and nutrients needs to reach every cell in the body, which means that oxygenated blood has to be pumped through a branching network of tubes, and these tubes—which are, in Euclidean terms, one-dimensional—have to repeatedly subdivide to “fill” three-dimensional space. Hence, we have fractally branching (and then merging) networks of arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins.